The American settlement was “little better than a field of guerrilla warfare, robbery and plunder,” complained mining promoter Charles Poston, after American filibusters terrorized the borderlands in 1857. “It results that we are in a state of anarchy,” he wrote on August 5, “and there is no government, no protection to life, property, or business ; no law and no self-respect or morality among the people. We are living in a perfect state of nature, without the restraining influence of civil or military law, or the amelioration of society. . . In the midst of all this, the Government has blessed us with a custom house at Calabazos to collect duties upon the necessaries of life . . . God send that we had been left alone with the Apaches. We should have been a thousand times better off in every respect.“ — Sylvester R. Mowry, Memoir of the Proposed Territory of Arizona (Washington, D.C.: Henry Polkinhorn, Printer, 1857), 22.

a frontier changes nations

When a State Department emissary secured the signatures of three Mexican diplomats to the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo in February 1848, ending the Mexican-American War, President James Polk responded with anger, rather than gratitude. Polk had recalled Nicholas Trist from the diplomatic mission, but the clerk had ignored his instructions and continued negotiations. Polk terminated his salary, leaving him stranded in Mexico. His marriage to Virginia Jefferson Randolph, a granddaughter of Thomas Jefferson, earned him little mercy: after dismissal from state service, he would wait twenty-two years for another appointment — as postmaster in Alexandria, Virginia. Initially the Senate Foreign Relations Committee recommended rejection of Trist’s treaty, due to bribery and other coercive tactics he had used to achieve it. But Polk forwarded the document to the full Senate for ratification, which it confirmed in March.

The president was annoyed by the chief clerk’s insubordination, and disappointed in the treaty’s failure to accommodate a railroad route or access to the Gulf of California, but he also understood it largely won the expansion he had sought: the Republic of Mexico would cede nearly six hundred thousand square miles of land — an area encompassing the entire future states of California, Nevada, and Utah, and parts of Wyoming, Colorado, New Mexico, and Arizona — and the United States would pay Mexico more than fifty-three million dollars for a range of indemnities and claims. The decision to sign may not have been difficult for the Mexican diplomats. Most of their nation’s largest cities, including the capital, were occupied by American troops, and they may have surmised Polk was listening to Secretary of State James Buchanan and others urging him to annex the entire country. Giving up nearly half their territory was better than losing it all.

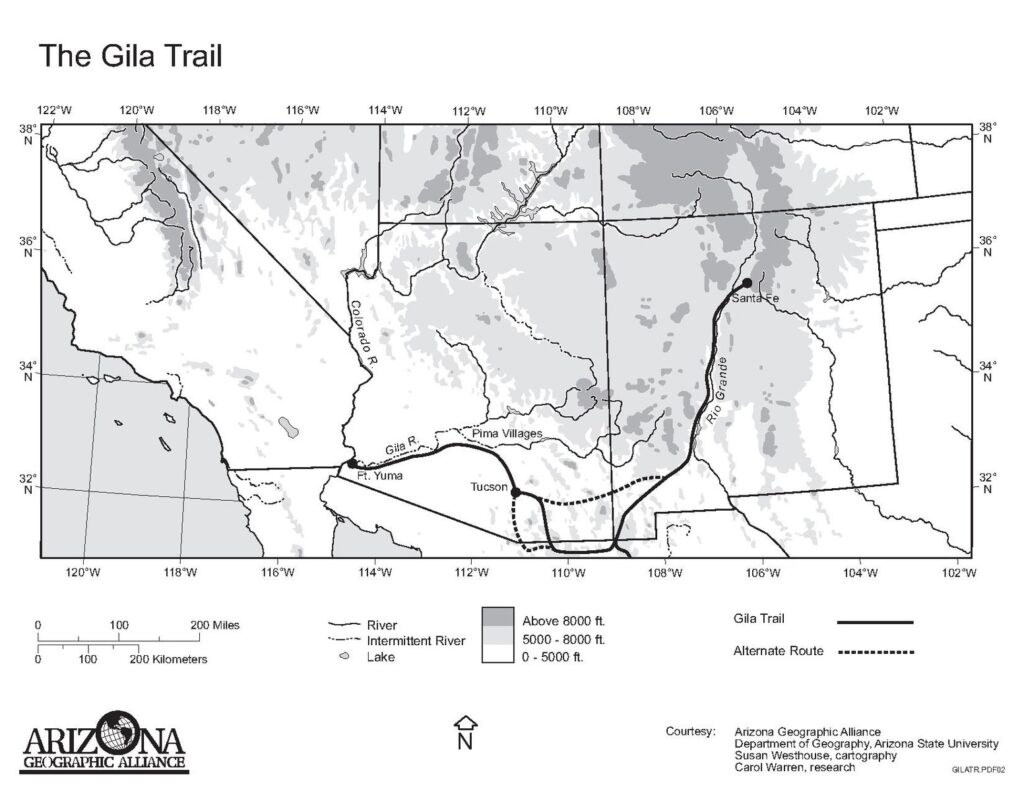

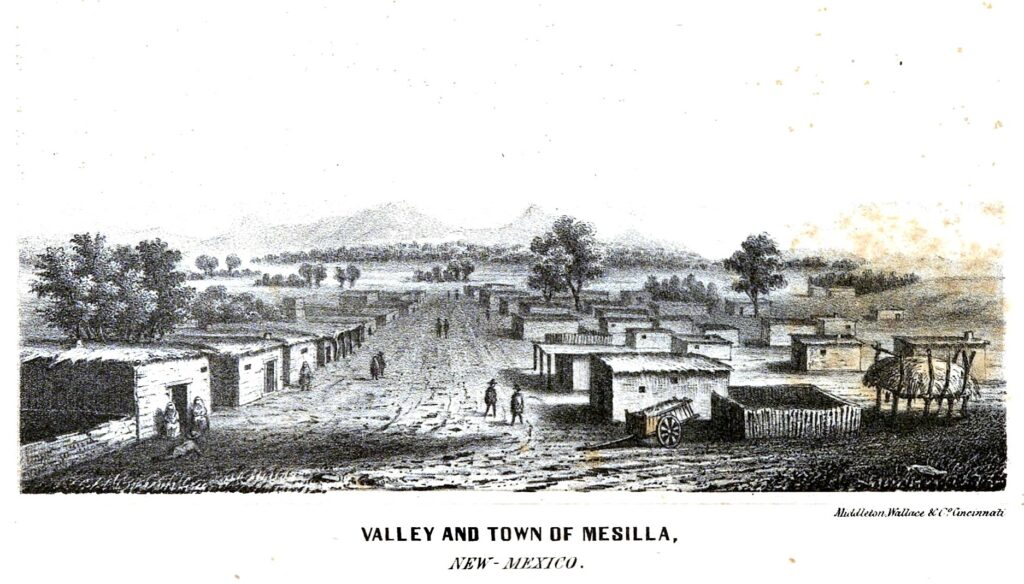

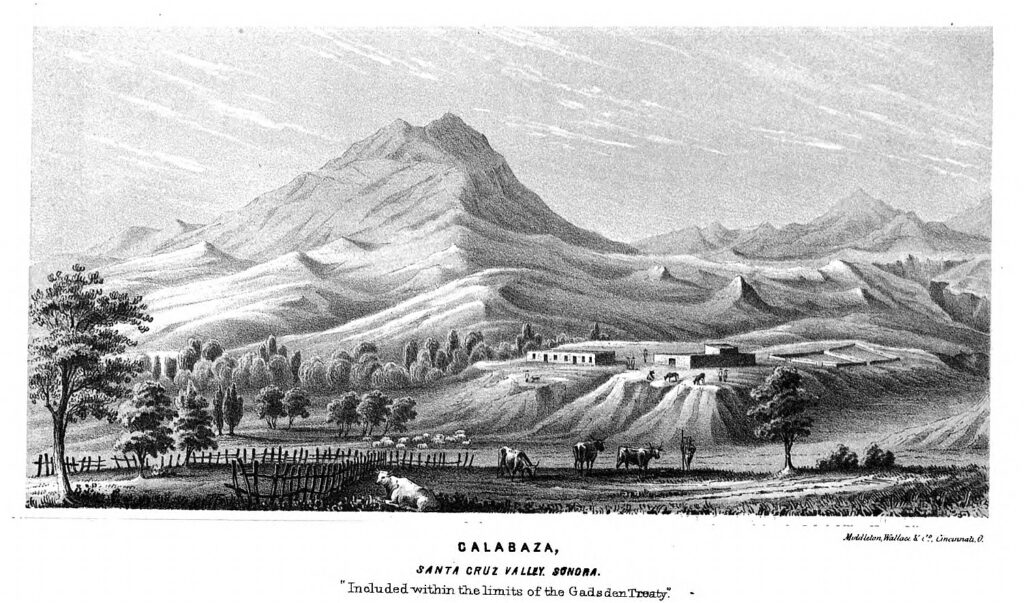

Despite its seemingly rewarding outcome, the Mexican-American War had cost American taxpayers a hundred million dollars in military expenses alone, and had faced vigorous opposition. Abraham Lincoln complained that Polk used the specious Thornton Affair as a casus belli, and argued the president had no constitutional authority to declare war — positions Lincoln’s rivals would turn against him every time he ran for office. Ohio Congressman Joshua Giddings declared the invasion aggressive, unholy, and unjust. Henry Thoreau refused to pay his poll tax in protest of both the war and slavery, and was briefly jailed for his demonstration. No less a soldier than Ulysses S. Grant, who’d fought in the war as a young officer, would later declare he was ashamed of it. But whether the war was a legitimate and appropriate act of self-defense, or La Intervención Norteamericano, a barely disguised land grab, the Mexican Cession dramatically expanded the American Far West, adding lands west of the Rio Grande and north of the Gila River to the frontier and extending the nation’s western boundary to the vast Pacific. New Mexico Territory was established in September of 1850. Then, in June 1854, Mexican President Antonio Lopez de Santa Anna signed the Gadsden Purchase, La Venta de la Mesilla, adding another thirty thousand square miles to New Mexico Territory for ten million dollars — making the area south of the Gila available for settlement.

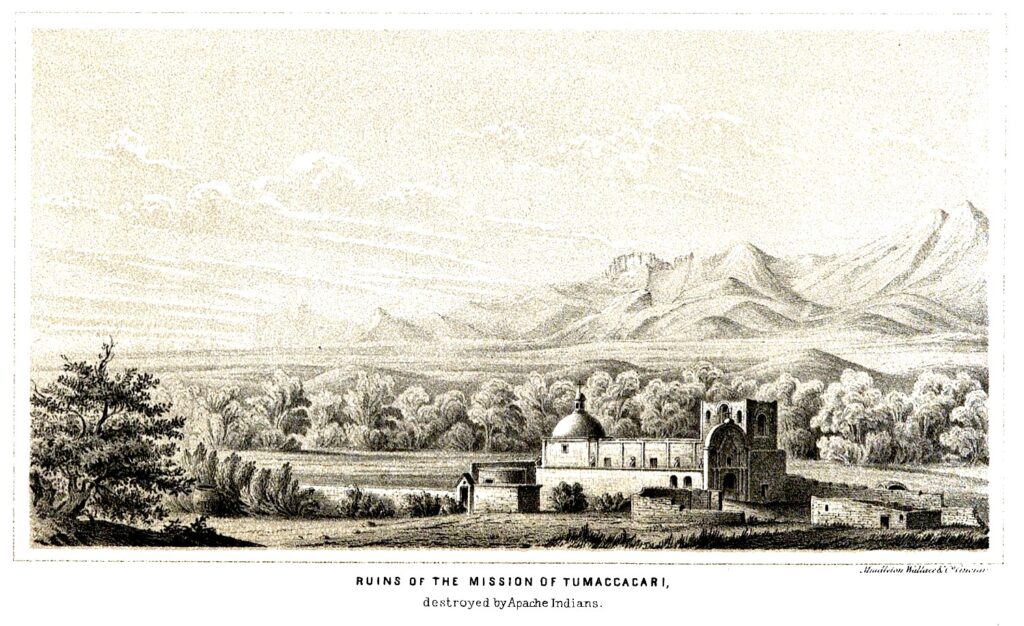

Politicians and military administrators wondered out loud whether the acquisition of Far Southwest was a bargain or a curse, some only half joking when they proposed America pay the republic to keep it. New Spain and Mexico had struggled to establish settlements along the rivers of the arid, seemingly barren frontier for more than two centuries, with mixed results. At times missionaries, soldiers, miners, and other colonists had succeeded in building thriving communities; at other times raiding Indians and marauding bandits had forced them to leave their homes and livestock and flee to a handful of widely-scattered presidios for protection, or temporarily abandon the frontier altogether. Fickle support from indifferent or unstable governments in New Spain and, after 1821, the Republic of Mexico compounded the settlers’ difficulties. When the Gadsden Purchase was signed and Mexico’s Pimería Alta and Apachería Alta were grafted onto the Territory of New Mexico, the area was generally as inhospitable as it had ever been. But word of the new frontier still spread, and many in search of adventure, refuge, fortune, or simply a home and an honest livelihood began to arrive.

In September 1855, a fifth of Tucson’s population signed a petition to the U.S. Army Commander of the Department of New Mexico requesting help in defending Tucson against Apache assaults. Most had Spanish surnames. The Tucsonenses knew the presidio’s Mexican dragoons would soon be leaving the Gadsden Purchase, and they were concerned their ad hoc militias alone would not be sufficient to repel large Apache raids or assaults. They needed armed soldiers to replace the dragoons and supplement the militias. Most of the signatures on the Spanish-language petition appear to have been made by its author, suggesting he or she may have acted in a notarial role, signing for citizens who couldn’t sign for themselves. Thankfully, the proxy scripted their names proudly and clearly.

American troops arrived a year later, but Enoch Steen had them camp at San Xavier, Tubac, and Calabasas before finally settling above the headwaters of Sonoita Creek the following July. Captain Richard Ewell had scouted the area between the Santa Cruz and the San Pedro Rivers and selected Ojo Caliente for its ready water and pasture. But the site became a mosquito-breeding marsh during rainy seasons, and both he and the major already had malaria. Colonel Bonneville, mine administrators, settlers, and the original Tucson petitioners asked why Fort Buchanan had been established so far from Tucson, or even the Sonoita homesteads and Tubac mining offices. Some winked and proposed in Spanish that it was a hidden fort, begging the question whether the soldiers were on a secret mission or simply avoiding the raiders. Boots were one of their first concerns, as the initial troops were all infantry. But their few serviceable horses and mules — needed for any effective pursuit of Pinal raiders — were subject to the same livestock sweeps affecting the settlers, so had to continuously be replaced.

Thirty months after the Tucsonenses petitioned General Garland for military protection, and sixteen after the army set up above the Sonoita, most of the homesteaders wrote Congress to request authorization to replace the soldiers with “volunteer Companies of rangers.” The soldiers were as affected by the Apache raids as they were, they complained, and many army contractors hadn’t been able to convert their government vouchers to gold specie, the most widely-used currency on the frontier. The already motherless Pennington family became so distressed they moved their homestead up the Santa Cruz, east of a nogal grove on the border, and retreated to a stone fortress.

Captain I. V. D. Reeve’s letter reports an 1859 event in which a criminal gang assaulted and killed migrant laborers on the Santa Cruz. The four murdered were Yaqui and mestizo workers in the Mescal Ranch distillery. When barreteros and tenateros heard the news, some left for Sonora, which affected mining operations. Farm workers left. Alarmed mine managers and contract farmers convinced the army to help lock up the offenders, but it would take some difficult cross-border diplomacy to get the miners back.

Although settlement in Santa Cruz Valley was encouraged, conditions in the late 1850s often threatened settlers’ safety, if not their subsistence. Records show they gained some control over circumstances by organizing ad hoc groups and pooling resources. Some called the exhausting, dangerous trials of migration ‘seeing the elephant’.

Readers are invited to examine these first-person accounts, evaluate them for veracity or bias, and discover what happened. References for all descriptions and graphic media can be found in the footnotes, captions, and selected bibliography.

This website comprises a reading list for American settlement on the Santa Cruz River, in an area called ‘Arizona’ in New Mexico Territory, between 1856 and 1861 [DDC 979.1042 — dc21; Santa Cruz Valley (Ariz.), frontier and pioneer life, 1856-1861; New Mexico Territory, frontier and pioneer life, 1850-1863; bibliographies, electronic; folk arts, electronic]. Numbered pages follow a rough chronology:

1. When Solomon Warner delivered his first train of goods from Yuma to Tucson in March 1856, he found a land in transition — and opportunity. Select this beleaguered Tucson link to begin.

2. a teamster’s education. early homesteaders.

4. Barbary Coast deportees. vagrants and villains.

5. filibuster on the Sonoita. an ad hoc court. the rise of Cochise.

Other documents from the Gadsden Purchase frontier may be found as files on the ‘electronic text facsimiles’ page, and as links to files on the ‘electronic links to resources’ page — accessed through the Documents drop-down menu.

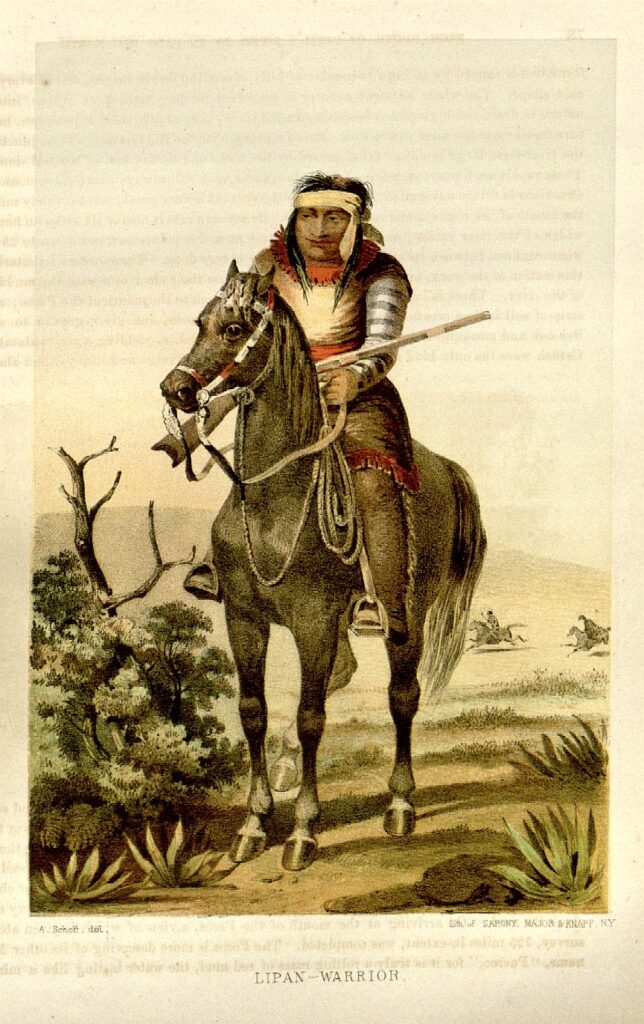

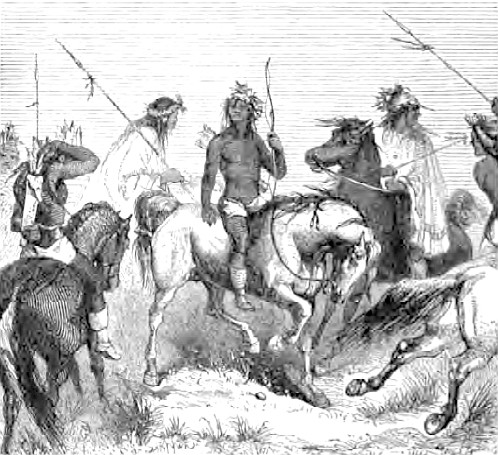

Both adversaries as raiders and allies as citizens, Apaches dramatically affected settlement on the Santa Cruz. New Spain had revived its attempt to move raiding Apache bands into mission settlements in the early 1790s. Two generations later, in 1851, fifty descendants of those resettled or manso Apaches from Tucson gave their lives defending Calabasas against raiding Apaches. But the mansos turned tables on the raiders three years later, securing the town and Governor Gándara’s four thousand sheep, and returning to Tucson with forty ears and the head of Romero, a captive who’d led the assault. The following year, Tucsonans petitioned General Garland for an American garrison to supplement bold militias like the manso Apaches’.

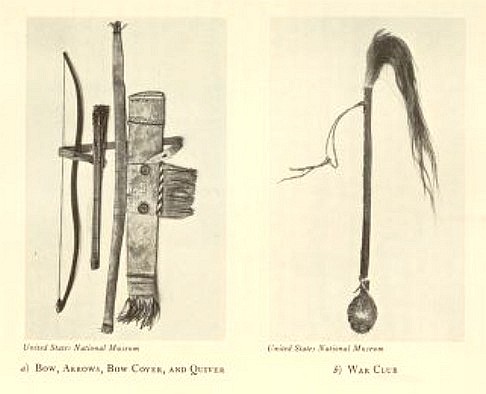

Documents describing a less martial Apache culture can be found on the ‘electronic links to resources’ page (Opler, Hoijer, Bourke), and the ‘electronic text facsimiles’ page (Basso and Castetter, if not Webster), and a collection of Apache artifacts can be viewed on the ‘ephemera’ page.

Librarian and researcher Charlotte Dean kindly contributed to this project at its inception. Bless her memory. Archivists Arthur B. House Jr. of the National Archives — Washington, DC; Kate Reeve at Arizona Historical Society — Tucson, Library and Archives; and Linda Whitaker and Susan Irwin for Sacks Collection of the American West, at Arizona Historical Foundation, helped locate key documents.

Sópori Books, PO Box 70183, Oro Valley, AZ 85737-0029; soporibooks@gmail.com. Also at soporibooks.substack.com.

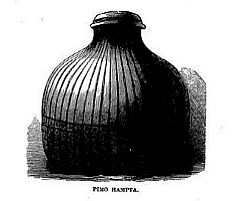

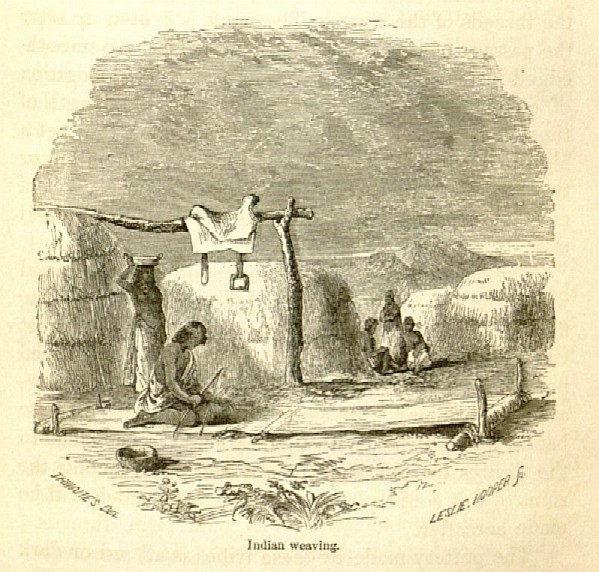

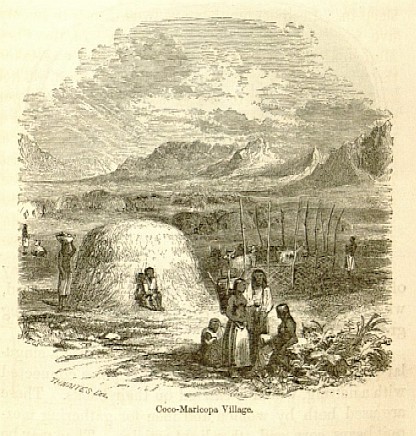

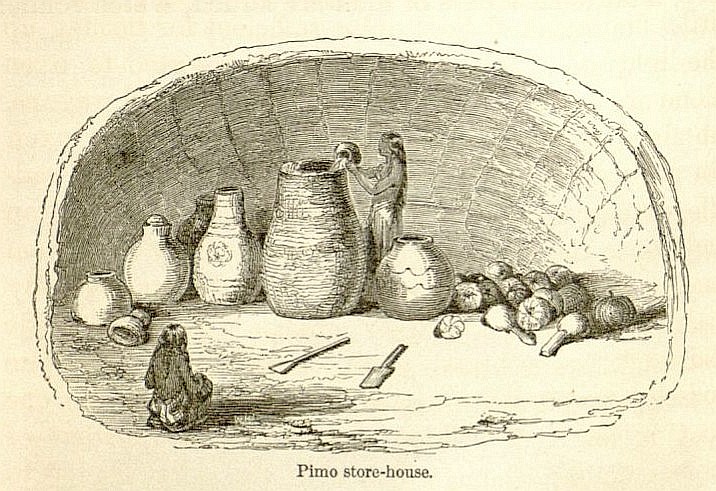

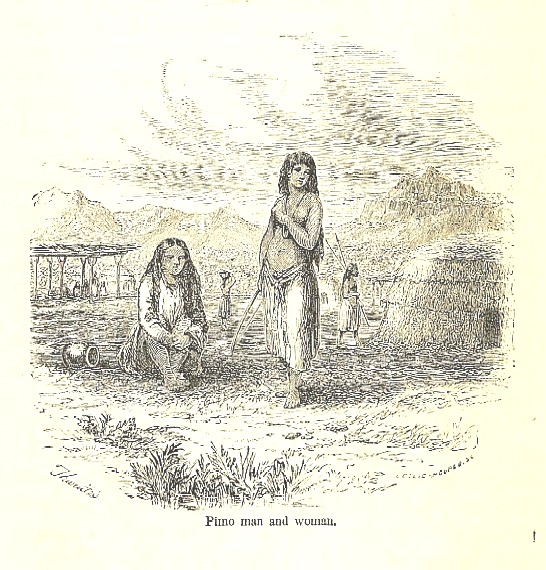

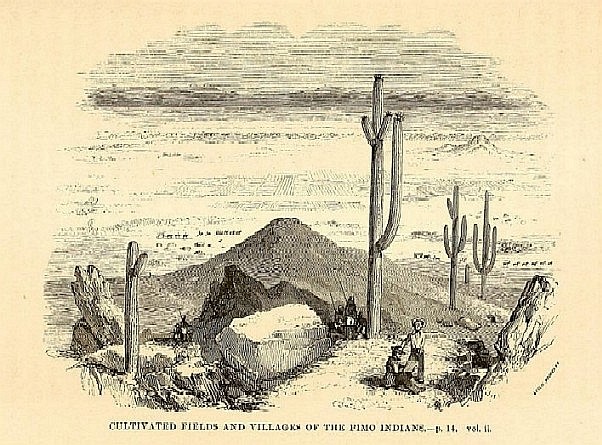

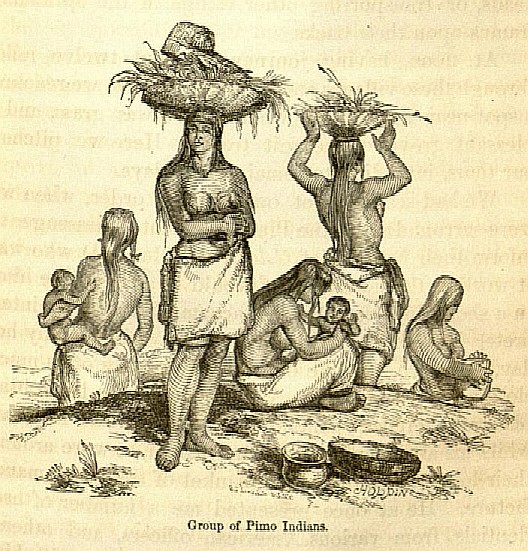

Image at top of page: Canon leading to Magdalena Sonora, John Russell Bartlett, pencil sketch (Canon between Bacuachi and Arispe, 1851); Seth Eastman, watercolor, ca. 1853, Rhode Island School of Design Museum, acc. 47.112.1. Below: Pimo hampta, John Ross Browne, 1864, in Adventures in the Apache Country: A Tour Through Arizona and Sonora, with Notes on the Silver Regions of Nevada (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1869), 109. Updated 2024-12-26.

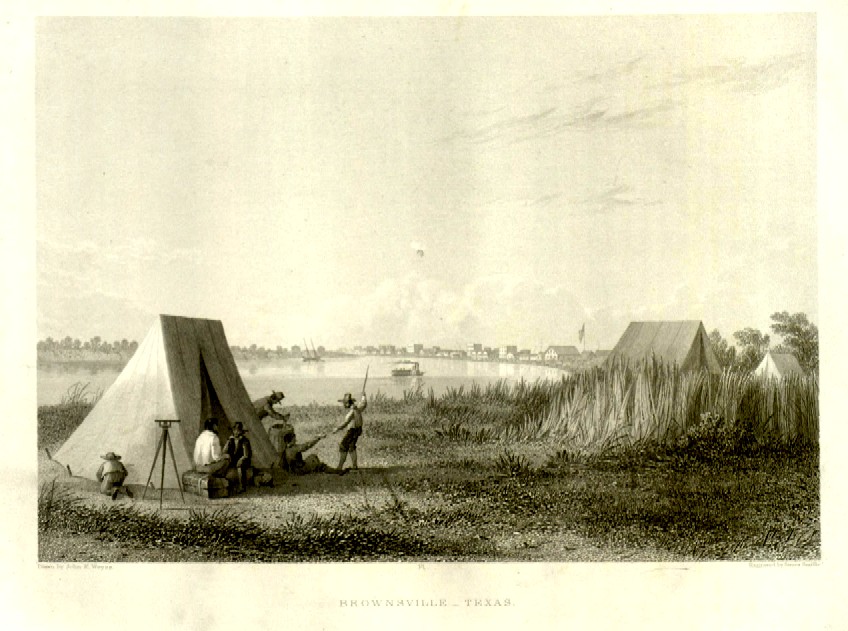

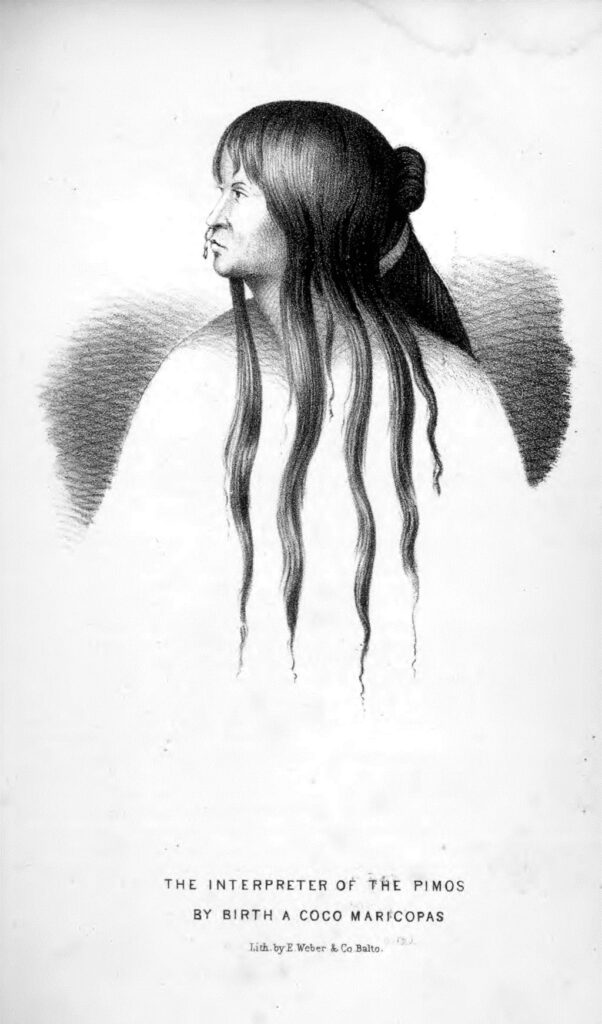

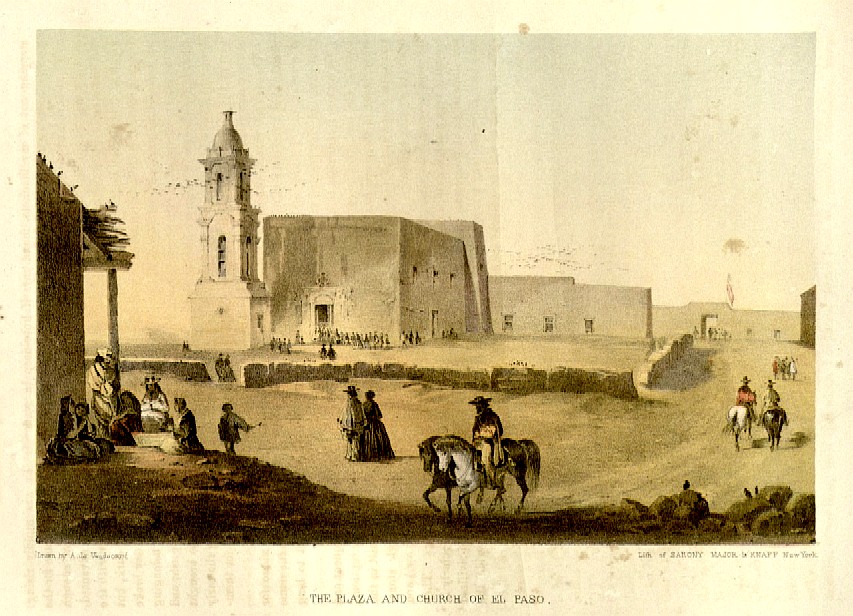

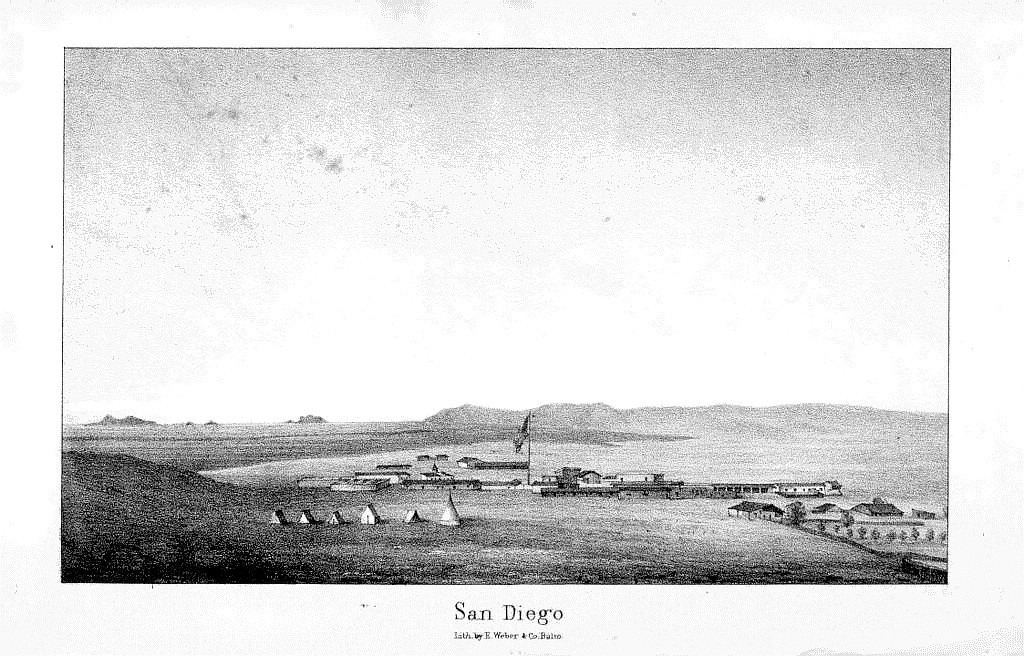

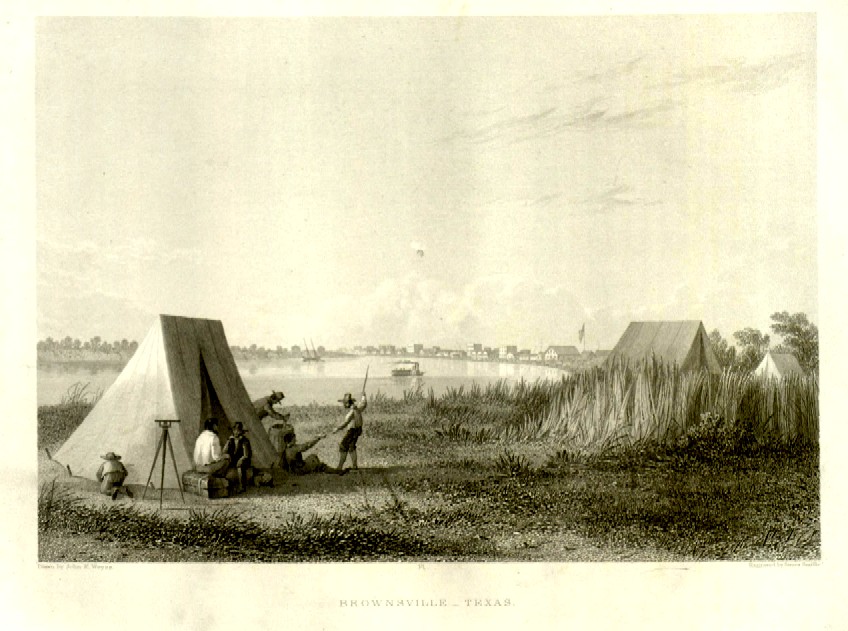

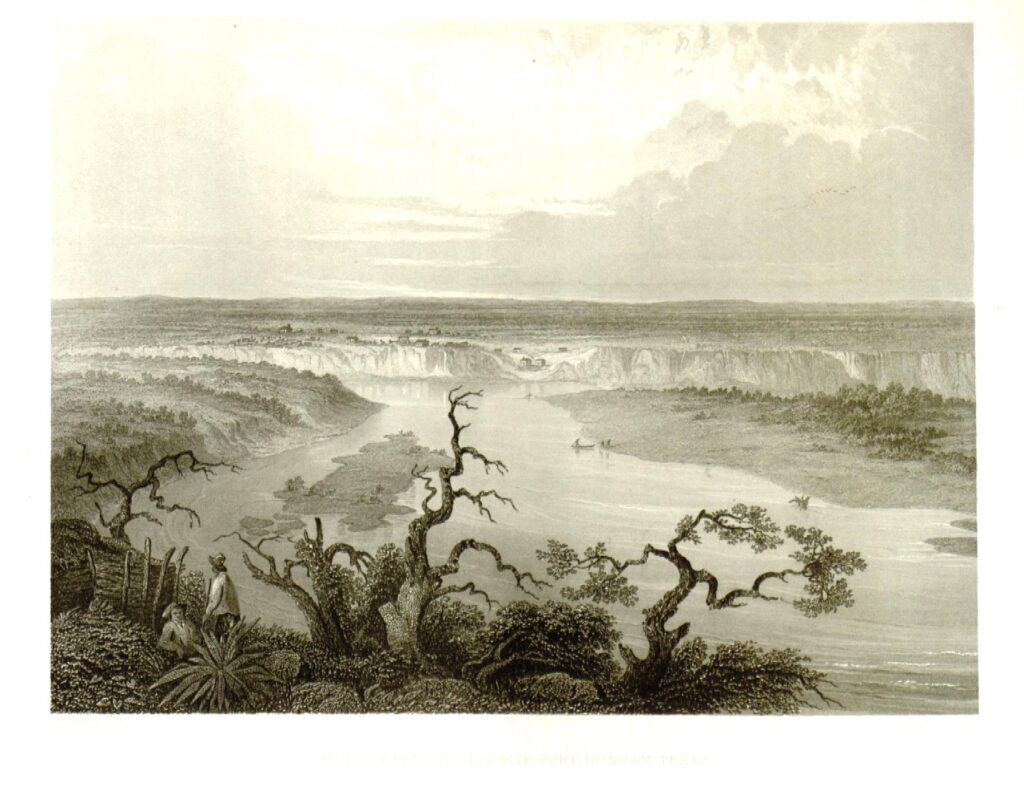

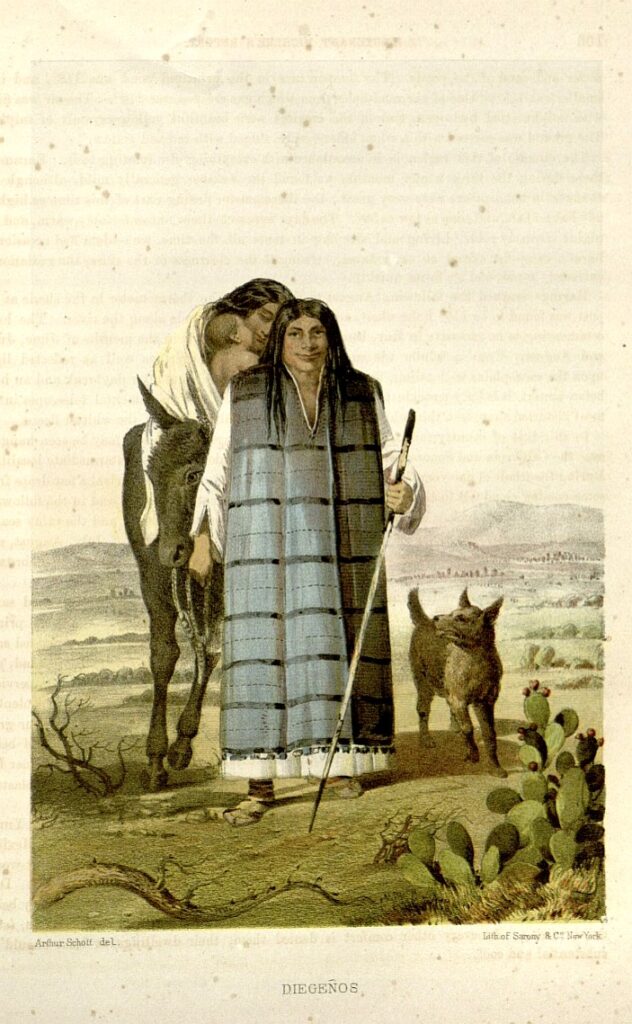

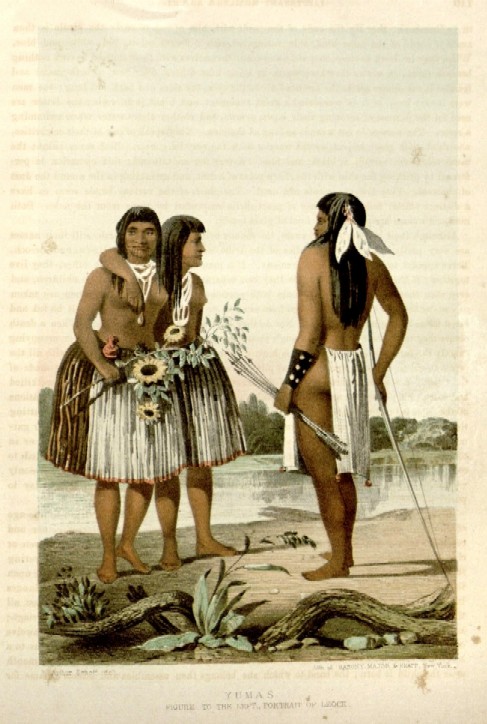

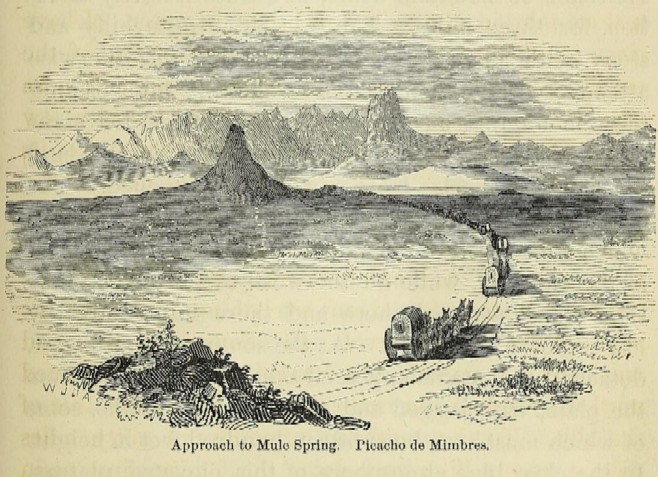

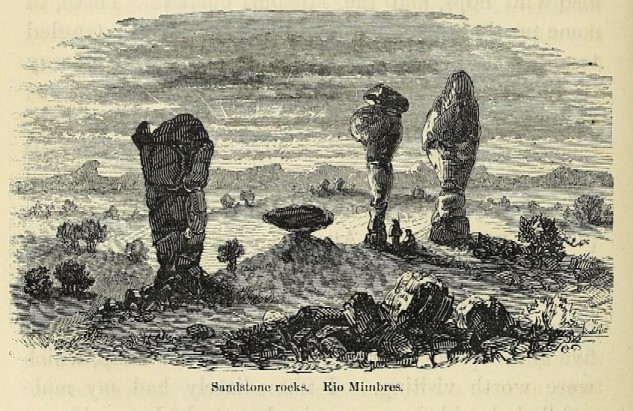

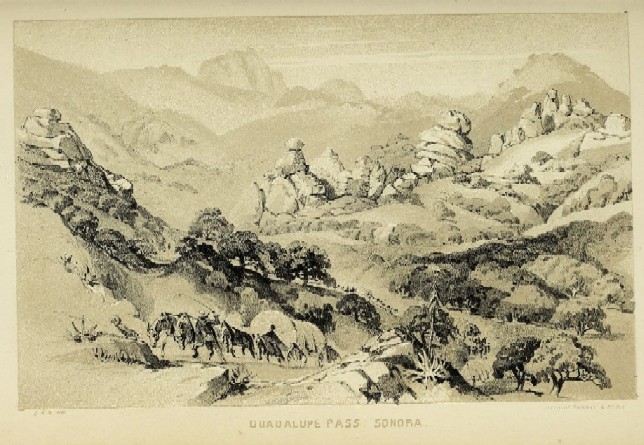

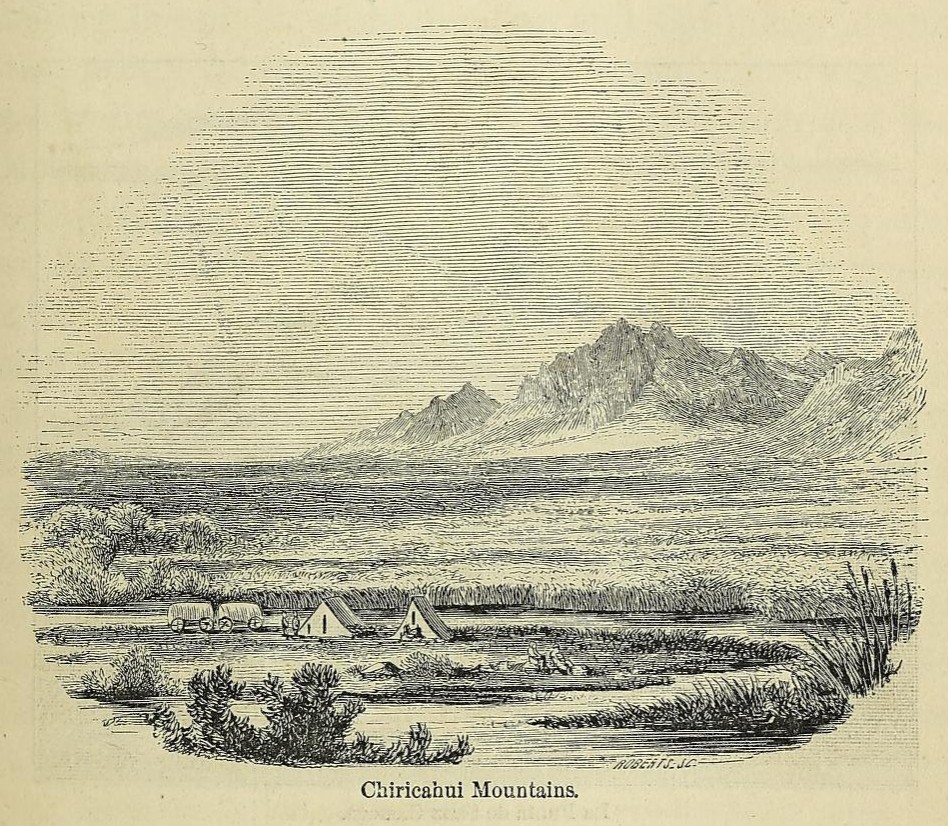

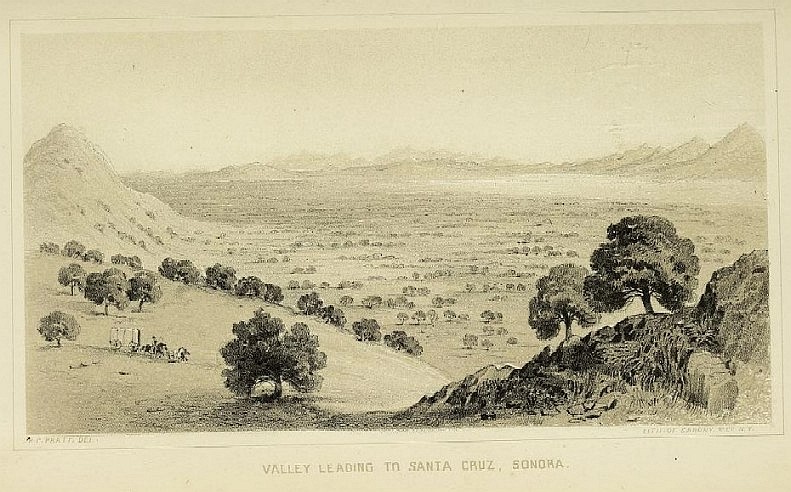

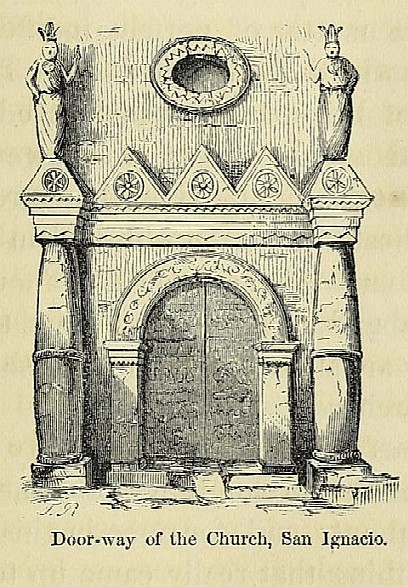

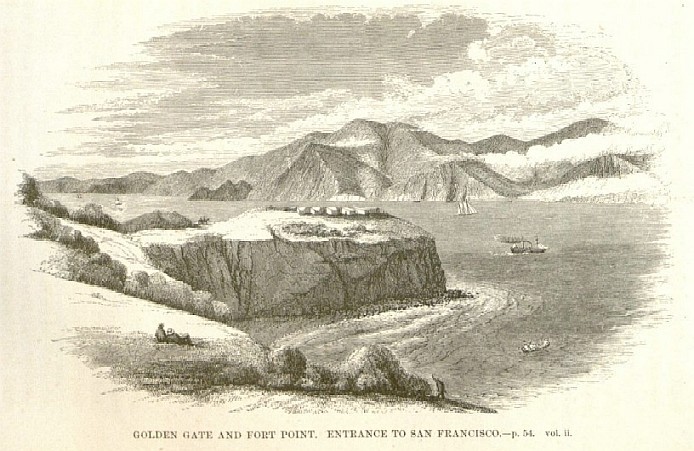

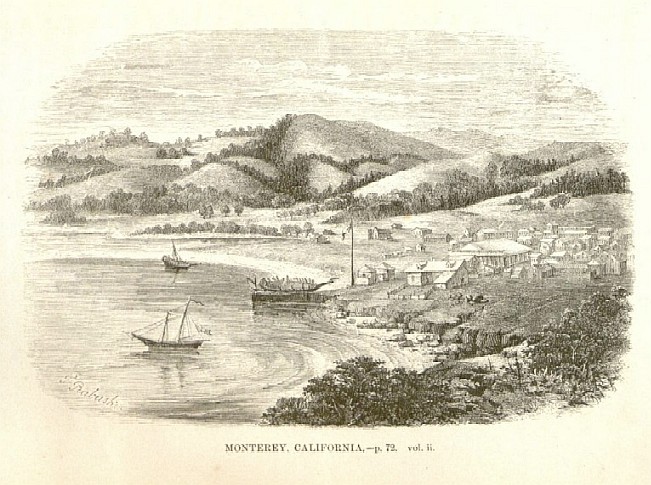

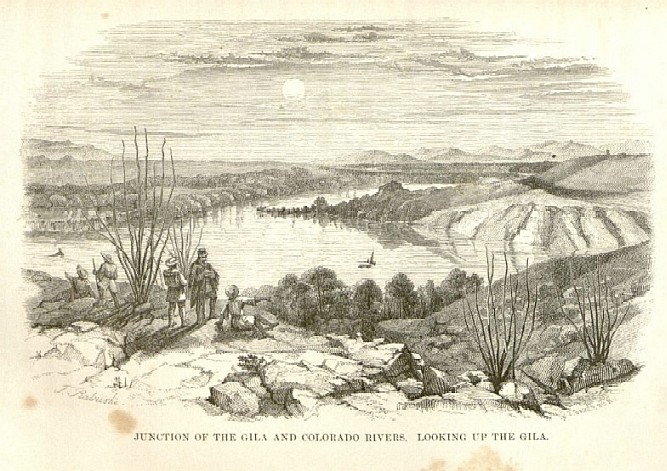

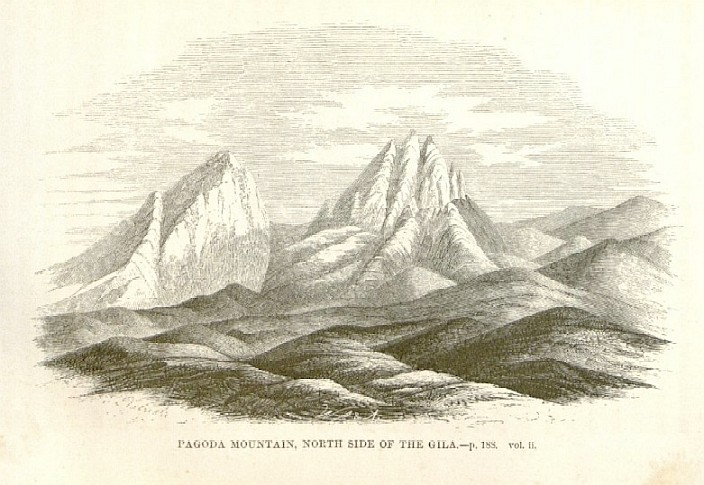

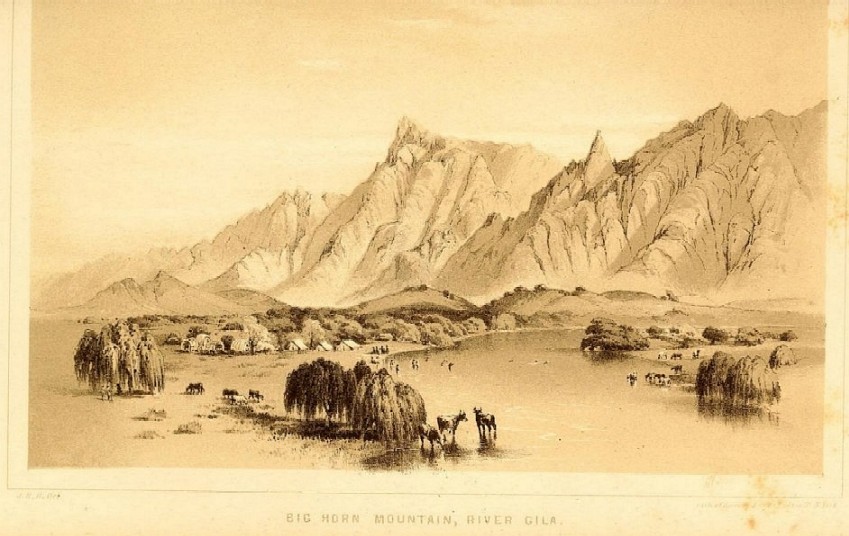

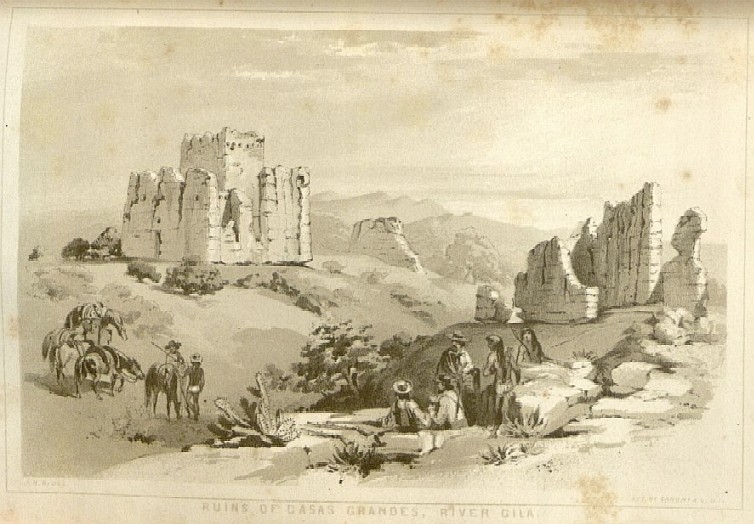

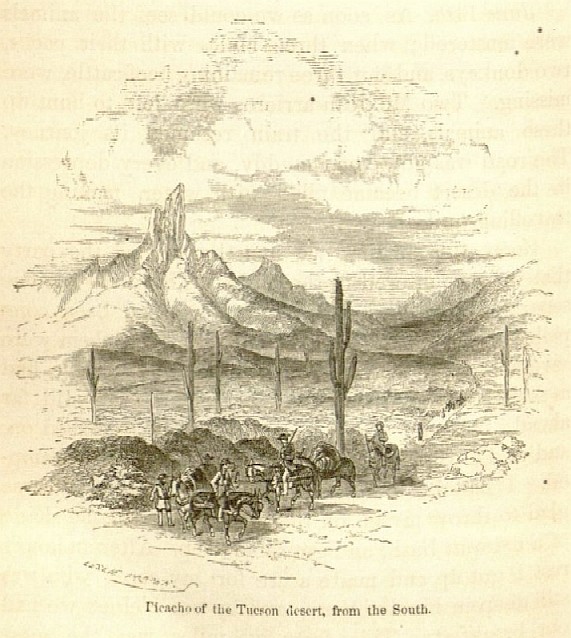

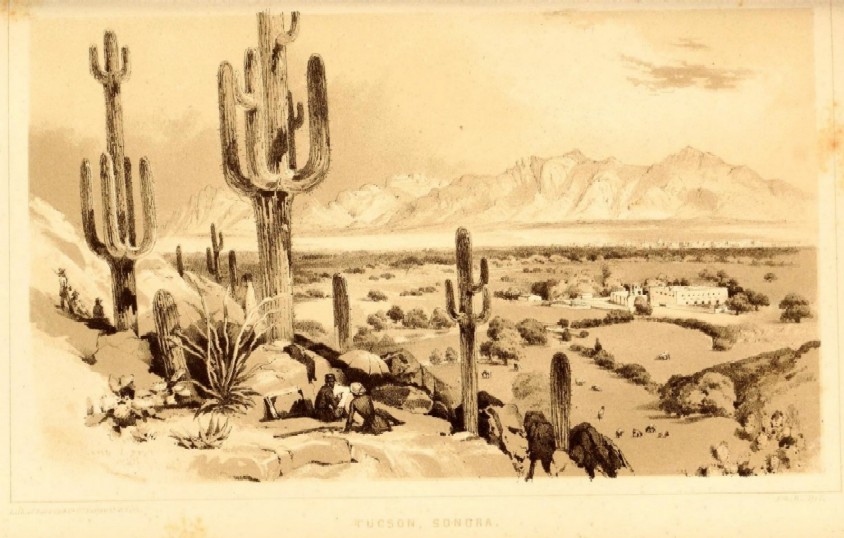

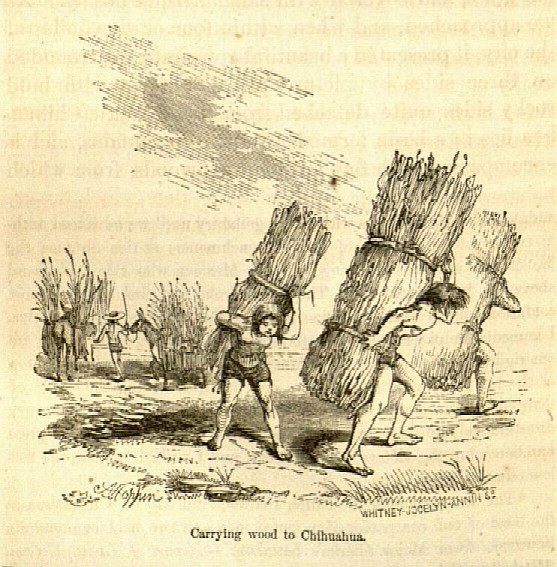

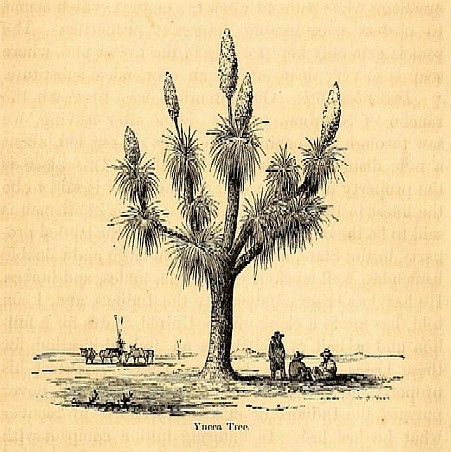

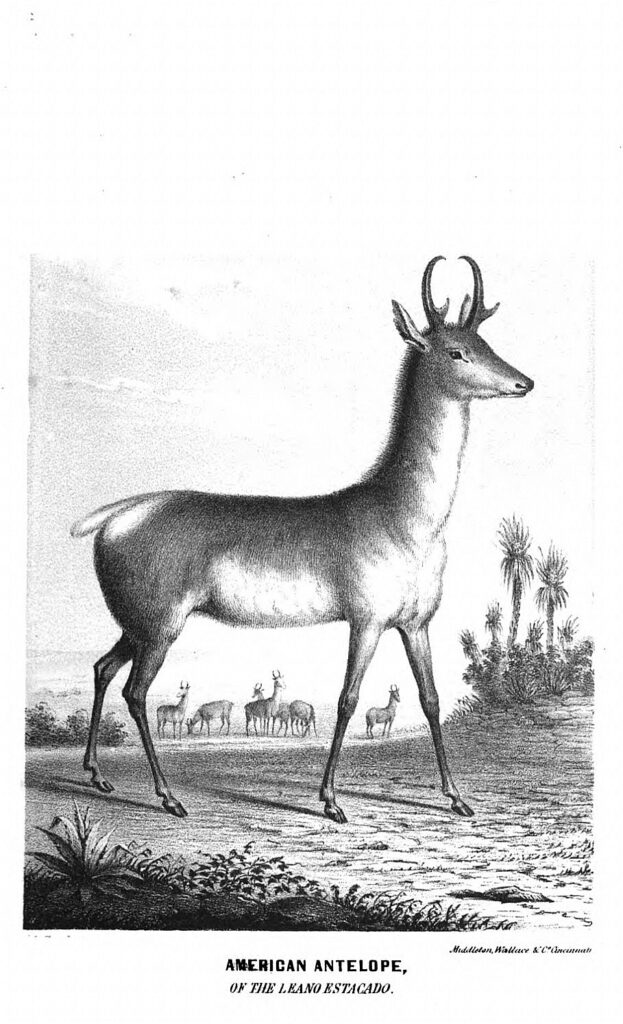

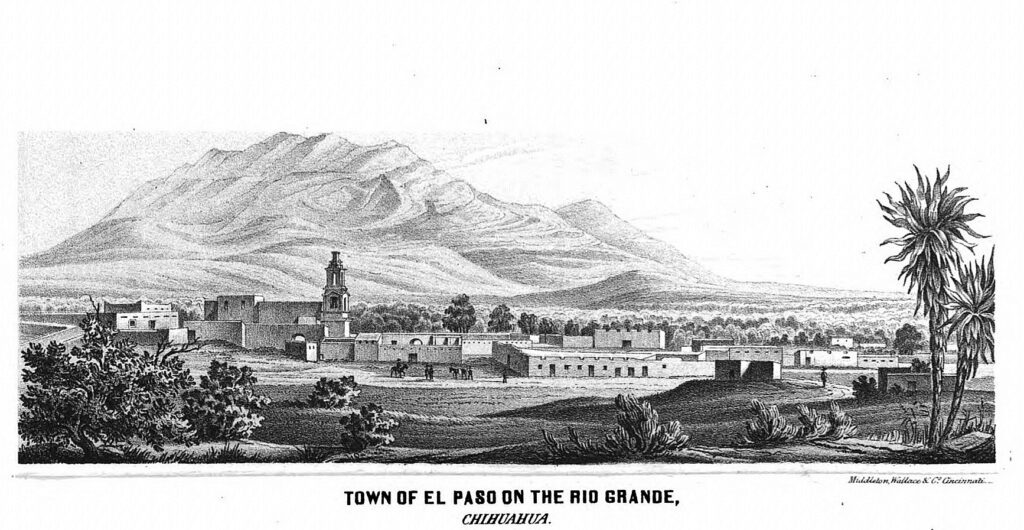

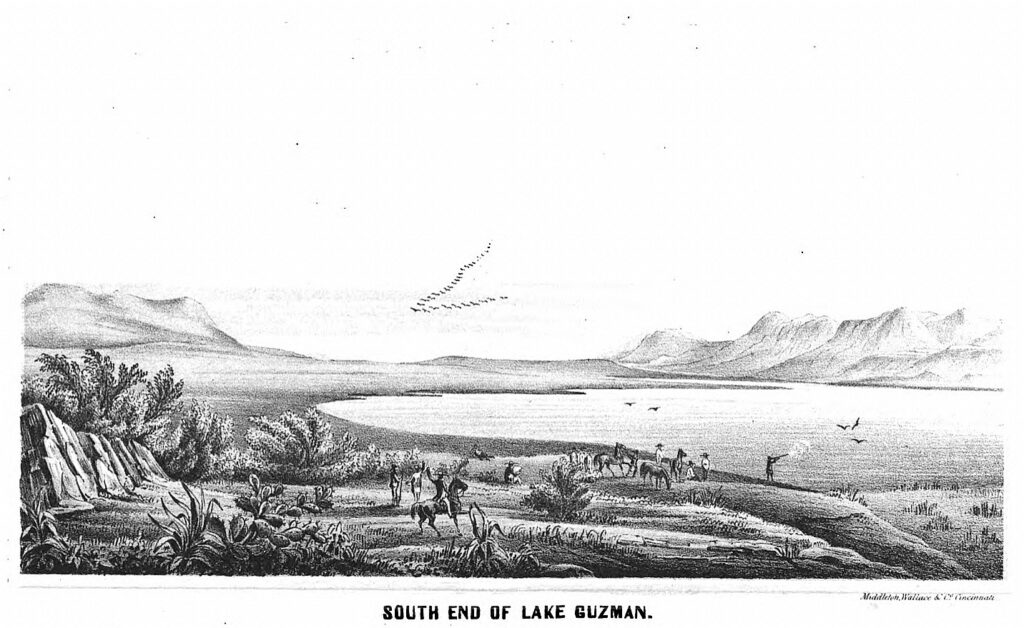

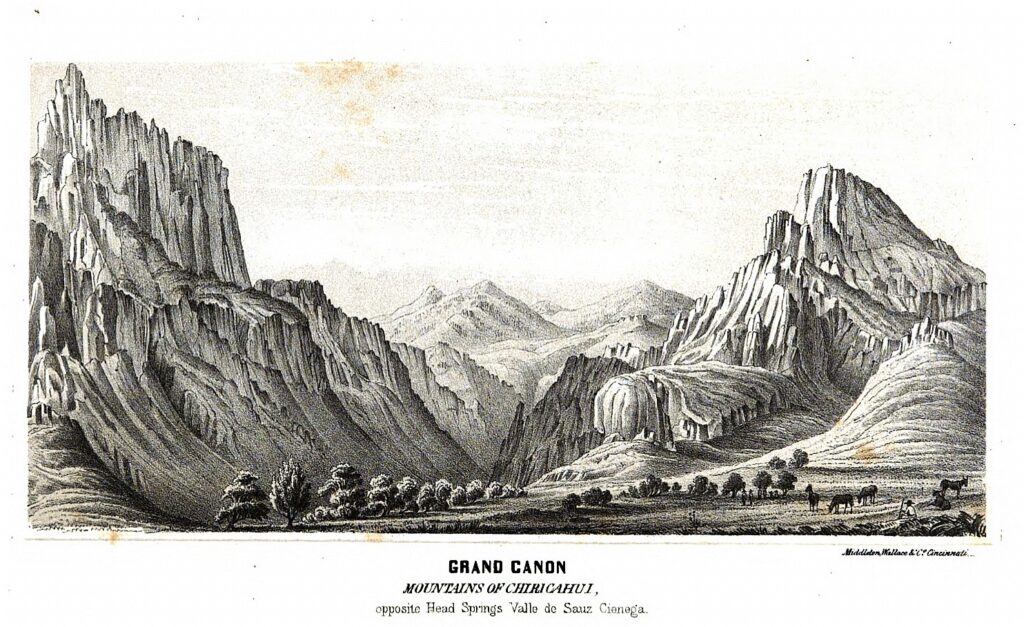

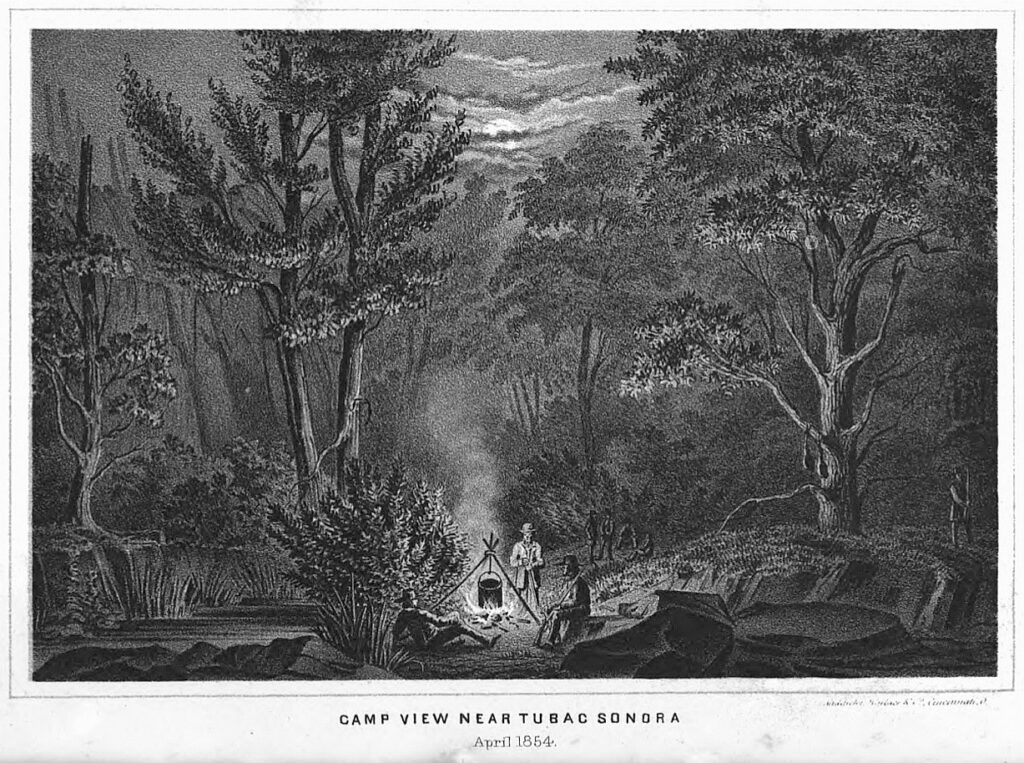

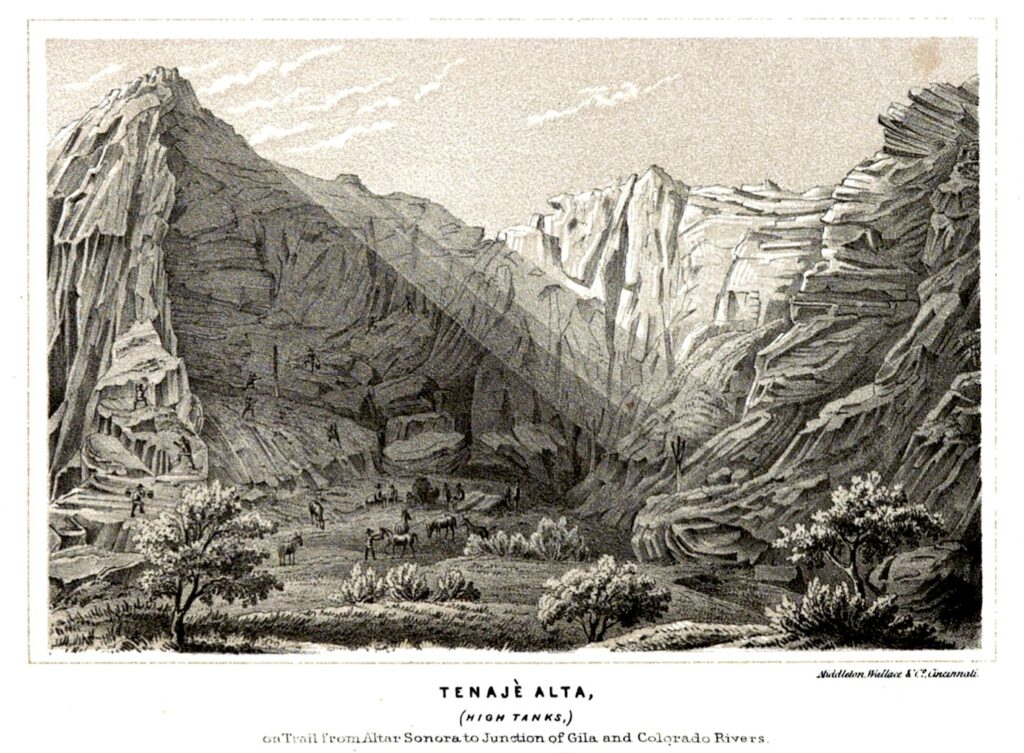

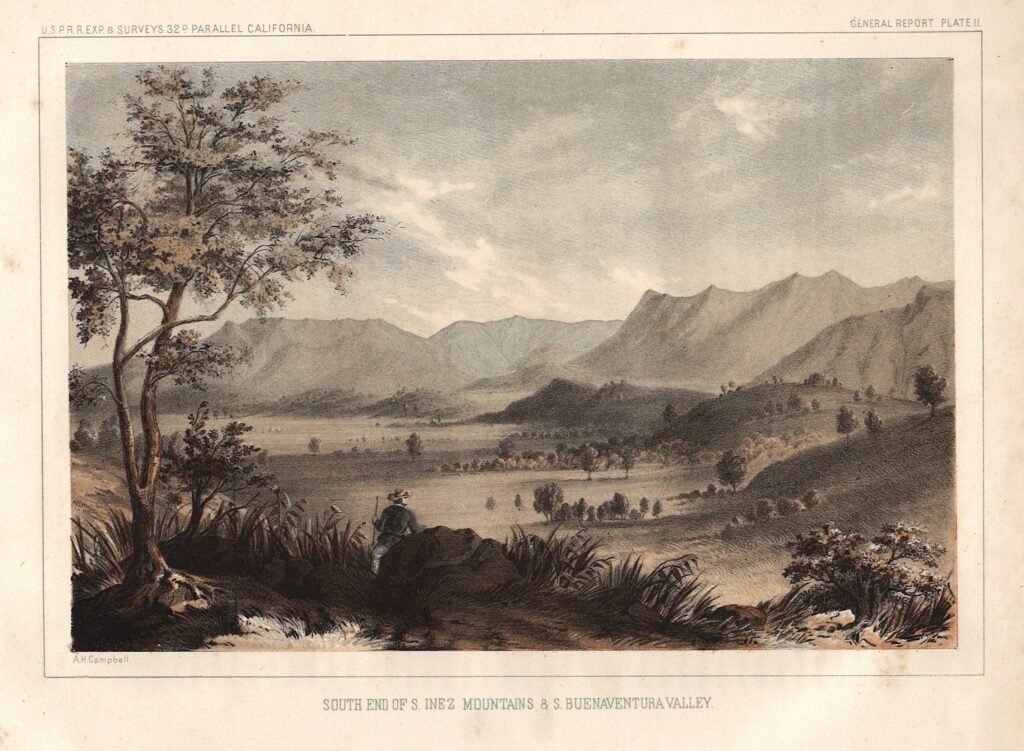

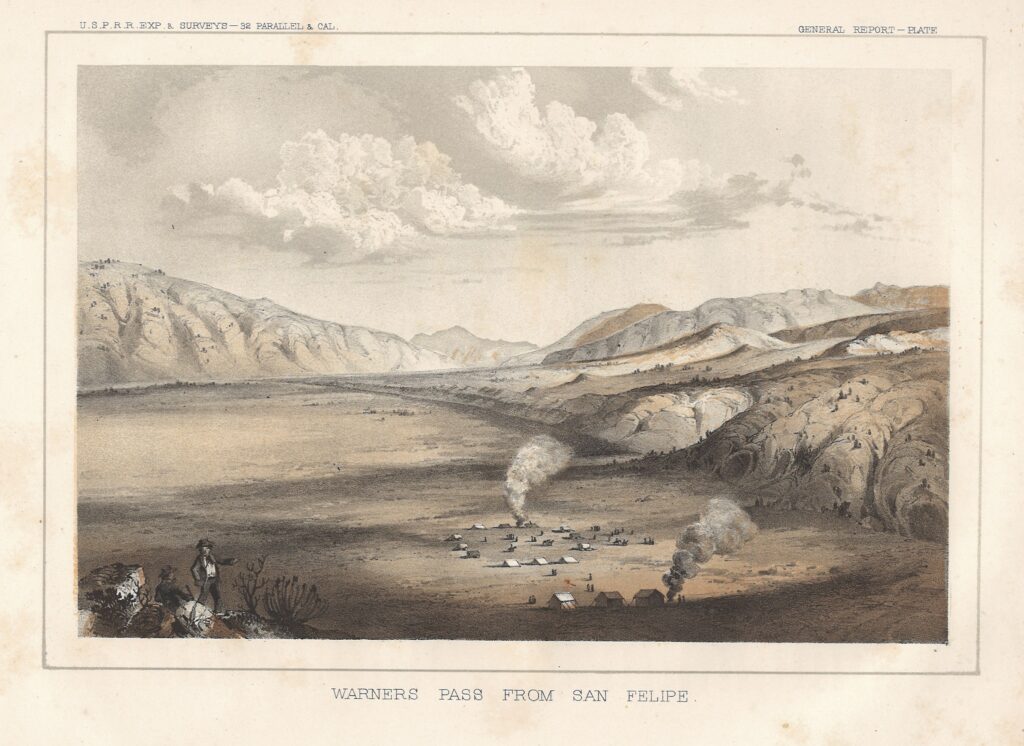

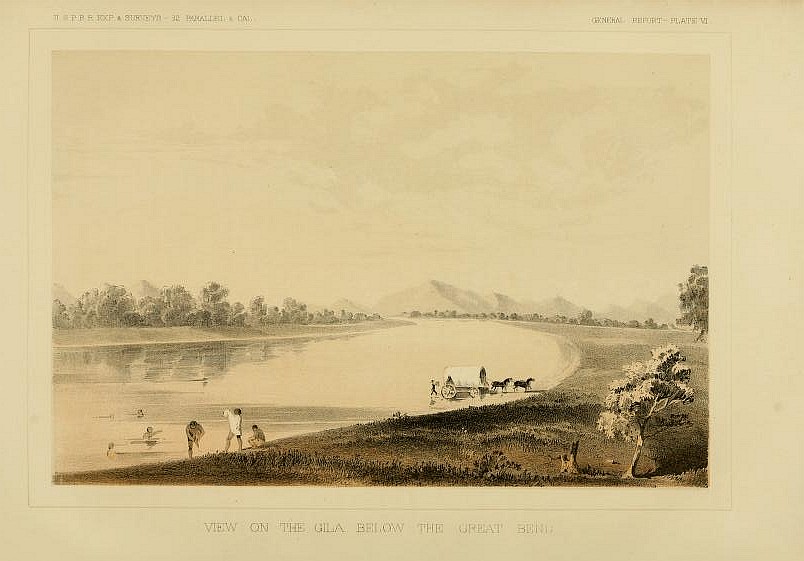

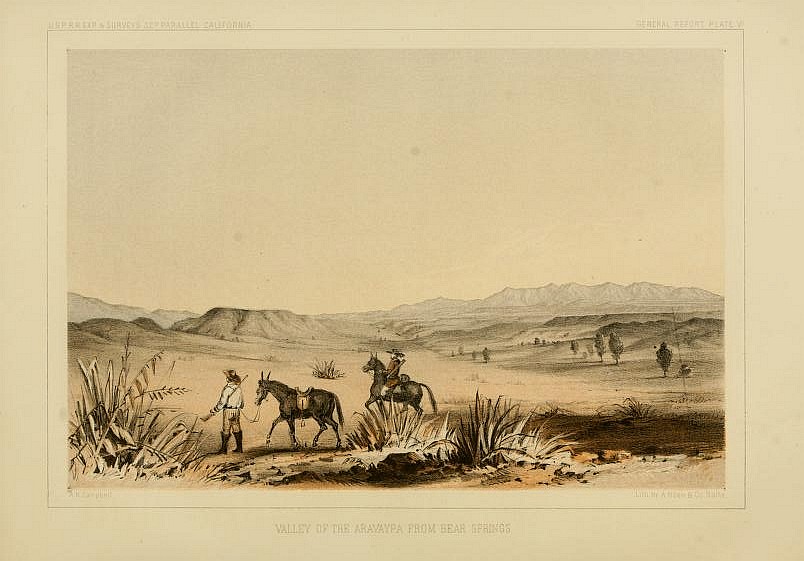

The middle of the nineteenth century brought government spies and railroad surveyors to the Gila Trail, Santa Cruz Valley and the Far Southwest. It was largely engineers and adventurers who recorded the technical profile of the landscape, and talented artists who later carved woodcuts and chemically etched metal plates to create lithographs. Artists, some of whom had received their training as officers at West Point, either accompanied the scientists or later added color and texture to their field sketches with paint. Dimensions of landscapes are usually accurate, thanks to the technology of camera lucida, but lithographs sometimes display alien or exotic colors due to the chemical processes required to make them, and the fact that some colorists may have never seen the landscape.

If they got the exact hues wrong or idealized their subject, we forgive them, but it seems equally likely the frontier between Brownsville and San Francisco impressed them so much that they enjoyed recording it for the less adventurous — in the drawing rooms of Cincinnati and Boston. Collectively, the images form a handsome legacy.

before photography: imagery of the Gila Trail and Santa Cruz Valley, 1845-1865

The artwork of John Mix Stanley, dated about 1845, can be found in W. H. Emory’s Notes of a Military Reconnoissance, from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego, in California, including parts of the Arkansas, Del Norte, and Gila Rivers (Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848).

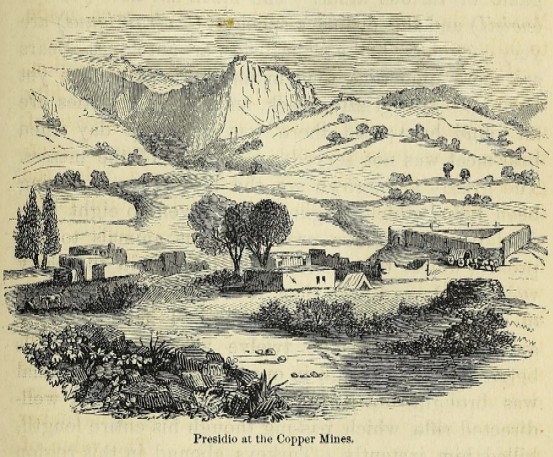

John Russell Bartlett and Henry Cheever Pratt, working about 1851, are in Bartlett’s Personal Narrative of Explorations and Incidents in Texas, New Mexico, California, Sonora, and Chihuahua . . . (New York: D. Appleton & Co., 1854).

Field artist John E. Weyss and colorist Arthur Schott, 1854, are in William H. Emory, The United States and Mexican Boundary Survey, Made Under the Direction of the Secretary of the Interior, William H. Emory, Vol. I (Washington: A. O. P. Nicholson, Printer, 1857), Part I, “Sketch of Territory Acquired by Treaty of December, 1853.”

Carl Schuchard, 1854, in Andrew Belcher Gray, The A. B. Gray Report: Survey of a Route on the 32nd Parallel for the Texas Western Railroad, 1854 (Cincinnati: Wrightson & Co., 1856).

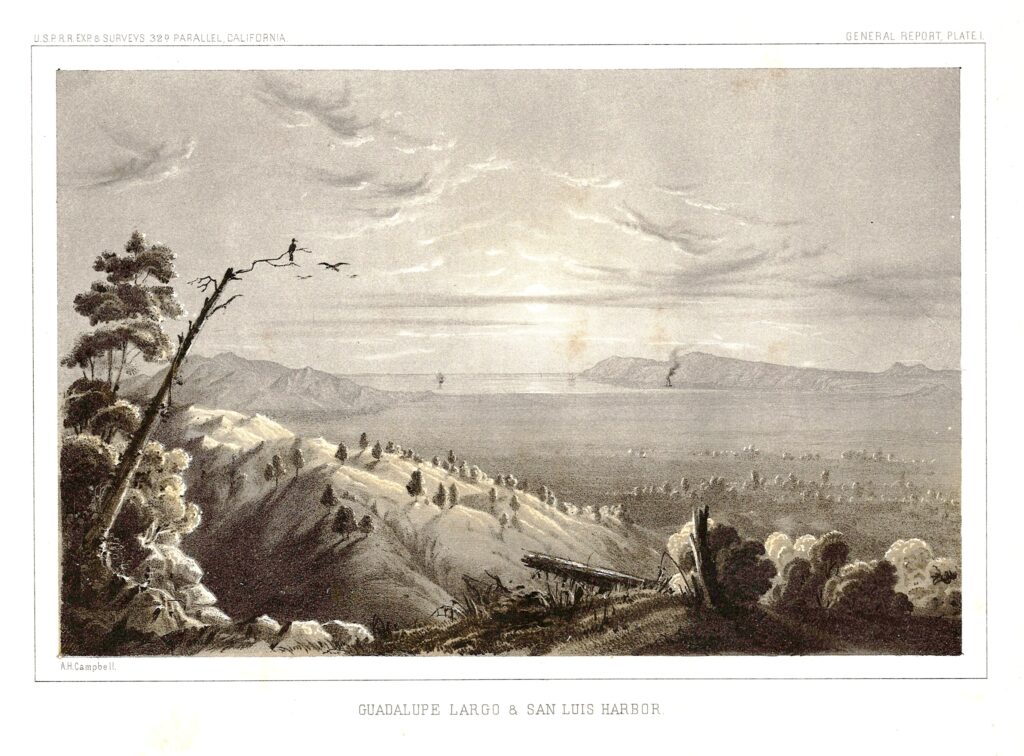

Alfred H. Campbell, 1855, in John G. Parke, Reports of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 1853-6, Vol. 7. (Washington: Beverley Tucker, Printer, 1857).

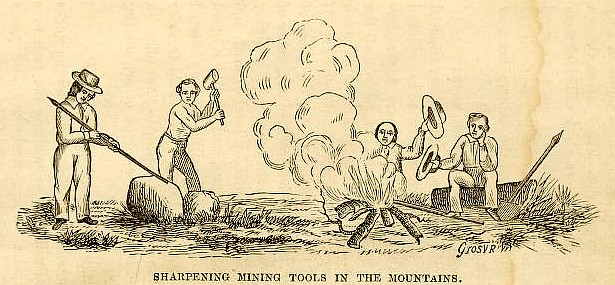

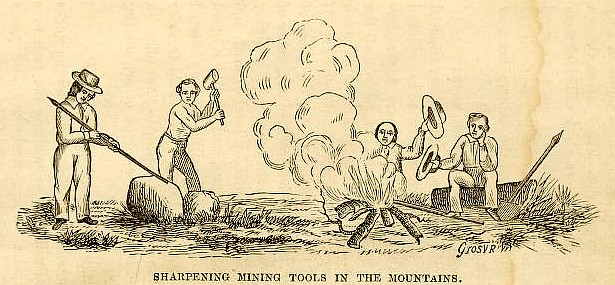

Horace Chapman Grosvenor, surveyor and mining administrator, in Report of the Sonora Exploring and Mining Co., Made to Stockholders, September, 1857 (Cincinnati: Railroad Record Print, 1857). A major figure in early mining, Grosvenor would be killed by raiding Apaches.

Celebrity adventurer and artist John Ross Browne sketched dozens of scenes on the Gila Trail in 1863, as civil war played out in the States, in Adventures in the Apache Country: A Tour Through Arizona and Sonora, with Notes on the Silver Regions of Nevada (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1869).

John G. Bourke would publish images of Apache cultural objects some twenty-five years later, in “The Medicine-Men of the Apache,” in the Ninth Annual Report of the Bureau of Ethnology of the Smithsonian Institution for the years 1887-1888 (Washington, D. C.: Government Printing Office, 1892).

Army officer Seth Eastman’s watercolors of Far Southwest field sketches brought warmth and texture to surveyors’ drawings, many of which were made using the new technology of a camera lucida. Thankfully, his work is also in the public domain, conserved and curated by Rhode Island School of Design Museum (risdmuseum.org), e.g.,

Great Canyon, River Gila; c. 1853, after a field drawing likely by Frank Wheaton. RISD accession number 47.112.9.

Canon Leading to Magdalena Sonora, c. 1853. RISD acc. 47.112.1.

Santa Cruz Valley, c. 1853. RISD acc. 47.112.13.

W. H. Emory recorded his expeditions’ findings in at least two volumes a decade apart, Notes of a Military Reconnoissance, from Fort Leavenworth, in Missouri, to San Diego, in California, including parts of the Arkansas, Del Norte, and Gila Rivers (Washington: Wendell and Van Benthuysen, Printers, 1848); and the United States and Mexican Boundary Survey, Made Under the Direction of the Secretary of the Interior, William H. Emory, Vol. I (Washington: A. O. P. Nicholson, Printer, 1857). Thankfully, artist John Mix Stanley was tasked with illustrating the former, and botanist Arthur Schott with the latter, in Emory’s “Sketch of Territory Acquired by Treaty of December, 1853,” In Part I.

We came across Biodiversity Heritage Library’s great portal to dozens of railroad survey links while looking for a particular essay: https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/bibliography/11139 (also listed on the ‘electronic links to resources’ page). The site helps readers locate information in the maze of reports and other data in the eclectic series on the American West, which was published between 1855 and 1860, and saves hours to months of tedious work. We found our report in Parke, for example, and as is often the case, the search delivered unexpected rewards.

Parke, John G. Reports of Explorations and Surveys to Ascertain the Most Practicable and Economical Route for a Railroad from the Mississippi River to the Pacific Ocean, 1853-6, Vol. 7. (Washington: Beverley Tucker, Printer, 1857). Parke posts a translation of a 1777 report and plea from Tubac’s Manuel Barragua to Captain Pedro Allande Savedra in Tucson, as Appendix C in Volume 7. Barragua writes that New Spain’s colonists farther up the Santa Cruz became so desperate after the reassignment of their garrison to Tucson, they burned Calabasas to thwart raiders. [Enlarge page facsimiles to read.]

We found the essay we were looking for, “From the Pima Villages on the Gila to the Rio Grande, Near the 32d Parallel of North Latitude,” as Part I, No. 2 of Volume 7. In addition to text, it holds lithographs adapted from field sketches made by illustrator Alfred H. Campbell in 1854 as he trekked up the Gila to the San Pedro River with a mule train, then down the San Pedro to rejoin Parke on the wagon road. The generous landscapes of Central California, the Gila River and San Xavier del Bac were serendipity.

Mining engineers and surveyors like Horace C. Grosvenor and Herman Ehrenberg joined illustrators Arthur Schott and Carl Schuchard to propagandize the nascent mining industry, leaving a remarkable collection of images and maps from the late 1850s.

To view a selection of these images, those of J. Ross Browne in 1864, and Seth Eastman’s watercolors of Gila Trail field sketches at Rhode Island School of Design — click on this link to ephemera.