Like Solomon Warner, Richard Ewell was the grandson of a Revolutionary War veteran. His maternal grandfather, Benjamin Stoddert, had served as a cavalry major in the Continental Army, and after suffering a serious wound in the 1777 battle of Brandywine withdrew from field duty to continue his service as secretary of the Board of War. In 1798, John Adams appointed Stoddert the first Secretary of the Navy and, later, Secretary of War. President and Abigail Adams were frequent visitors in the Stoddert’s Philadelphia home. James and Dolley Madison had been guests at the wedding of Ewell’s parents, Thomas Ewell and Elizabeth Stoddert, in Georgetown, Washington, D. C. Thomas studied medicine under Benjamin Rush at the University of Pennsylvania, and — with the help of his father’s former classmate at the College of William and Mary, Thomas Jefferson — received an appointment as surgeon in the U.S. Navy.[i]

But Dr. Ewell proved to be a rather eccentric physician and author, and a poor provider. Within thirteen years of his marriage, the family fortunes declined so much that the Ewells were obliged to move to an isolated family property in Prince William County, Virginia. In that short span of time, they went from living in one of the grandest homes in Georgetown — a center of commerce, culture, and government administration — to a rural estate plagued with rocky soil. The family had optimistically named the property Belleville, beautiful farm, but its nickname of Stony Lonesome may have been more appropriate. There, several years of Dr. Ewell’s erratic behavior, depression, and alcoholism, and the family’s increasing poverty, took its toll. In 1824, he published The American Family Physician, but the book’s popularity did little to improve the family’s situation. When Dr. Ewell applied for a teaching position at the University of Virginia’s medical school, his letters to Thomas Jefferson and James Madison requesting recommendations apparently went unanswered. His alcoholism and unreliability were, by then, well known. He died two years later, at the age of forty, leaving Elizabeth, nine-year-old Richard, and seven other children without even a poor provider.[ii]

Determined to overcome her predicament, Elizabeth consoled the children, reminded them of their distinguished heritage, and set to work. She found a position teaching school, and the boys managed the farm. Soon Benjamin won an appointment to the U.S. Military Academy at West Point, while Paul began attending medical lectures at Columbia College in Washington. Rebecca was sent to live with relatives in Maryland, and found work teaching music. The last male standing, young Richard, began to regard himself the man of the house — a role his older sister Elizabeth thought he took far too seriously. Richard appeared to have inherited at least some of his father’s troubling behaviors — eccentricity, a violent temper, “nervous energy,” and a fondness for alcohol. Still, some found him intelligent, practical, and free of the excesses his father suffered.[iii]

When she was back at Stony Lonesome, Rebecca taught Richard to read and write, and schooled him using their father’s large library, despite her misgivings. At the age of seventeen, he was sent to friends’ homes to study formally for a year. Searching for further opportunities for the boy, mother Elizabeth began to ask for recommendations for his appointment to West Point. The military academy not only offered a good education in the sciences and engineering, but would set Richard on a respectable career path as an officer. There were no tuition fees, and cadets even received a small stipend for personal expenses. Following in his brother’s footsteps seemed an ideal solution for Richard.

As a descendant of a Revolutionary War hero and cabinet member, in a family that clearly did not have the means to otherwise provide him with a college education, Richard certainly met the qualifications. Drawing on all her family’s considerable resources, Elizabeth secured a meeting for her son with President Andrew Jackson, and Jackson wrote a recommendation for him. After securing a second recommendation from their congressman, the Ewells’ two-year campaign to get Richard into the academy finally succeeded. Elizabeth signed her consent for his five-year enlistment, and the nineteen-year-old packed his bags and headed for West Point in June 1836.[iv]

At West Point, Richard was happily reunited with his brother Benjamin, who had stayed on after graduation to teach mathematics. The two looked so much alike that the instructor was at least once mistaken for the plebe. By the end of September, though, Ben moved to York, Pennsylvania to work as an assistant engineer for the Baltimore and Susquehanna Railroad. When he was close to graduation, Richard wrote his brother, remarking “I have no particular wish to stay in the army but a positive antipathy to starving or to do anything for a living that requires any exertion of mind and body.” He was certainly understating the “amount of exertion” good soldiering would require but, more importantly, he was also underestimating his own capabilities and ambition, and dismissing the possibility he might actually enjoy military life and make a good soldier.[v]

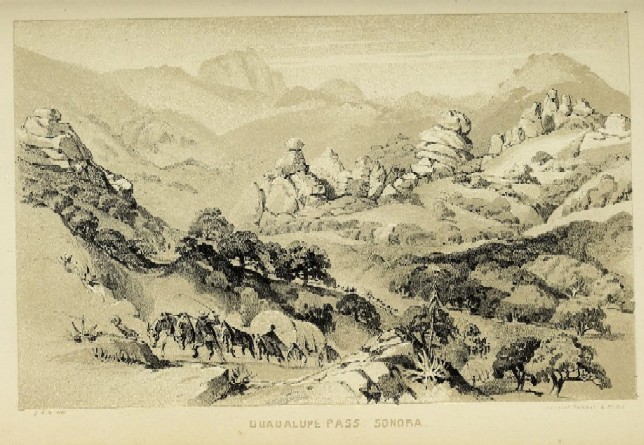

Three months later, on July 1, 1840, Richard graduated thirteenth in his class of forty-two cadets — seven slots behind William Tecumseh Sherman, and was brevetted a second lieutenant in the First Dragoon Regiment. Rebecca’s tutoring and his sole year of formal education had served him well. Now, sixteen years after his graduation from West Point — and deployments in Indiana, Kansas, and Cherokee Territory; escorts for traders on the Santa Fe Trail, and generals and governors throughout the frontier; service in Mexico during the Mexican-American War, where he buried a brother and a cousin; and as a post commander at Los Lunas, New Mexico Territory — a seasoned, if reluctant, officer found himself in a challenging post on the Gadsden Purchase frontier.[vi]

[i] Elizabeth Stoddert’s great-great-grandfather, Benjamin Tasker, had served as president of Maryland’s Proprietary Council for two decades, and three of her great-uncles as governor and provincial secretaries. Richard Ewell’s paternal grandfather, Jesse, had been a colonel in the revolutionary militia — although it is unlikely he ever saw combat. Donald C. Pfanz, Richard S. Ewell: a Soldier’s Life (Chapel Hill and London: University of North Carolina Press, 1998), 2, 4, 5, 8-11, 505, 506. Samuel J. Martin, The Road to Glory: Confederate General Richard S. Ewell (Indianapolis, Ind.: Guild Press of Indiana, Inc., 1991), 3.

[ii] Pfanz, 4-8. Samuel J. Martin, 3-4.

[iii] Pfanz, 11 (quote), 12. Pfanz contends Richard was regarded relatively normal because inbreeding had brought most Ewells of succeeding generations “a certain imbalance of mind.” (12) Samuel J. Martin, 4.

[iv] Pfanz, 13-14. Samuel J. Martin, 4.

[v] Pfanz, 16. Richard Stoddert Ewell to Benjamin Ewell, West Point, March 29, 1840 (quote). In Percy Gatling Hamlin, ed., The Making of a Soldier: Letters of General R. S. Ewell (Richmond, Va.: Whittet & Shepperson, 1935), 33-35.

[vi] Pfanz, 26, 27, 28-91. George W. Cullen, Biographical Register of the Officers and Graduates of the United States Military Academy, 1802-1867 (New York: James Miller, Publishers, 1879), Volume I, 602. Samuel J. Martin, 5-8. Ewell’s brother, Lieutenant Thomas Ewell, was shot at close range during hand-to-hand fighting at Cerro Gordo, a pass on the National Highway between Vera Cruz and Mexico City, during the Mexican-American War. Levi Gantt, a cousin, came across Richard during the second day of battle on the morning of April 18, 1847, and told him of his brother’s condition and location. Richard found Thomas in a great deal of pain: the ball had entered his abdomen near the navel, and was lodged close to his spine. He was obliged to lead his dragoons in pursuit of the enemy, so he left Thomas with his men for a time, but returned in the evening and was at his side when he passed between 1:00 a.m. and 2:00 a.m. that night. Richard buried Thomas the following day, and wrote their mother three days later to inform her of his death. Five months later, just outside of Mexico City, Lieutenant Levi Gantt met Richard again. But this time his bad news was more personal. He told his cousin he had volunteered for a dangerous mission, the storming of Chapultepec Castle, and feared he would not survive. He bade Richard farewell and asked him to take care of his final affairs — should that be necessary. His fear turned out to be well-founded: within a few hours of their meeting, Levi too was dead. General Winfield Scott marched into Mexico City’s Grand Plaza the following day, and claimed victory after a six month campaign. The next day, September 14, Richard recovered Levi’s body and interred it in the churchyard of Tacubaya. Richard Stoddert Ewell to Elizabeth Ewell, Jalapa, Mexico, April 22, 1847. In Hamlin, ed., 64-68. Pfanz, 50-52, 56-57.