Abandoning his search for pack stock and hardware at the end of March 1856, Solomon Warner left Rodolfo Spense in charge of his Tucson store, hired a man named Fox, and joined a Rio Grande emigrant train bound for California to return to Yuma Crossing. He knew that his business partners, Hooper and Hinton, had used mule teams to transport their goods overland to Arizona before the advent of steam shipping on the Colorado, and he wanted to talk to them about mules. After briefing them on events in Tucson and striking a deal, Warner headed to a San Diego ranch to retrieve a dozen of the sutlers’ large California mules, and drive them to Yuma toward the end of May.[i] But he hadn’t been able to find any wagons or harnesses in California, nor anywhere along the Colorado. In desperation, he finally gave in to the suggestion of some Sonoran packers that he use aparejos, pack saddles, as they did, and purchased a dozen aparejos in the area of Yuma Crossing. Finally equipped with his own stock and packing gear, Warner left Yuma with new wares for his Tucson store on June 5, 1856, and arrived in the old pueblo on the lucky date of June 23 — the eve of the Feast Day of Saint John.[ii]

Warner might well have seen bonfires on his arrival, as they were often lit the night before el Día de San Juan Bautista as a prelude to festivities. Saint John’s Day was celebrated throughout the world in remembrance of John the Baptist, but the saint’s day had particular importance to Hispanics in the arid Far Southwest and Northern Mexico due to Saint John’s association with water. In addition to honoring the charismatic rabbi who fasted on locusts and honey, and baptized Jesus of Nazareth, many celebrants would petition John to remind the Almighty that rain was needed for the crops. As the monzón season usually began in early July, when the Fiesta de San Juan was winding down, petitioners’ prayers were frequently answered.

But the holiday in Tucson wasn’t merely a saint’s day. It was also a secular celebration with drinking, dancing, gambling, and commerce — and this was not lost on Solomon Warner. Hundreds of visitors from distant settlements traveled to Tucson to trade, barter, and join the festivities, and Warner arrived just in time to restock his store for the event. He modestly noted, “There was but little left of the old stock of goods. After a few days rest it was harvest time. Traid was good. I Concluded to have a New Stock of goods here before the feast of San Auguesteen August 28th.” His hard work and $2,300 investment had paid off, and he would be back.[iii]

After hiring Nelson Van Alstine as foreman for his twelve-mule pack train, Warner left Tucson in mid-July to resupply in Yuma, and returned to the old pueblo in ample time to set up for the Feast of Saint Augustine.[iv] Warner recalled there were many Sonorans in town and sales were encouraging, so encouraging that Warner decided to invest a share of his profits in infrastructure. And this time he had better luck finding what he was looking for — four more mules and all the freighting hardware needed to expand his train by a third, at a cost of $348. He got the mules from Pete Kitchen at the bargain price of two hundred dollars, he speculated, because “it would not take them long to eatoff their heads at a much hierprice to Keep them from being stolen by the Apacha Indians.”[v]

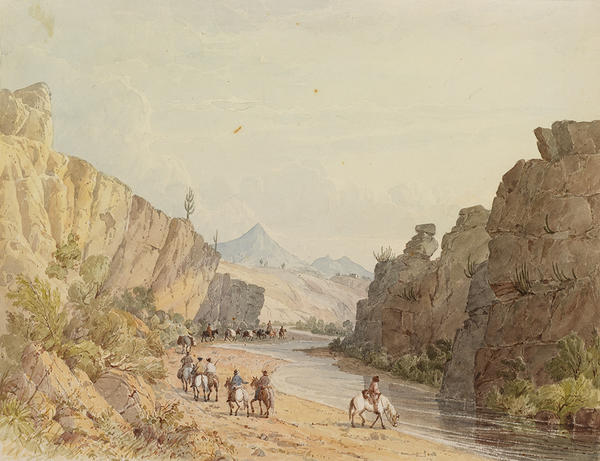

Warner left Nelson Van Alstine at the Tucson store and hired John W. Davis as the train foreman, a young Teofilo Burruel as herder, and four other Mexican Americans as packers, and headed out for Yuma around the first of October with his now sixteen-mule train, an extra mule for camp equipment, and twenty-three horses.[vi] Four days later they departed Maricopa Wells in the evening, crossing forty-five miles of “the little desert” to reach Gila Bend around eight o’clock in the morning, and pitched camp on a sand bar by the bank of the Gila River. It was there, on October 6, 1856, while they were taking their breakfast and unwinding from the long night’s journey, that an assault began.

Before they were aware of what was happening, Apache raiders had gathered all their pack mules and horses, driven them across the river, and collected them on a high hill. The seven men in the pack train quickly assembled breastworks for defense—using saddles and aparejos to hinder the expected attack from the riverbank behind them. But, while they could see the Apaches on the hill across the river with their animals throughout the day, the anticipated fight never materialized: the Apache had what they had come for, and went on about their business. When nightfall finally arrived again, and it appeared safe to do so, the men loaded what equipment they deemed necessary on the lone remaining animal, the extra mule used to haul camp gear, and set out for Yuma on foot.

While Solomon Warner noted that “the Property lost at Gila Bend Drove and carryed off by the Apacha Indians it cannot be estimated in dollars and cents for the reason there is no Pack Train in Yuma, Tucson, or any Place in the Territory that Could be bought for any price,” he would later estimate the value of his thirty-nine animals and packing gear to be $2,284 in a depredations claim he would file with the United States government. But without batting an eye over the considerable loss he’d just incurred in his first encounter with raiders, the Easterner searched out Joaquín Quiroga in Yuma, and when he found him, struck another deal to lease Quiroga’s train at the same rate he’d paid in February, $30 per cargo. It meant starting over from scratch, but he was determined to quickly restore freighting to the growing market in Tucson: Solomon Warner was back in business.[vii]

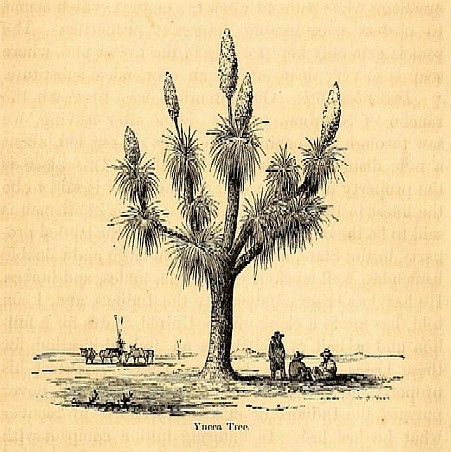

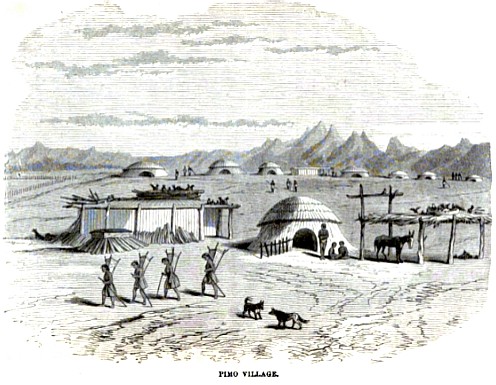

After transporting a load of goods to the old pueblo on Quiroga’s mules, Warner picked up a passenger named Fred Nevil, and returned to the Pima Villages to trade with the Pima for grain. Antonio Azul — leader of the confederated Gila River tribes — stored Warner’s grain in large arrowweed baskets that held between five hundred and fifteen hundred pounds — so heavy that, once filled, they could not be moved. While at the Pima Villages, Warner ran into Major George A. H. Blake with three companies of the First Dragoons as they rested on a journey from New Mexico to California, and supplied them with enough of his stored grain to make it to Yuma. It seems likely that Blake would have let Warner know that another four companies were on their way to Tucson to help maintain public safety. The Tucsonans’ request for American military protection was about to be met.[viii]

Two hundred and eighty dragoons under the command of Major Enoch Steen arrived at Mission San Xavier del Bac on November 14, 1856, having traveled some 340 miles from Fort Thorne since October 19. With them was an armada of freight wagons, perhaps two hundred cattle, and camp followers.[ix] Steen’s specific instructions had been to proceed to the Tucson presidio, and if the property was not privately owned, to repair and occupy it. But Steen judged the garrison’s cottages, huddled under the presidio walls, “miserable huts, unfit for use taken in the best condition,” and saw few prospects for pasture and grain in the area.

He began looking sixty miles to the south, by Sonoita Creek near Calabasas, for a more suitable garrison site, and two weeks later marched his troops and entourage to a spit of land at the junction of Portrero Creek with the Santa Cruz, across from the old mission visita near Calabasas and the mouth of Sonoita Creek. After establishing Camp Moore, Steen began negotiating with Sonoran merchants and teamsters to supply the camp with grain, beef, and other supplies from Mexico. There was ample water and pasture in the area, but lumber would need to be milled and delivered for construction. Americans began to settle near the new military camp, and apply for contracts to supply lumber and winter forage — as well as grain, beef, and other supplies.[x]

The family of Felix Grundy Ake and Mary B. Raines Ake were fairly typical settlers. But what was different about Grundy is that he had been a man of some substance before his emigration from the Vache Grasse country, south of Fort Smith, Arkansas. He had operated a mill on Vache Grasse Creek, had built one hundred forty miles of road between Fort Smith and Little Rock on contract, and — according to a son — had owned sixty-two slaves. He also owned properties in Kentucky, Tennessee, and Texas, and was wealthy enough to bet on horses he raised for racing. In Arkansas, the Akes had grown wheat, corn, oats, millet, and Hungarian grass, had raised sheep for wool, and had grown cotton, which Mary and some of the slave women spun into cloth and fashioned into clothing. In 1849, Grundy caught the gold fever and set out for California with his eldest son, Napoleon Rock, his adopted sons the Peyton boys, and two hundred cattle. After a few years prospecting, he left Napoleon Rock and the drovers tending the herd on the Russian River, and returned to Arkansas to collect his wife and six other children.[xi]

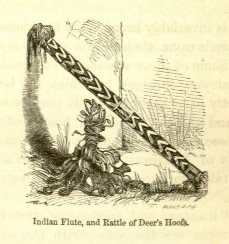

Grundy sold and bartered away his Arkansas properties until he had assembled another herd of five hundred cattle, three bull wagons with two yoke of steers each, and a Concord buggy, then headed back to California with his family in the spring of 1853, passing through Southern Arizona en route. They had some musical instruments with them — a banjo, a fiddle, and a mouth harp — for entertainment, and Mary sang some Scottish songs, such as “My Country Thou Sad and Forsaken,” while Grundy favored Irish songs such as “Tim Finnegan” and “Barney O’Brien,” and all chimed in for “Oh, Susanna,” “The Arkansas Traveler,” “Sweet Betsy from Pike,” and “Die in California.”[xii]

Their destination was a creek in the Sierra Nevada foothills above San Joaquin Valley, possibly near the mining camp of Sonora. Curiously, Grundy built his two-room cabin of picket poles, just like the jacales in Arizona, but added weather-boards, a dirt roof, and a rock fireplace in a corner of one room. Once settled in, Ake panned for gold in the creek above the cabin, and occasionally hunted beaver for the family larder, but before long it became apparent that a lawless and violent California mining camp was not the best place to raise young children. Grundy’s son Jeff relates the following incident:

“Nobody liked the Chinese very much, I reckon. It was just before we went to San Francisco [in 1854] that we had heard about the killing of Bob Cloud and his gang of Chinamen on Kern River. The Peyton boys had been up there a while with Cousin Bill Ake when Cloud brought in a bunch of Chinamen to work his claims. The miners never did like this, and on Kern River a bunch of ‘em got together and killed ‘em off, Cloud too. John Page told us afterward that Bill struck a match — one of them old California sulphur matches — on Cloud’s forehead to see if he was dead.”[xiii]

Jeff Ake did not say whether his sixteen-year-old cousin William W. Ake, twenty-year-old John Page, or the Peyton boys had actively participated in the murders.[xiv]

Grundy began to notice newspaper articles, written under the pen name “Kino,” which praised the Santa Cruz Valley in the Gadsden Purchase. There was plenty of water and forage, Kino wrote, mineral wealth looked promising, and it was just a matter of time until a railroad would be built nearby. If one could keep the marauding Apaches at bay, the area offered a great deal of promise. So, after a few years, Grundy Ake once again packed up his family and all his worldly possessions — mostly three hundred head of cattle — and formed a train with the Ashworth, Wadsworth, and Thompson families and headed out for the Santa Cruz Valley, leaving Napoleon Rock Ake and the Peyton boys in charge of his Sierra foothills cabin and the remaining cattle. Shortly after his arrival on the Santa Cruz, he contracted with the army to supply forage to Camp Moore, the predecessor of Fort Buchanan, and began freighting in supplies from Sonora, using mules and aparejos, and sometimes wagons. He did some farming, began raising hogs, and even sold whiskey to the soldiers — an appropriate distance away from the military camp — when he could get it. But then his nephew Bill showed up from California with John Page and two dozen other men, whom trouble seemed to follow.[xv]

Encouraged by William Walker’s invasion of Nicaragua, San Francisco politician Henry A. Crabb embarked on a filibustering expedition of his own into Sonora in 1857. Crabb’s wife was from the wealthy Ainza family of Sonora, which had lost much of its land and fortune in the civil war of the previous year, and his brothers-in-law in Sonora had convinced Crabb to help Ignacio Pesqueira overthrow Governor Manuel Gándara in the ongoing turmoil in that state. Crabb’s reward was to be extensive land grants and mining rights on the border with the Gadsden Purchase, and Pesqueira hoped Crabb’s Arizona Colonization Company settlements would act as a buffer against Apaches who habitually crossed the boundary line to raid Sonora.

In late January 1857, Crabb’s militia of ninety men took a steamer from San Francisco to San Pedro, California, then marched overland to a spot east of Yuma, now called Filibuster Camp, where they practiced drills for a time. They then advanced farther in the Gadsden Purchase and split into two groups — a band of twenty, which remained in Tucson, and the larger force of seventy, which advanced toward the boundary line. The main body of Crabb’s mercenary army — a considerable force of one thousand — was supposed to sail directly to Sonora from San Francisco, then march overland to Altar and join Crabb. But it never materialized. Meanwhile, Pesqueira defeated Gándara on his own, and notified Crabb by official dispatch that he would no longer be needing the Americans’ assistance. Having already gained control of the state, the last thing he wanted was to be perceived as welcoming American interlopers.

Crabb, however, audaciously informed Pesqueira that he and his army of seventy intended to proceed as originally planned. In Sonoita on March 26 Crabb repeated this in a letter to José María Redondo, Prefect of the District of Altar, announcing “I have come with the intention of injuring no one; without intrigues, public or private,” and decrying Sonora’s preparations to repel him by force. Seizing the opportunity, Pesqueira then issued a conveniently patriotic call to arms: “Sonoreños, let our conciliation become sincere in a common hatred of this accursed horde of pirates, destitute of country, religion or honor.” By the time the Americans marched into Caborca on April 1, the Pesqueira army and Sonoran citizenry were ready and waiting to respond.[xvi]

The Americans fired the first volley; the Mexicans fired back, then took positions behind the walls of the mission Nuestra Señora de la Concepción. The filibusters found cover in some buildings across the town plaza and exchanged fire with the soldiers for nearly a week, but half of them were killed and most of the survivors wounded, so they accepted an offer of a fair trial in return for their surrender. The fair trial never occurred. After they laid down their arms, all but a fourteen-year-old boy were executed. Crabb was decapitated, and his head placed on display. When the smaller band of twenty filibusters finally arrived, under the command of Tucsonan Granville Oury, they walked into a hornet’s nest of nationalist fervor. The Sonorans quickly surrounded the would-be warriors, and the Tucsonans were barely able to effect a retreat — lucky to lose only one of their party.[xvii]

Bill Ake, John Page, and the others arrived at Filibuster Camp too late, despite their enthusiasm, to join Crabb’s half-baked adventure, and made it to Tucson too late to accompany even the twenty who had formed the second excursion. But, determined to avenge the deaths of Crabb’s men, they and other filibusters from Tucson traveled toward the boundary line, where they killed several Mexicans and Indians before they, too, were forced back across the border by outraged Sonorans. They then began terrorizing Hispanics in Sonoita Valley, and even threatened some Mexican laborers who were out cutting hay on Grundy Ake’s farm. Grundy roundly chastised his nephew and the murderous rabble for abusing his laborers — and the killings on the border and their bad behavior on the Sonoita earned the filibusters a reputation as outlaws and murderers. Grundy must have harbored some hope for John Page, however: he hired Page as a driver to haul contract lumber from the Santa Ritas to the military post, and even allowed his young sons to ride with him.[xviii]

Forty-eight-year-old widower Elias Pennington arrived in the Sonoita Valley in June 1857 with eight daughters and four sons. Born in South Carolina, Pennington had much in common with Grundy Ake and other early Arizona settlers: he had wandered a bit before arriving in the Gadsden Purchase, and he anticipated his stay there would likely be temporary. His first four children were born in Tennessee, outside of Nashville, and the last eight in Honey Grove, Texas. When his wife suffered an illness following the birth of their twelfth child, and died ten months after Sarah was born, Pennington again packed up the family and moved them one hundred fifty miles southwest to Jack County, Texas, where they set up a new farm. After just a year and a half in Jack County, Pennington again got the wanderlust when he heard of a wagon train headed for California, and decided the golden state might hold more promise for him than Texas. He packed up his family again in the spring of 1857 and joined the California-bound train.

By around June 1, they had safely made it to the San Pedro River crossing, but twenty-year-old Larcena, Pennington’s third eldest, had come down with “mountain fever,” a debilitating and potentially fatal disease characterized by cycles of high fever, body aches, delirium, and even unconsciousness. To make matters worse, by June 5 or 6 when they reached Fort Buchanan, several of Pennington’s animals had given out. Elias decided they should leave the road and recruit in the Sonoita Valley so Larcena might recover her health. It had been less than two years since his wife Julia had passed, and continuing on could put Larcena’s life at risk. California would still be there after she was well again. Pennington found an unclaimed piece of ground on Sonoita Creek, and moved his three wagons and cattle down to it and set up camp. It must have appeared Larcena’s recovery was going to take a while, as he built a jacal out of willow branches for shelter, and secured a contract to cut and deliver wild hay to Fort Buchanan.[xix]

Three weeks after the Penningtons’ arrival on the Sonoita, Sonoran merchant Francisco Padres was returning home after delivering a shipment of corn to Fort Buchanan. About a mile south of the boundary line, five Americans attacked Padres’s pack train, killing three of his seven mule-skinners, or arrieros, and taking all forty-five mules to the outskirts of Tucson. When news of the assault reached Fort Buchanan, Major Steen dispatched Col. Sharp and a party of soldiers, accompanied by Granville Oury and other civilians on chase animals provided by Solomon Warner, to recover the mules. They managed to locate the band and retrieve thirty-six of the animals and aparejos, and arrest two filibusters named Davis and John G. “Billiard” Ward — who had arrived with John Page and Bill Ake’s group from California — for the murders, although Davis somehow escaped before they reached Fort Buchanan. The remaining murderer was safely delivered to the stockade, but as there was no criminal justice infrastructure yet in place, and “as the military officers at the post hesitated about assuming jurisdiction in the premises,” Ward was soon released.[xx]

Solomon Warner had been able to catch Major Steen’s troops before they left San Xavier del Bac for Calabasas in late November 1856, as he recalled purchasing an old freight wagon and a harness from some of Steen’s freighters in Tucson. After repairing the equipment and acquiring eight mules, Warner had left the old pueblo for Yuma February 1, 1857, returning with a load of goods for his empty store in the middle of March — about the same time Crabb and Gravnille Oury’s filibusters were getting routed in Sonora, and Bill Ake and other Tucson filibusters were murdering Mexicans and Indians across the border and terrorizing the Sonoita. Back in Tucson, Warner had picked up another light wagon and four more mules, and when reloading on the return trip from Yuma, he made sure to bring beads, trinkets, and other appropriate goods to trade with the Pima.

As the road between the Pima Villages and Tucson was comparatively firm and level, he found he could add 25 percent more cargo for this final leg of the trip. Warner knew there was a ready market for Pima flour and pinole in the Old Pueblo, but he’d had to wait a few days while it was ground, then he’d loaded up all his wagons and mules could handle, along with some buckskins and coreates, water-tight willow baskets shaped like tin pans, and headed south. In Tucson again by May 20, Warner found another old wagon and harness, and eight more mules. He stayed long enough to loan some of his mules to the chase team to help capture two of the murderers of Francisco Padres’s arrieros and recover his stolen pack train. After repairing his new gear and assisting with trade during the Feast of San Juan, he left with his newly configured train of two eight-mule teams and one four-mule team hauling three wagons.[xxi]

The day following the Feast of San Juan, as Warner was preparing to travel north again on the long jornada toward the Maricopa Villages, a row of army officers stood on a hill overlooking the Gila Valley some ninety miles northeast of Tucson, their field glasses focused on the fifteen-mile-wide river plain a thousand feet below, searching for Apaches. Colonel Benjamin Bonneville had dispatched them to the valley in response to settlers’ increasingly strident complaints about Indian raids — and the murder of Navajo agent H. L. Dodge by a native, which had caused some concern in the department. But reviving his reputation as an Indian fighter may have been another incentive for Bonneville. Washington Irving had immortalized him in the popular 1837 book, The Rocky Mountains: or Scenes, Incidents, and Adventures in the Far West, digested from the Journal of Captain B. L. E. Bonneville, and Bonneville’s temporary command of the Department of New Mexico gave him a unique opportunity to demonstrate he still had some soldierly skills.

The Gila Campaign was ambitious, to say the least, with troops simultaneously deployed on three fronts in a coordinated strike meant to cow raiding Mogollon, Gila, and Chiricahua Apache bands into submission. Colonel W. W. Loring led a column of three hundred men from Albuquerque in the north to the headwaters of the Gila, in Mogollon country; Lieutenant Colonel D. S. Miles targeted the Gila Valley with two hundred and eighty out of Fort Thorne in the southeast; and Major Steen was to march from the newly-established post on the Santa Cruz into the Chiricahua Mountains with a third column of one hundred twenty dragoons.[xxii]

While the post near

Calabasas called Camp Moore had already acquired the name Fort Buchanan, it was

in the process of being relocated: angry that Major Steen had ignored his

initial order to set up the post in Tucson, Col. Bonneville had issued Steen a

second order to move it there. But Lieutenant Milton Carr had still been unable

to find a suitable site in the Tucson-San Xavier area, so Captain Richard Ewell

was sent to search the area between the Santa Cruz and San Pedro Rivers. The

site Ewell found, with plenty of water and fertile soil for pasture, was at

Ojos Calientes, twenty-five miles northeast of Calabasas at the head of Sonoita

Valley — a location that would prove to be less than ideal. In a portent

circumstance, the major became so ill with malaria that he was unable to lead

his column into battle, and dispatched Capt. Ewell in his stead.[xxiii]

Enter government by taxation in the search window to continue.

[i] Solomon Warner, “Claim of Solomon Warner for Indian Depredations, Property taken and destroyed and Wounds received,” July 21, 1890, 4-5, Solomon Warner Family Papers (1859-1951), MS 844, Box 3, folder 45, Arizona Historical Society, Tucson (AHS).

[ii] Warner, “Claim,” 5-7.

[iii] Saint John’s Day is widely celebrated throughout the northern hemisphere. In Nordic and Baltic cultures, for example, it is known as Modsommar, Midsomer, or Midsummer; in the Russian Federation it is called Ivan Kupala Day. Tucsonenses called the windswept squalls of the monzón season chubascos. Mariano Velásquez de La Cadena, Velásquez Spanish and English Dictionary (El Monte, California: Velásquez Press, 2007). James H. McClintock, Arizona — Prehistoric, Aboriginal, Pioneer, Modern, vol. 2 (Chicago: S. J. Clarke Publishing Co., 1916), 546-47. James E. Officer, Hispanic Arizona, 1536-1856 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1987), 147, 366n40. Warner, “Claim,” 7. Solomon Warner’s longhand document lacks punctuation, which makes it difficult to read. It has been slightly amended here, and in future quotes, with punctuation. A literal transcription would be “[T]her[e] wa[s] but little left of the old stock of goods[.] [A]fter a few day[s] rest it was harvest time[.] [T]raid was good. I Concluded to have a New Stock of goods here before the feast of San Auguesteen August 28th.”

[iv] Warner, “Claim,” 8. Van Alstine, forty-one years old and a New Yorker by birth, had arrived in Tucson in January. The 1860 census would find him counted as a farmer in the lower Santa Cruz Settlement near Tubac, living with twenty-four-year-old Rita Campo, two-year-old Antonio Van Alstine, fifteen-year-old Ramón Rosario, and five-year-old José Romero — next to the young blacksmith Antonio Comadurán and his family. Officer, Hispanic Arizona, 282. Decennial U.S. Census (1860), County of Arizona, New Mexico Territory; Lower Santa Cruz Settlement Division, 52; enumerated on September 11, 1860.

[v] Warner, “Claim,” 8. Warner was no doubt referring to the common understanding that mules had to be penned, fed, and guarded if they were to be kept at all — a costly proposition; in pasture, even tethered or hobbled animals were easy prey for Apache raiders. Officer places thirty-three-year-old, Tennessee-born Peter Kitchen in Canoa in March 1856, and the 1860 census would find him a few doors away from Nelson Van Alstine in the lower Santa Cruz Settlement, listed as a farmer living with twenty-six-year-old Jesus[a] Mendoza and eight-year-old Eduardo Mendoza. Officer, Hispanic Arizona, 282. Decennial U.S. Census (1860), County of Arizona, New Mexico Territory; Lower Santa Cruz Settlement Division, 52; enumerated on September 11, 1860.

[vi] Warner, “Claim,” 9. Warner spells his herder’s name “Tufalo Bueruel” and “Tufalo Buruel”. The drover — who would become one of Warner’s longest-standing employees — is most likely the twenty-four-year-old Tucson laborer, born in New Mexico, who is listed as “Teofilo Barruel” in the 1860 census, making him twenty years old when Warner hired him; “Teofilo Bourbel”, and may be the twenty-five-year-old Tucson laborer, born in Tubac listed in the 1864 census, although the birth date then is earlier. Teofilo is a more common given name, and Burruel a more common surname: thirty entries for Burruel can be found in the 1870 census. Population Schedules of the Ninth Census of the United States (1870), NA Publications Microcopy no. 593, roll 46, vol. 1, 1-120, NA, NA and Records Service, (Washington, D. C.: General Services Administration, 1965). Decennial U.S. Census (1860), County of Arizona, New Mexico Territory; Tucson Division, 20; enumerated on August 6, 1860. Census for the First Judicial District (1864), Arizona Territory; enumerated in April 1864 by Gilbert W. Hopkins.

[vii] Warner, “Claim,” 9-11, 23.

[viii] Warner, “Claim,” 12. Sacks, “Origins,” 213.

[ix] Benjamin Sacks, “The Origins of Fort Buchanan,” Arizona and the West 7, no. 3 (Autumn 1965), 215, 217. While Sacks lists 250 soldiers in the group, Altshuler counts 271 enlisted men, eight officers, a contract surgeon, and company laundresses, but notes that only 179 men in the four dragoon companies — B, D, G, and K — were available for military duty, as some were engaged as escorts for mail couriers and wagon trains; others were sick, on leave, or under arrest; and many were obliged to serve as teamsters, packers, cooks, mechanics, carpenters, and clerks — as the army had not yet begun to employ non-enlisted support staff to perform these operations tasks. Constance Wynn Altshuler, Chains of Command: Arizona and the Army, 1856-1875 (Tucson: Arizona Historical Society, 1981), 3, 5.

[x] Sacks, “Origins,” 214, 215, 217 (quote 218n46), 218&n46. Steen could have used another excuse for failing to occupy the presidio: at least some of the cottages were private property, awarded for service to the Crown. Pima County Book of Deeds no. 1, 24-25, free translation from the Spanish, Solomon Warner, Hayden biographical file, AHS. Deeds of Real Estate, roll no. 85.3.51, item 4, 24-25, RG 110, SG 5, ASLAPR. T. Michael Fink, “Captain Ewell’s Fort Buchanan Affliction,” Journal of Arizona History 49, no. 1 (Spring 2008): 48-49. Henry P. Walker and Don Bufkin, Historical Atlas of Arizona, 2d ed. (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986), map 14.

[xi] James B. O’Neil, They Die But Once, The Story of a Tejano (New York: Knight Publications, Inc., 1935), 2, 3, 5, 7, 8, 17-18. Felix Grundy Ake, Hayden biographical file, AHS. Vache Grasse is French for “fat cow”. On August 26, 1860, fifty-year-old F. Grundy Ake would share a dwelling with forty-year-old Mary B. Ake, fourteen-year-old Will, twelve-year-old Jeff, and three-year-old Emma — who had been born in New Mexico Territory by that date. Forming a separate family were twenty-three-year-old N. R. Ake (likely Napoleon Rock Ake — who earlier had been tending Grundy’s cattle in California), and Lil Ake, age twenty-five. Grundy Ake claimed the occupation of farmer, with $2,500 in real property and $6,000 in personal property. Decennial U.S. Census (1860), County of Arizona, New Mexico Territory; Sonorita Creek Settlement Division, 30-31; enumerated on August 26, 1860.

[xii] O’Neil, 8, 10-16, 13 (quote).

[xiii] O’Neil, 17-19, 20 (quote). For some context for the Chinese in California during the Gold Rush, see Michael Luo’s review of Mae Gnai’s book The Chinese Question in “Books: arrivals,” The New Yorker, August 30, 2021, 65-69.

[xiv] Decennial U.S. Census (1860), County of Arizona, New Mexico Territory. O’Neil, 8, 20-21.

[xv] O’Neil, 20-27. Jeff Ake told his biographer that this was in 1855, a year before Major Steen would arrive with his troops; Ake was quite young at the time, and is probably mistaken in his chronology. Virginia Culin Roberts does not mention the Ake family’s California adventure in her account, but places their arrival in the Santa Cruz Valley in early 1857, which seems more likely. William Kirkland does not include Grundy Ake among those present in Tucson when the Mexican dragoons departed in March 1856. Virginia Culin Roberts, “Heroines on the Arizona Frontier: The First Anglo-American Women,” Journal of Arizona History 23, no. 1 (Spring, 1982): 16. Kirkland (interview), Arizona Republican, June 23, 1890.

[xvi] Horace Bell, Reminiscences of a Ranger; or, Early Times in Southern California (Los Angeles: Yarnell, Caystile & Mathes, 1881), 217-20, 220 (Crabb quote). Thomas Torrans, Forging the Tortilla Curtain (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 2000), 83-84.

[xvii] Horace Bell, 221-22, 221 (Pesqueira quote). Torrans, 83-85.

[xviii] Virginia Culin Roberts, With Their Own Blood: a Saga of Southwestern Pioneers (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1992), 39-43. Although he was only twelve years old in 1857, Jeff Ake would later identify some of the late-arriving filibusters as John Ainsworth, Bill Ake, John Delaney, John Page, Bob Phillips, Alfred Scott, Cyril Scott, John G. “Billiard” Ward, old Cap’n Sharp, Poker Jack, Three-fingered Jack, Davis, Dyvelbits, McCallister, and Wilson. Jeff claimed Bill Ake had killed at least one man in California, and later killed a Santa Cruz Valley farmer from Texas named Davis, adding, “Bill had killed several men — he limped from being shot in one fight.” O’Neil, 28-31, 31 (quote). Daily Alta California, December 25, 1857. Letter of Granville H. Oury to an unknown recipient, Mesilla, May 21, 1862; and Solo (Solomon) Warner, “To the People of Arizona: The Testimony of an Old Citizen on Hon. Granville H. Oury;” in Cornelius C. Smith, Jr., “The History of the Oury Family,” 77-78, 85. Cornelius C. Smith, Jr. Papers, MS 738, Box 1, folder 10, AHS.

[xix] Roberts, With Their Own Blood, 11-21. Robert H. Forbes, The Penningtons, Pioneers of Early Arizona: A Historical Sketch ([Tucson:] Arizona Archeological and Historical Society, 1919), 1-3, 7, 10.

[xx] Daily Alta California, December 25, 1857. Roberts, With Their Own Blood, 44.

[xxi] Warner, “Claim,” 13-15.

[xxii] John Van Deusen Du Bois, Campaigns in the West, 1856-1861: The Journal and Letters of Colonel John Van Deusen Du Bois (Tucson: Arizona Historical Society, 2003), vii-ix, 25-26. For purposes of this text, the term Chiricahua Apache refers to those bands primarily ranging in the Dragoon, Chiricahua, and Dos Cabezas Mountains; Pinal Apache, those primarily ranging in the Pinaleño, Santa Teresa, and Galiuro Mountains, and Aravaipa Canyon; Tonto Apache, those from the Mazaltals and Tonto Basin; and Mimbres Apache, who could be Coyotero — from the White Mountains, Mogollon — from the eastern end of that plateau and range, Gila or Gileño — from the upper reaches of the river, or Mescalero — from other New Mexico ranges west of the Pecos River.

[xxiii] Sacks, “Origins,” 214, 220-22. Daily Alta California, December 25, 1857. The initial order to take command of the Tucson presidio had come from Commanding General of the Army Winfield Scott, and was issued on June 17, 1856. It was passed down the chain of command to Steen by the head of the Department of New Mexico, Brevet Brigadier General John Garland, on July 28, 1856. Sacks, “Origins,” 210, 211, 213.