If you’re missing a narrative, you’re not alone. Kevin Starr noticed our lack of explanation in 1975, in a monograph on early voyages he kindly reviewed. Many of its arcane sources — like Hakluyt’s Voyages, once closely circulated in special collections — now float freely in the electronic ether. We scroll the diaries of piratical explorers online in our kitchen. As much as we appreciate Kevin’s remarkable body of work and its informed tradition, we’re glad we kept collating first-person accounts of the Far West. Primary data are a window to events, and can be confirmed or tempered by other sound witnesses and records.

Nicholson Baker describes how historic data are photographed, access to the new microforms or facsimile files is maintained, and sources are conserved in Double Fold: Libraries and the Assault on Paper (New York: Random House, 2000). Some libraries ‘de-accession’ historic volumes after photographing them, or anytime they have unneeded copies. (‘De-accession’, like its equally inbred cousin ‘deselection’, is librarian Newspeak for ‘discard’. Used as a verb, we swear. Most literate humanoids would call it weeding, as one weeds a garden.) Many libraries offer their discards to other libraries, non-profit organizations, and private parties before sending them to pulp mills for recycling. But brokers rescue some volumes and list them in digital stores through portals like BookFinder.com. We recently found a handsomely rebound surplus set of Bartlett (1854) from the Boston Public Library, through such an independent bookseller. The more source materials in circulation — whether privately-held hard copies or public electronic facsimiles — the easier it is to reconstruct events and test explanations.

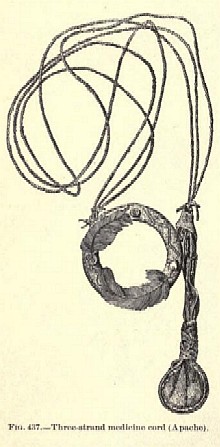

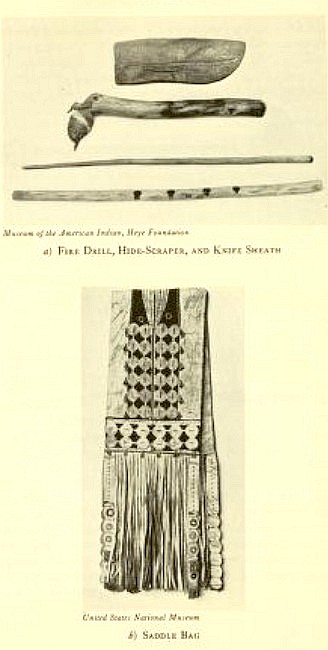

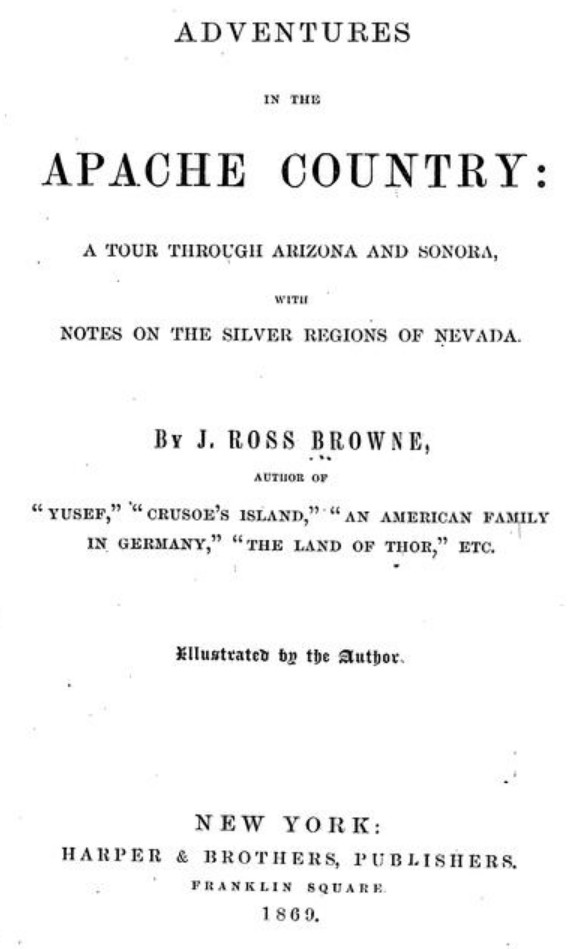

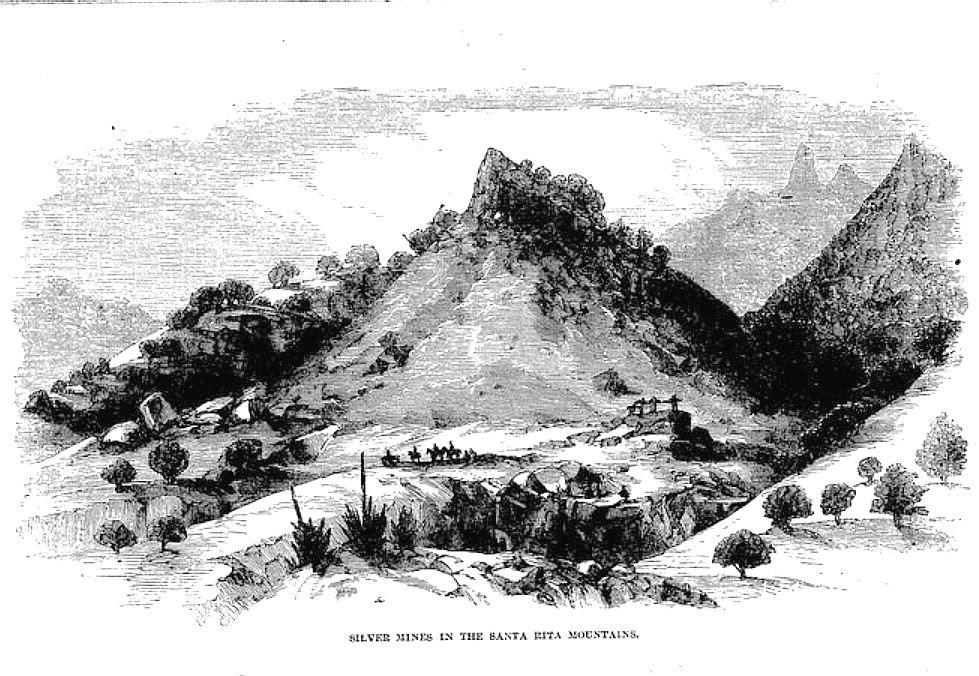

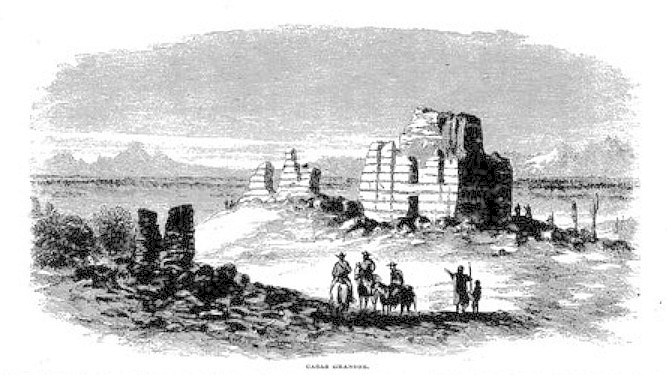

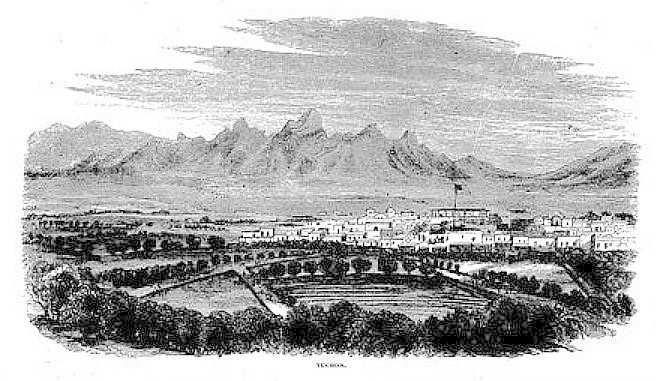

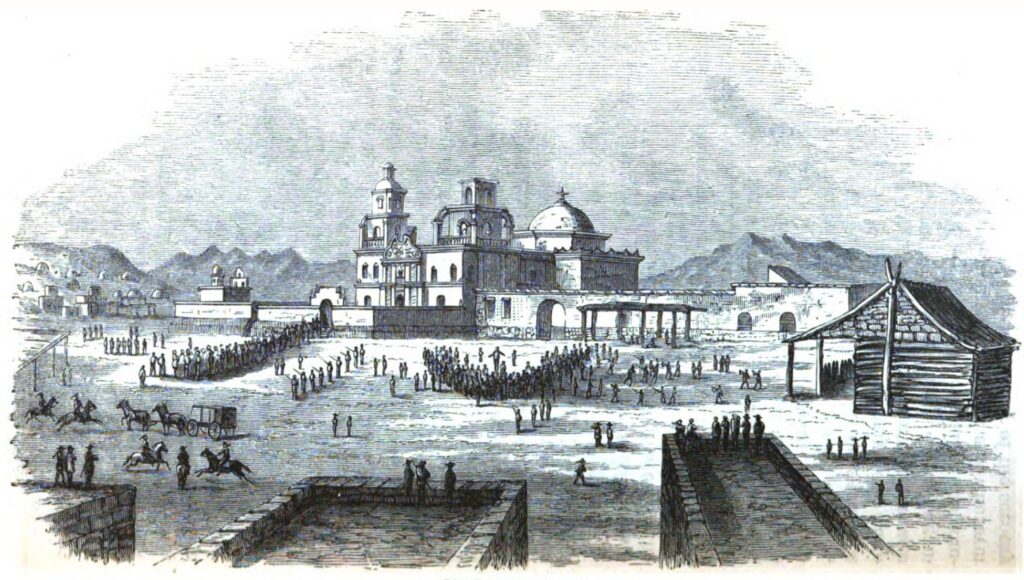

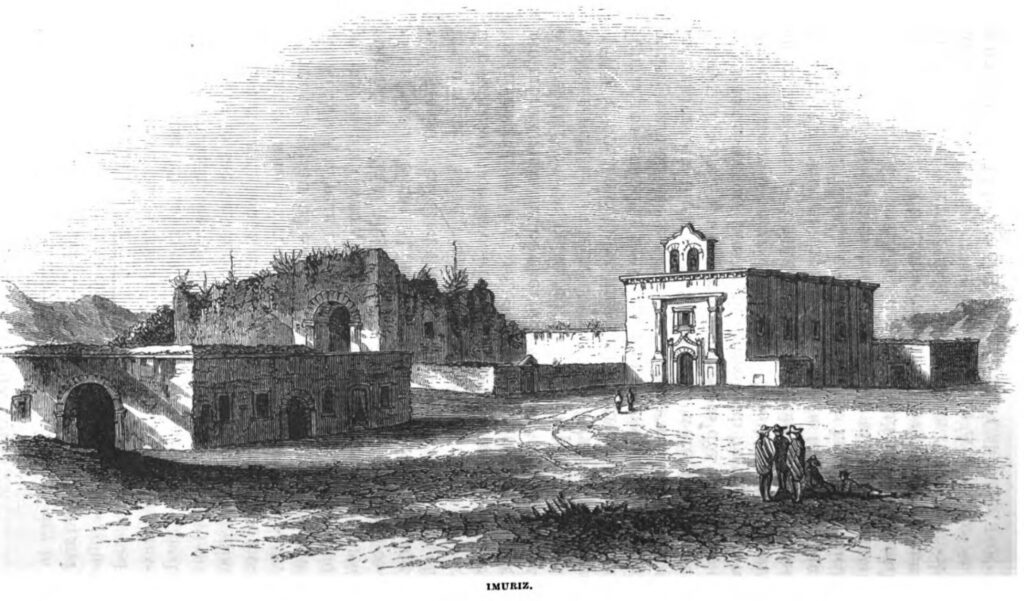

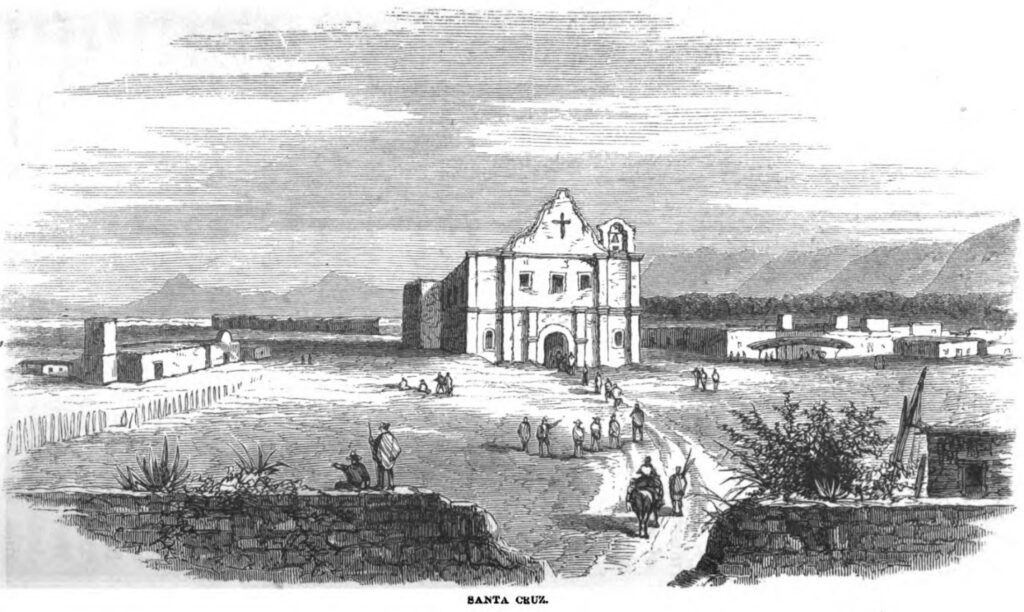

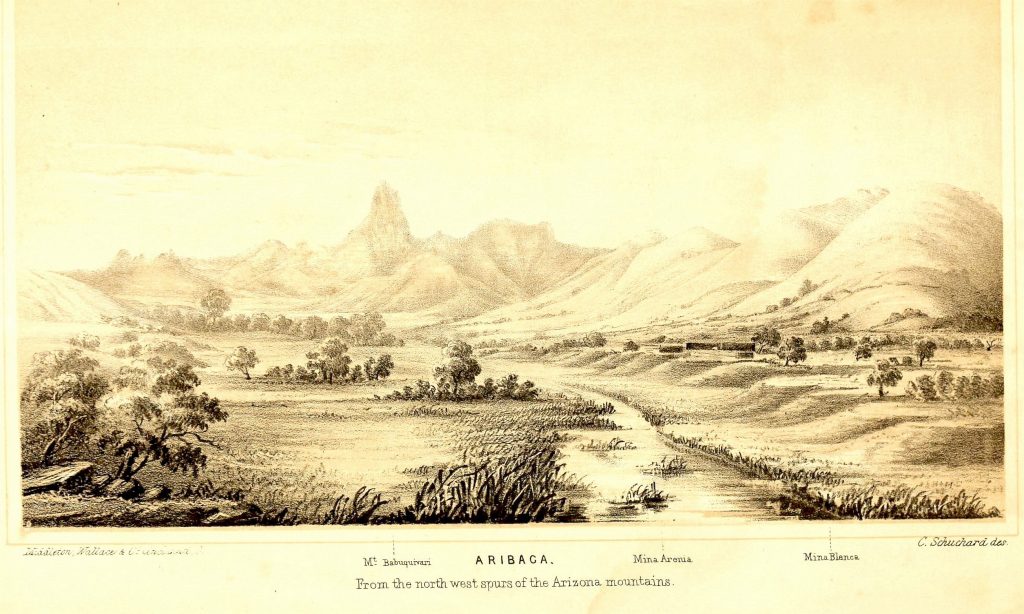

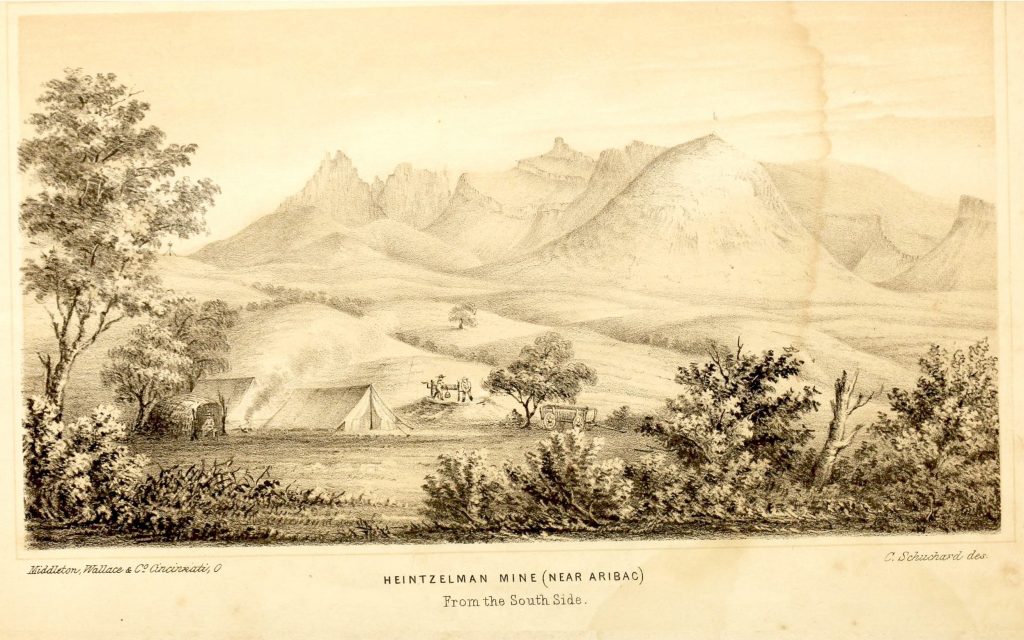

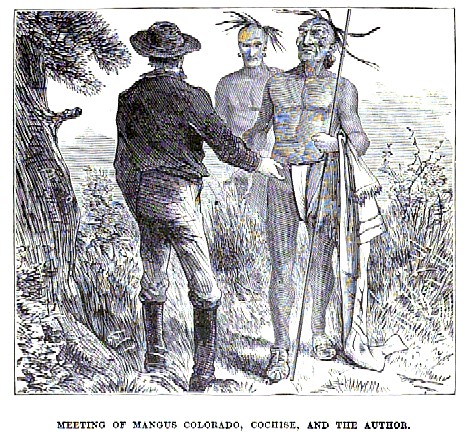

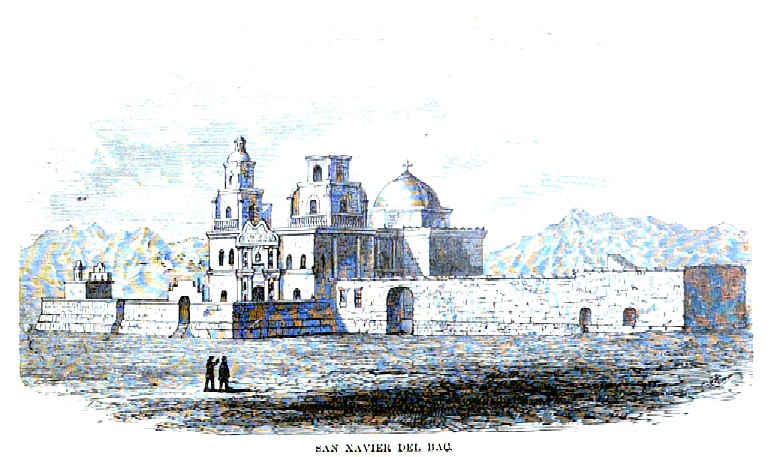

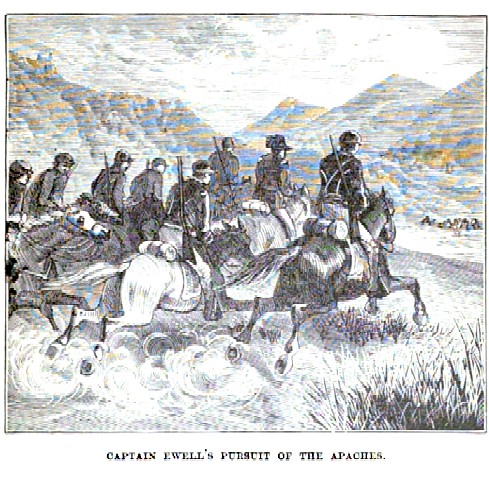

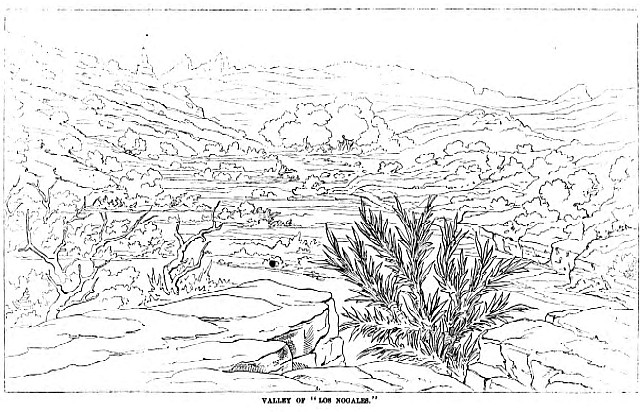

The energetic special agent to Oregon Country John Ross Browne left quite a graphic record of the 1864 Gadsden Purchase frontier in Adventures in the Apache Country: A Tour Through Arizona and Sonora, with Notes on the Silver Regions of Nevada (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1869):

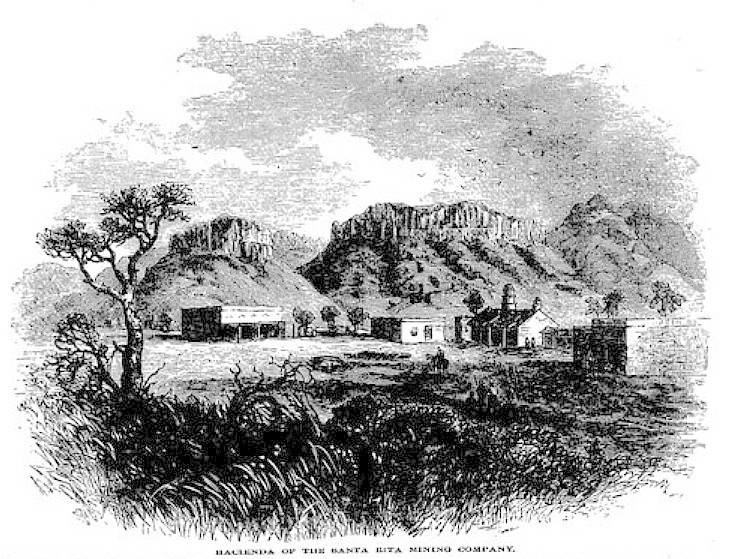

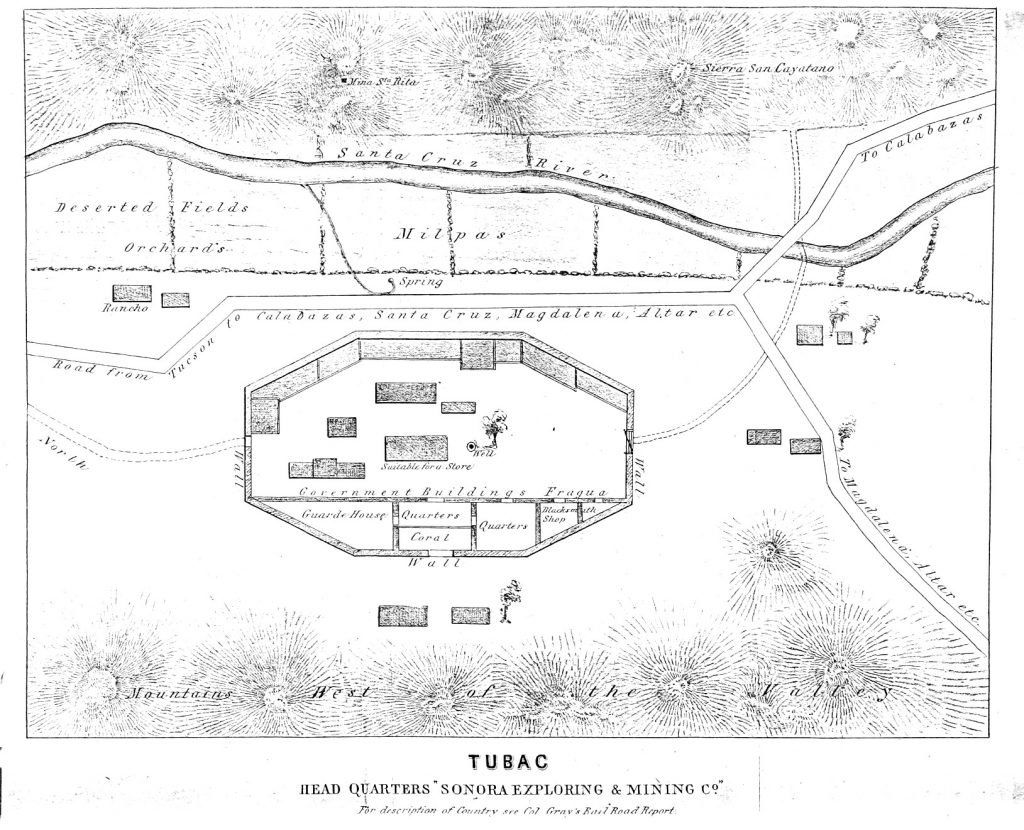

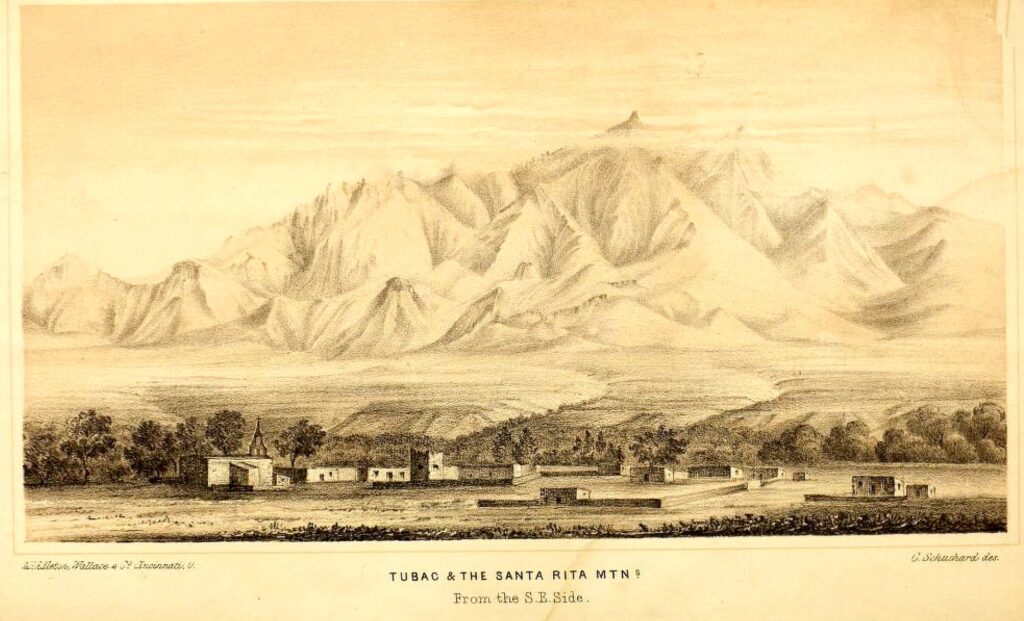

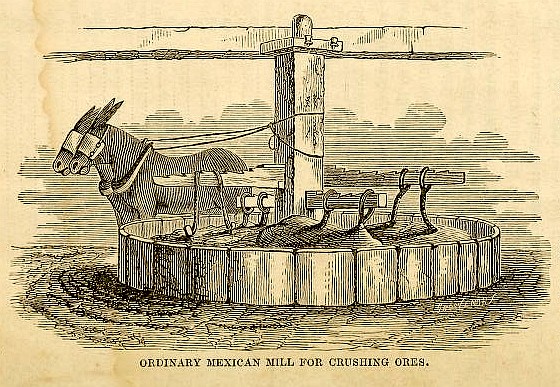

The Sonora Exploring and Mining Company’s 1857 promotional brochure clearly overstated its resources and promise. Finding shareholders during a year of economic panic was difficult enough, but effectively mining the area at any time would have required extraordinary improvements in tangible infrastructure, and large, agile regiments of cavalry and attendant livestock for defense. Several field administrators for the mines would no doubt have preferred the usual risks of bankruptcy or prison in failure, over having their lives taken.

We wish we had a response to the pamphlet from the 140 or so migrant barreteros and tenateros, who were paid through credits at the overpriced company stores — when they were paid — and had to fight American filibusters and Pinal, Gileño, and Chiricahua raiders both in Arizona’s mines and at home across the Sonora line. Herman Ehrenberg’s 1858 Map of the Gadsden Purchase locates many of their familiar towns. And the campaign to find investors did provide work for illustrators.

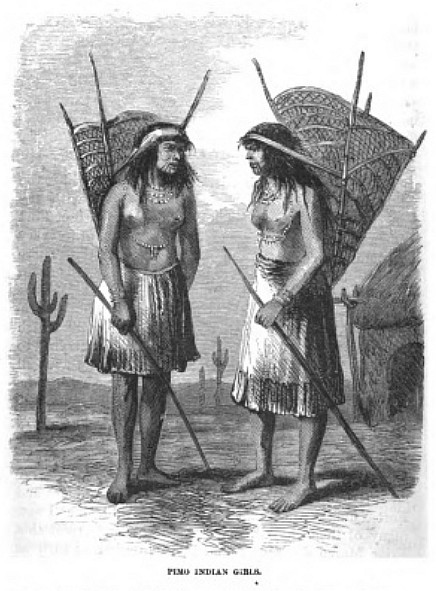

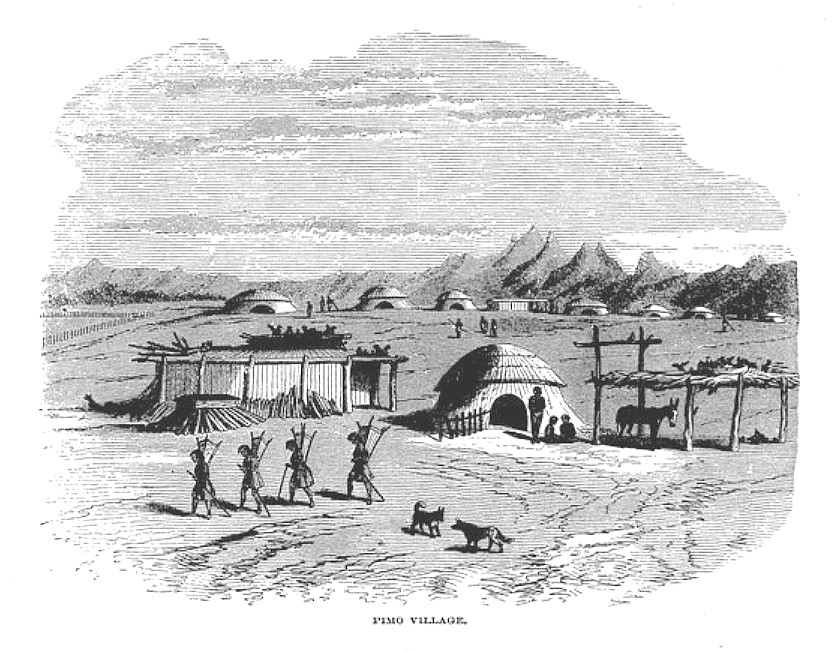

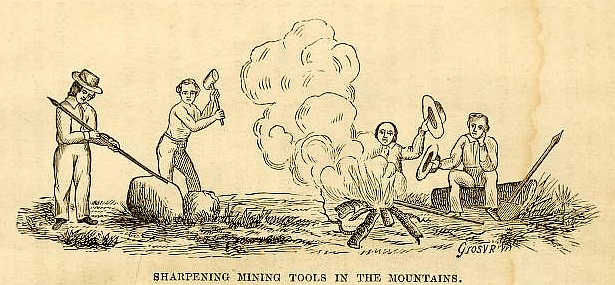

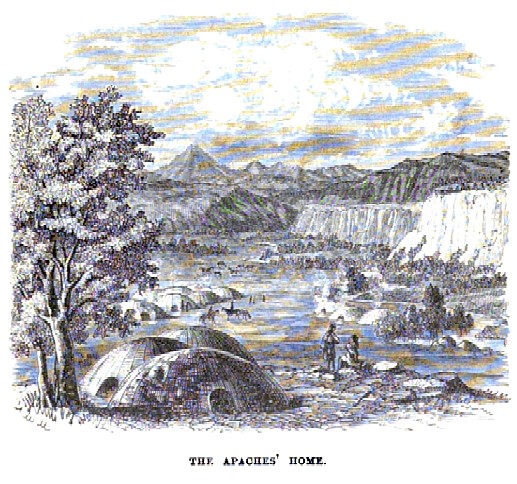

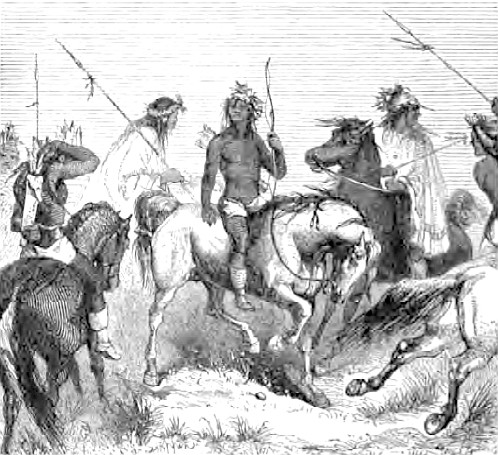

Samuel Woodworth Cozzens, author of boys’ frontier novels, affordable attorney, and pal to fugitives like Ned McGown, is a lively witness in Explorations & Adventures in Arizona & New Mexico . . . (1873; facsimile reprint, Secaucus: Castle, 1988). His homespun anthropology gets a bit ambitious, and his engravings often seem caricatures — yet both provide useful information.

Cozzens presents this village, for example, as a permanent encampment of Mangas Coloradas.

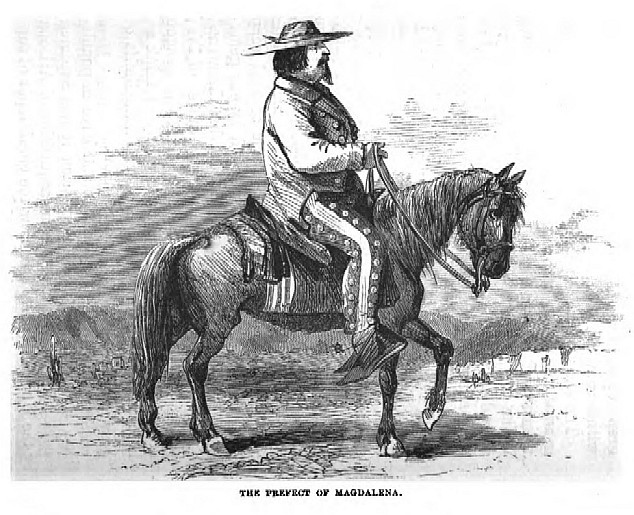

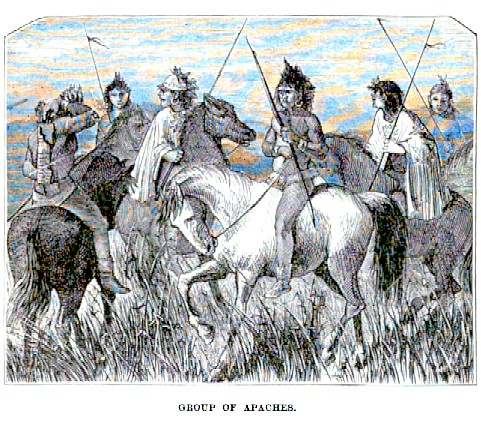

We thought this romantic tableau was familiar when we found it in Cozzens, but we could have been recalling Bartlett, where we found the same horseman reaching for his quiver and other similar figures positioned differently. Who borrowed it from whom, or are they both derived from a common source?

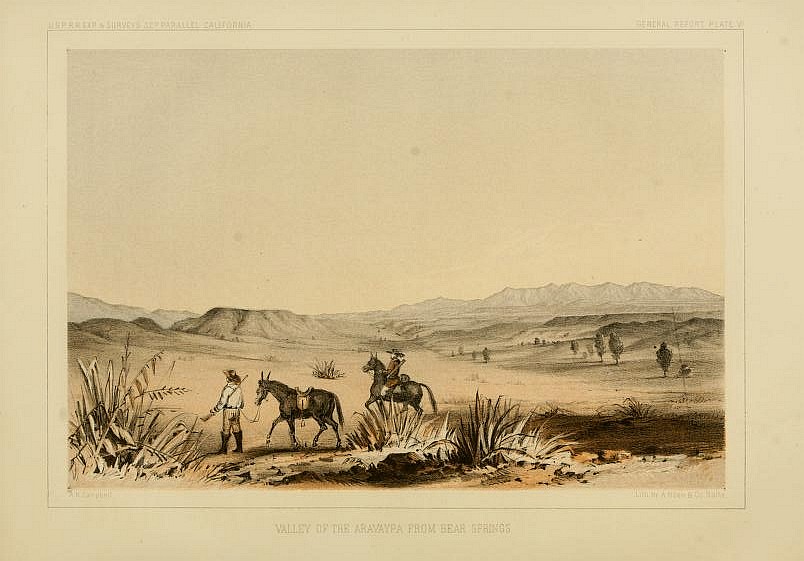

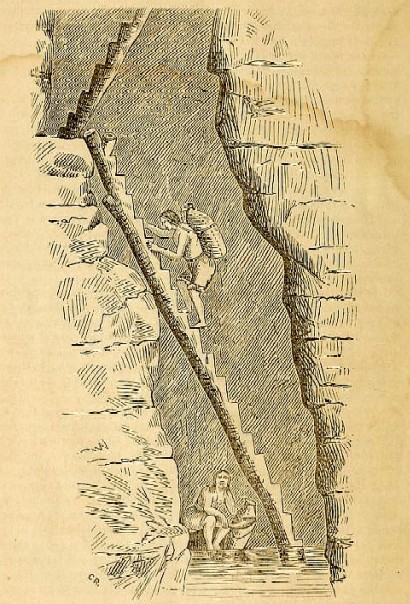

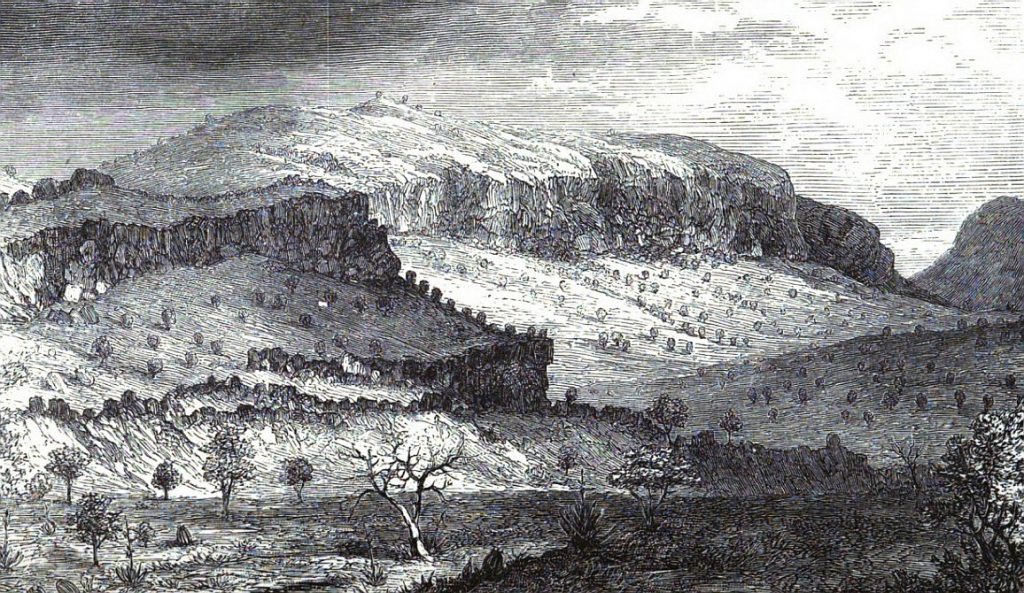

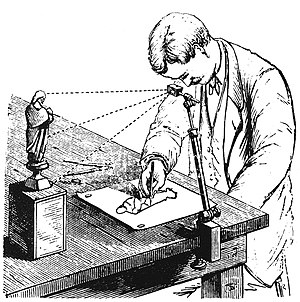

The distinct lines of this sketch display the use of a camera lucida. In recounting his search for the site of the Seth Eastman watercolor ‘Great Canyon Rio Gila’, cartographer Tom Jonas describes the technology surveyors used to produce precise field drawings, from which lithographs like ‘Great Canyon’ were later rendered: https://truewestmagazine.com/article/finding-the-great-canyon-on-the-gila-river/.

In transforming cartoons into watercolors, artists applied rich tones like these:

Rhode Island School of Design Museum curates an impressive collection of Eastman’s watercolors, which brought texture to field drawings of the Gadsden Purchase.

Nearly a decade into this project, we discovered that someone else had a similar idea. Twice. In 1968, Robert V. Hine published Bartlett’s West: Drawing the Mexican Boundary (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1968; LCCCN 68-13910), presenting the railroad survey art of John Russell Bartlett and Seth Eastman; and in 1996 the Albuquerque Museum organized an exhibit of boundary survey artists, adding Henry Cheever Pratt and others to the list — Drawing the Borderline: Artist-Explorers and the U.S.-Mexico Boundary Survey (Albuquerque: the Albuquerque Museum, 1996; ISBN 0826317529, LCCCN 96-83034). Scholars for the exhibit shift credit for some of the works Hine thought were made by Pratt to Bartlett and others. Since some draughtsmen’s sketches were collective projects, it’s often difficult to know whom to credit, so attribution can be fluid and subject to change as more information is found. Readers may find these books helpful. Both the Albuquerque exhibit catalog and Hine’s book can be found for less than forty dollars.