The first westbound Butterfield Overland Mail coach arrived in Tucson at 8:30 in the evening on October 2, 1858, discharged a reporter for the New York Herald in front of the home of the widow Guadalupe Santa Cruz, and — stopping only long enough for the teams to be changed, and for the reporter to down a cup of coffee and mail a dispatch to his publisher — continued on toward Maricopa Wells and Yuma.[i]

Guadalupe Santa Cruz’s home was a nearly ideal property for the Butterfield Overland Mail Company’s station, and may have been one of the larger homes in Tucson. Located a hundred feet from the main road, La Calle Real, just around the corner from Solomon Warner’s store, across the street from Mark Aldrich’s store — which housed the post office, and next door to Ramón Pacheco’s blacksmith shop with its meteorite anvils, the Santa Cruz home had twenty yards of frontage on El Calle de Correo, as well as a wide passageway, or zaguán, leading to an interior courtyard of some twelve hundred square feet. And importantly, the presidio acequia and its tall shade trees ran only a hundred feet behind the residence, convenient for watering the Butterfield line’s draft animals.[ii]

The more substantial row houses on the desert frontier, such as the widow Santa Cruz’s, were constructed of adobe around fourteen inches thick set on a stone foundation. Window and door lintels were mesquite timbers, as were the crotch timbers for the corredor, or interior porch. The unglazed windows had wooden shutters, sometimes slatted, which opened inward. Exterior walls were plastered with lime, often tinted a light blue or buff; interior walls were plastered with mud, usually whitewashed, but sometimes also tinted. Ceilings were tall, to dissipate the heat. Roofs were built with pine rafters overlaid with saguaro ribs, which, in turn, were covered with earth graded to create valleys for the collection of rainwater, which was drained off through distinctive and sometimes decorative spouts which jutted out over the boardwalk from the top of the walls. The rear of the properties was often enclosed with tall adobe walls for privacy.

But the centerpiece of such larger homes was the zaguán, wide and tall enough to accommodate teams of draft animals and a coach or light wagon, which not only functioned as a reception hall and focal point of the residence, but could also double as an outdoor dining area. Sturdy tandem doors constructed with heavy, rough-sawn pine planks could be barred from the inside to secure the entrance. The rest of the home was arranged, spoke-like, around the hub of the zaguán. More public rooms, like the sala, or parlor, and the comedor, or dining room, often fronted the street. Bedrooms were usually placed toward the interior of the structure for privacy. The cocina, or kitchen, was, of course, adjacent to the comedor, with the stove installed on a rear exterior wall for exhaust and heat venting, and a dome-shaped oven was located outside to keep heat out of the house and minimize the risk of fire destroying the building. Finally, the corredor, covered with an earthen roof, provided shade between the kitchen and the central patio, and a place to prepare food in the open air, away from the heat of the stove.[iii]

Carpenter H. J. Olds died of consumption at Cerro Colorado late in the morning on October 27 — the first death at the Heintzelman mine, and one the settlers might later regard as blissfully mundane. He was buried at sundown, and although Heintzelman and mining engineer Frederick Brunckow searched through his personal effects, and determined Olds had a brother in California and a sister and other family in Wisconsin, they found no specific information that would have made it possible to notify kin of his death. A week later, Olds’s personal property, including a horse and saddle, were sold at auction for forty dollars. And also in the fall of 1858, William Kirkland was robbed of some oxen and blankets at the pinery in the Santa Rita Mountains by thirty Apaches. The Pima and Maricopa lost a headman and two others in a fight with Apaches near the mouth of the San Pedro River at the Gila, but killed seven of their enemy. Afterward, they visited Fort Buchanan to request more arms and ammunition.[iv]

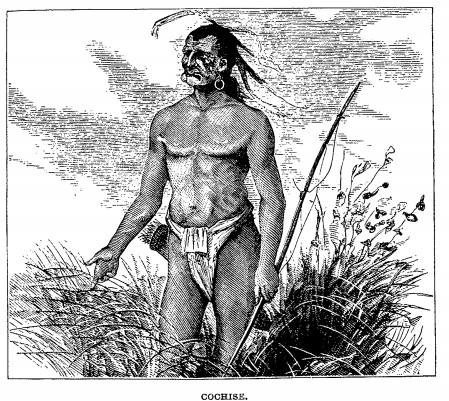

It was around this time that an Apache headman began making tentative peaceful gestures toward Americans at the Apache Pass stage station, more than a hundred miles northeast of Tubac. After Miguel Narbona’s death a few years earlier, and the death of Carro — from poisoned rations issued at Janos Presidio in Chihuahua the previous fall — he had become one of the leading headmen of his band of the Chiricahuas. His name was Cochise, and his band favored Stein’s Peak, Apache Pass, and the Dragoon Mountains for their encampments. It is likely that Chiricahua Apaches had been involved in at least some of the assaults on settlers and travelers south of Tucson, the kind of attacks Phocion Way and the Hispanic laborers at the Santa Rita mining camp feared. Cochise researcher Edwin Sweeney speculates that the swelling ranks of Americans — soldiers at Fort Buchanan; miners in Tubac, Sopori, Arivaca, and the Santa Ritas; and stage personnel along the Butterfield Overland Mail route, as well as a strengthening of military forces in Sonora — may have forced Cochise’s attempt at rapprochement.[v]

Samuel Cozzens, the Mesilla attorney, claims to have met Cochise, whom he described as wearing only a breechcloth and moccasins:

“He was a tall, dignified-looking Indian, about forty-seven years of age, with face well daubed with vermilion and ochre. From his nose hung pendent a ring about five inches in circumference, made of heavy brass wire, while three of the same kind dangled from each ear. His body had been thoroughly anointed with some kind of rancid grease, which smelled very offensively. His stiff black hair was pushed back and gathered in a kind of knot on the top of his head, while behind it rested on his shoulders. One or two eagle feathers were fastened to his head in an upright position, and swayed with every breath of wind. As he came near me, he laid his bow and arrow down upon the grass, and extended an exceedingly dirty hand, with finger-nails fully an inch in length, saying, in pretty fair Spanish, — ‘Me Cochise, white man’s friend. Give me bacca.’”[vi]

Cochise had a quite different meeting with an American when forty-year-old Indian Agent Michael Steck arrived at Apache Pass at the end of December 1858 and issued “presents” — including cattle, twenty fanegas of corn, 211 blankets, one hundred yards of manta, and two hundred brass kettles — to nearly six hundred Chiricahuas represented by the headmen Esquinaline, Cochise, and Francisco. Men of fighting age were underrepresented during the issue, though, as one group was out raiding in Sonora, and would return within a week with fifty mules and two female captives, and a second party was off with Mangas Coloradas’s Mimbres Apaches on a separate raid, according to the Missouri Republican. Cochise nearly missed the largesse himself, as he had been in Sonora with Mangas Coloradas, but returned by Christmas, several days before the rations were issued.

After the distribution of gifts to the Chiricahuas, Steck was visited in his Apache Pass camp by about forty Coyotero men who were en route to Mexico for still another raid. The agent managed to convince the Coyoteros to abandon their plan and meet him again at Santo Domingo Springs, some seventy-five miles northeast of Fort Buchanan, to receive their own issue of presents and have a discussion on January 22, 1859. On that date, one hundred and seventy White Mountain Coyotero men assembled some two miles from Steck’s camp, and marched to the meeting in double file, making quite an impression. Yet twice as many White Mountain Apache warriors had remained in their Mogollon Rim homeland to defend against raids by the Navajo. After an introductory speech, in which Steck praised the Coyoteros for keeping peace with the Americans, and announced that the presents about to be distributed were their reward for behaving well, a White Mountain captain rose to speak. He complained that the White Mountain Apaches had suffered greatly from the soldiers’ destruction of their crops during the Gila Campaign, and had been too discouraged to replant the following year, out of concern that their work might again be destroyed. Regardless of how Steck may have felt regarding their losses, he had to know their raiding bands were responsible for depredations against American settlers and travelers along with the Pinals’, Tontos’, and Chiricahuas’ bands. Whether Bonneville’s punishing campaign was an effective strategy for reigning in the raiders remained to be seen.

In what must have been a discouraging sign for both the army and the Indian agent, within a week of receiving their presents at Apache Pass, Chiricahuas again stole horses from a settlement on Sonoita Creek. Ewell and Steck received the bad news when they returned to Fort Buchanan after the Santo Domingo Springs meeting with the Coyoteros, and another with the Pinals, in which more rations were issued. The men returned to Apache Pass to discuss the Sonoita Creek raid with the Chiricahua headmen, and tried to convey to them that raids directed against Americans were unacceptable and would bring consequences. The headmen appeared to understand, and not only returned the stolen horses but released a fourteen-year-old girl, recently captured on one of the raids into Sonora, as proof of their sincerity, and the Americans arranged for the girl to be returned to her parents through the Prefect of San Ignacio. Also in January, troops out of Fort Buchanan discovered Apache raiders with stolen stock at Dragoon Springs and engaged them, killing six or seven and recovering forty head of the animals.

Homegrown thieves weren’t safe from continuing Apache depredations: after Hispanic employees of the Santa Rita Exploring and Mining Company absconded with nine mules and five horses at Apache Pass, they were robbed of their plunder by Apaches near the Santa Rita del Cobre mines, at Pinos Altos by the headwaters of the Gila. The raiders ate the twice-stolen mules and, in a politically expedient gesture, turned three horses over to Agent Steck as proof of their cooperation. But their gesture didn’t gain them much favor: when word of it reached Santa Rita Company agent William Wrightson, he wrote Steck to demand the return of the surviving horses, $1,492 in compensation for the mules the Apaches had eaten, and the saddles, shotguns, and other hardware they had bartered away or still held. It was unclear whether the livestock had been taken en lieu of wages, or was simple theft.[vii]

On March 3, 1859, editor/writer Edward Cross launched the Weekly Arizonian in Tubac. In that first edition he listed twenty incidents of Apache raiding in or near the Santa Cruz Valley during the first two months of 1859, in which two cattle herds, a mule train, and more than one hundred other animals were taken and three men murdered. Two of the raids were on Fort Buchanan stock. Sonoita innkeeper James “Paddy” Graydon caught a Fort Buchanan deserter named Bentley as he attempted to steal horses from Fort Buchanan’s corral in February. Two years gone from his post, Bentley had been living in Hermosillo, and was suspected of a number of horse thefts in the Santa Cruz Valley. He was turned over to the army and placed in the stockade — escaping a horse-thief’s usual fate of hanging due to the lack of a court to try him.

Two incidents of Mexicans stealing horses were reported, as was the killing of a cow belonging to William Wordsworth and the flight of would-be raiders from Bill Ake’s property when they were met by gunfire. Ann Maria Ake married Bill Ake’s close friend George P. Davis. Edward Cross complained that the Territory of New Mexico’s seat of government was so distant bad characters were operating with impunity on the Santa Cruz. The government denied Arizona separate territorial status, delayed the establishment of mail routes, and failed to adequately protect settlers against Indian depredations, Cross protested, yet managed to establish custom houses and exact a usurious tax on goods imported from Sonora, “a principle adverse to the fundamental doctrines of a Democratic government.” And he complained that Company D First Dragoons under Lt. Lord would soon be reassigned to Fort Fillmore, leaving Fort Buchanan without a mounted force, making matters even worse. All the same, Paddy Graydon bravely announced the opening of the United States Boundary Hotel on the Sonoita Valley road, three miles from Fort Buchanan, promising “a fine assortment of wines, liquors, cigars, sardines, etc.” and insurance on horses left in his establishment’s care.[viii]

Eleven days after Indian Agent Steck issued new rations at Apache Pass, a resident who signed himself “H. T.”, likely Butterfield Agent James H. Tevis, wrote the Arizonian to complain that Chiricahuas there had already converted much of the corn Steck had issued them into tizwin, a crude but popular alcoholic beverage among the Apache. The Chiricahuas were planning a raid on Fronteras, but decided to postpone it until they finished all the tizwin. “Since that time they have carried on high;” wrote H. T., “both day and night they are passing our house whooping and yelling, and there has not been a day since the Frontera[s] bill was postponed that we have not had trouble with them . . . When any government train is here they are as gentle as lambs, but as soon as the train leaves, the devil seems let loose among them.” H. T. recommended that Steck issue smaller rations of corn. “As it is now, they only make one meal out of a sack, and put the rest soaking for liquor.”[ix]

Late in spring 1859, labor relations were strained when Reventon Ranch manager George Mercer disciplined seven Mexican workers for an unknown infraction, whipping them and cropping their hair so closely that some called it scalping. In a defense published in the Weekly Arizonian, Mercer complained the claim of scalping was a lie promulgated by “the white Greaser association,” and defiantly wrote “The men were whipped and their hair cut off, but nothing more; and I here state that I am responsible for the act, and whoever does not approve of it, can apply and obtain satisfaction from the undersigned.”[x]

A few days later, near Tumacácori, two Mexican ranch hands crept into the room of their sleeping supervisor, Greenbury Byrd, struck him in the head with an ax, and fled to Sonora with his livestock. He was found about three o’clock in the afternoon and given what medical care could be provided, but died that night. While the Arizonian described Byrd as “a quiet, good-natured, respectable young man,” who treated his men kindly, Solomon Warner would later declare that Byrd had led a gang of thugs who tried to shake down Edward Miles for $1,600 after he was shot in the chest by a servant the previous year, and when Miles was moved to the infirmary at Fort Buchanan for better care, Byrd’s gang had looted his Tucson store and stolen most of his livestock. Others reported Byrd had been present for Mercer’s whipping of the Reventon laborers, and claimed he had failed to pay his own migrant employees. Defenders countered the latter by claiming another ranch employee was in Tucson attempting to secure currency to pay them at the time of the assault.[xi]

Filibusters John Page, Bill Ake, and Alfred Scott, along with Sam Anderson, men named Brown and Bolt, and Elias Pennington’s eighteen-year-old son Jack, swept up the Sonoita Valley two days after Byrd’s murder, apparently bent on revenge, methodically chasing all Mexicans in the area toward Fort Buchanan at gunpoint. Intimidation turned to murder when the regulators reached Mescal Ranch on the upper creek: there they fired their weapons on fleeing Mexican and Yaqui distillery workers when they ignored orders to halt, killing four outright and leaving a fifth with five bullet wounds and a shattered ankle. One of the filibusters was slightly wounded as well, when a distillery worker lanced him in defense. Curiously, Reventon Ranch manager George Mercer — who, it could be argued, had set the whole chain of events in motion with his demeaning treatment of Mexican ranch hands — was at the distillery at the time.[xii]

Response to the regulators’ assault was immediate and direct: migrant workers in mines and farm camps all along the Santa Cruz fled to Sonora, leaving the Cerro Colorado and Patagonia mines deserted — effectively shutting down operations at those sites — and many farms without workers to seed the coming season’s corn crop. The settlers’ primary source of labor vanished overnight, “a disasterous event to the entire country,” lamented Edward Cross. But the settlers’ response was equally clear. While there is little doubt they were disturbed by the grisly murder of Byrd, they seem to have been more angered by the regulators’ killing of blameless distillery workers, and their community’s reduction to the kind of anarchy and vigilante justice Charles Poston had warned of in his letters to Sylvester Mowry two years earlier.[xiii]

The killers were roundly denounced in public meetings in Tubac and Tucson. Within a week, Captain Isaac Reeve dispatched sixteen dragoons from Fort Buchanan to accompany affected farmers B. C. Marshall and Paddy Graydon, and a Mr. Hall, in tracking down the Sonoita Valley murderers. The party was well received in Tucson, where one of the Oury brothers supplied fresh horses, and word quickly passed to Butterfield Overland Mail Company staff to keep an eye out for the fugitives. Page, Bolt, Scott, and Anderson were quickly apprehended and placed in chains at Fort Buchanan. But the search continued for Bill Ake — for whom a hundred-dollar reward was offered; Brown — who had gravely wounded the fifth distillery worker, now under the care of Assistant Surgeon Irwin at the fort; and young Jack Pennington — who, it was somehow decided, had not directly participated in the murders.[xiv]

The Santa Rita Company’s Herman Ehrenberg wrote letters to influential Sonorans Miguel Zepeda, Joaquín Pompa, and Prefect José Morena in Altar; José Elías in San Ignacio; and Commissioner José Islas in the colony in Saric; describing the American settlers’ outrage over the murder of the distillery workers, and reporting the aggressive steps being taken to bring the killers to justice. And Ehrenberg publicly suggested the Sonorans might be more helpful if Americans kept the filibusters under control: “In reference to the prevention of horse stealing and other crimes, a hearty cooperation is promised by the [Sonoran] authorities and the hope is expressed that our citizens will assist in bringing to justice all persons connected with such acts.” [xv]

Six weeks after the loss of all the Patagonia Mine’s barreteros and tenateros in early May 1859, Apaches captured all the operation’s mules. A California congressman who had killed a waiter at Willard’s Hotel in Washington, D. C. decided Tucson’s arid, sunny climate might be beneficial to his health, and joined the ranks of fugitives. Frustrated that Mesilla had failed to provide them with any semblance of local government, and seemed more concerned with collecting taxes and addressing the needs of Indians, rather than settlers, fifty-six Americans in Tucson held an ad hoc election, and decided on J. W. Holt for Justice of the Peace and George Mattison for constable. But regardless of ax murders, vigilante revenge, Apache raids, a continuing influx of outlaws, and the struggle for civil order in the first half of 1859, San Juan’s Day was celebrated in Tucson with the usual enthusiasm on Friday, June 24. For many, the morning horse race between a Mexican steed and one from California was the favored event of the celebration. Unfortunately, the Californian won by half a length and “considerable money changed hands on the result, greatly to the disappointment of the Mexicans,” who had been confidently looking forward to a victory celebration. Next on the program were cockfights, organized by the Hispanics, followed by a succession of American “free fights” — interrupted by a short intermission, during which injuries were treated and more alcohol was consumed — for the remainder of the day. “It is almost miraculous that half a dozen people were not killed,” remarked Edward Cross in the Weekly Arizonian, “considering the freedom with which revolvers were flourished about.” The evening ushered in a grand promenade of Hispanic couples on the best horse, mule, or donkey they could muster for the event.[xvi]

The evening after the celebration, some Hispanic men traveled the road between Tumacácori and Tubac, shouting and laughing loudly as they walked. Alarmed by the raucous strangers, dogs belonging to two Americans who lived along the road began to bark, and the Hispanic men drew knives and chased after them. John Ware and James Carothers left their house and approached to try and calm the situation, but Ware was grabbed by Rafael Polanco and thrown to the ground, prompting Carothers to run to the house for a shotgun. While Polanco held Ware down, the other men stabbed him five times; Carothers returned and began shooting, hitting one of the assailants named Cruz. Although seriously wounded, Ware managed to partially raise himself, draw his revolver, and fire several rounds at the retreating assailants. But his lungs had been punctured in two places and, despite the life-saving efforts of physician C. B. Hughes, he would die within twenty-four hours. John Ware had first arrived in the Far Southwest in 1842, before the Mexican-American War, when Arizona was still Sonoran frontier. He’d worked a farm near Tubac with Carothers for several years and, according to Edward Cross, was regarded a “brave, generous, honest man, abounding in social qualities, hospitable and kind.” He was laid to rest in the old churchyard in Tubac, survived by two brothers — one a purser in the navy and the other a bank teller in Richmond, Virginia.[xvii]

Ware’s murder presented a dilemma for the still-nascent American community on the Santa Cruz: while they had a military outpost and a customs house, they, like the Tucson settlers, still had no local institutions to deal with crime — so they, too, cobbled together an impromptu civil authority. A “party of citizens” proceeded to arrest Rafael Polanco, the only assailant Carothers had been able to detain, the morning following Ware’s death, and brought him before a meeting of citizens in Tubac the following afternoon. Chairman Edward Cross and Secretary C. B. Hughes, the physician who had attended Mr. Ware, reviewed what the citizens present considered to be the facts surrounding Ware’s murder, “and furthermore, that the prisoner was a thief.” Santa Rita Company executive S. H. Lathrop offered resolutions which included a statement regarding Mr. Ware’s murder, a request that the commanding officer of Fort Buchanan hold the prisoner until he could be sent to Mesilla for trial, and another request that the Judge of the Rio Grande District make arrangements to hold a court in the settlers’ section of the Territory. Following some discussion, the resolutions were carried. The group then moved and unanimously adopted a further resolution: “[I]n the future, until the establishment of law and courts among us, we will organize temporary courts, and administer justice to murderers, horse thieves, and other criminals, ourselves.”[xviii]

As the meeting adjourned, some present thought it advisable to elect some civil officers to carry out the new procedures — that is, to pair a law enforcement component with the criminal justice structure they had just improvised, so a second meeting was organized with Lathrop as Chairman. The group in the second meeting decided to elect a Justice of the Peace and a Constable, as had Tucson. James Carothers, who had shared a house and farm with the murdered man, and had run to his defense with a shotgun, was nominated for Justice of the Peace; Solo Warner’s teamster Nelson Van Alstine, who had shot Cotton for annoying him ten months earlier, was nominated for Constable. Voters from the Sonoita Valley, Santa Rita, Sopori, and Reventon elected both candidates without opposition, casting thirty-one votes for each. The second committee then promptly tried its first case, that of a Hispanic charged with stealing from N. B. Appel: “The theft being proved,” reported Edward Cross, “the prisoner was sentenced to receive 15 lashes, which were duly administered by the new constable in a prompt and effective manner.”[xix]

Not to be outdone by the Tucson and Santa Cruz settlers’ progress in establishing criminal justice, the army held a court martial at Fort Buchanan that same week, convicting Alenson Bentley of desertion and horse thievery, and sentencing him to have his head shaved, receive fifty lashes “with cowhide, well laid on the bare back,” serve six months hard labor in irons, forfeit his pay, and be branded with the letter “D” by a red-hot iron and drummed out of the service with a dishonorable discharge. (This is likely the same Bentley Paddy Graydon had caught trying to steal horses at Fort Buchanan a few months earlier, and recently tracked down in Sonora after his second escape from the stockade.) Privates Rice, Donovan, and Young were also convicted, and sentenced to be whipped and drummed out of military service, but the court and Col. Bonneville may have decided they’d made their point with the rather severe sentence of Bentley, as they “remitted” the other men’s sentences and restored them to military service. While at new Fort Buchanan, Bonneville inspected the soldiers quarters, mere ”Jacals built of upright poles daubed with mud,” and storehouses, temporary sheds covered with tarpaulins, concluding that the post would have to be rebuilt, and again complaining about its location.[xx]

A week after the San Juan’s Day celebration and John Ware’s murder, a letter from Tucson appeared in San Francisco’s Daily Alta California. The anonymous correspondent declared there was long-standing hostility between Hispanics and Americans on the Santa Cruz, and that enmity had intensified lately. Murders and assassinations between the races, the writer claimed, were commonplace. A second anonymous report suggested the situation threatened to erupt into a “war of races.” But these claims seem hyperbolic given the strong public defense of the assaulted laborers and distillery workers. The knowledge that mining and farming and the distilling of mescal couldn’t take place without them certainly earned the migrants support, but the breadth and tone of the response to their assault seems more than self-interest. It’s possible the letters to the Daily Alta California were written by Edward Cross — although others shared the writer’s pessimism and alarm.

Accommodating the complex O’odham – Mexican – manso Apache economy and social structure was difficult for Americans. Two distinct streams of culture engaging and jostling one another was challenging enough, but the problems caused by raiding and filibustering compounded the difficulty. Still, another dynamic managed to work its way into the equation. The second report from the Santa Cruz Valley to San Francisco claimed Americans not only ignored Apache raids into Sonora, but abetted them. A military officer had recently made an agreement with one band to turn a blind eye to their excursions below the boundary line, the correspondent claimed, if they would refrain from stealing and murdering on the American side. “This has greatly exasperated the good and influential citizens of Sonora,” he wrote, “and they therefore make little or no exertion to arrest persons who have committed murders or robberies in Arizona,” such as the killers of Greenbury Byrd, and the Butterfield carpenters at Dragoon Springs. The writer of the second Daily Alta California report from the Santa Cruz complained, “[A]s we have no laws or officers of justice, our social condition is not a very happy one.”[xxi]

On June 19, the Mescal Ranch distillery worker who had been shot five times by the regulators had his shattered leg amputated. A few days later, local barrister Samuel Cozzens filed a writ of habeas corpus in Mesilla on behalf of the Sonoita Valley murderers, as they had come to be known. Remarkably, it then became the responsibility of Prefect Raphael Ruelas to hold a preliminary hearing to determine whether there was sufficient cause to bring the case to trial. This development did not bode well for the victims of their crime, or the rule of law on the Santa Cruz. Despite the well-reasoned requests of Indian Agent Michael Steck, Ruelas had not brought the Mesilla Guard to justice for the cold-blooded murder of at least fifteen peaceful Apaches in two separate incidents the previous year. And Ruelas once again showed more empathy for vigilantes than for their victims. The case against the Sonoita Valley murderers never made it to trial. On July 6, Ruelas fined them nine hundred dollars; they paid one hundred on account, and were released.

John Page and Alf Scott returned to the pinery in the Santa Rita Mountains, and Jack Pennington found work as a cowhand with William Wadsworth back on the Sonoita. Bill Ake had eluded capture and fled the Gadsden Purchase prior to Ruelas’s preliminary hearing. The army, at least, decided it had seen enough: the filibusters and their ilk were told they were no longer welcome at Fort Buchanan.[xxii]

When Page, Scott, and Jack Pennington first returned from court in Mesilla, Cochise saw opportunity in the political chaos of Sonora and raided Fronteras. Noting that the Santa Rita Mining Company had restocked after their previous raid, Parte — headman of another band of Chiricahuas — led a coalition of several bands in the theft of another eighty to ninety horses and mules from the company’s Patagonia site. According to the captive Merejildo Grijalva, some men from Cochise’s band had participated in the raid, and when they returned to his camp with some of the livestock, Cochise demanded they return the animals to the company. One raider balked at Cochise’s demand, reports Grijalva, and Cochise lanced him in the heart, killing him. Cochise then seized eleven animals and ordered two of his men to return them to Fort Buchanan, which they did on July 21. But it remains to be seen whether such demonstrations of influence over his band and acquiescence by Cochise were genuine, or merely for show. Some, like James Tevis, Butterfield station agent at Apache Pass, weren’t impressed: “For eight months I have watched him,” Tevis declared, “and have come to the conclusion that he is the biggest liar in the Territory! and would kill any American for any trifle, provided he thought it wouldn’t be found out.” Members of Cochise’s band stole another twenty-four animals from the Sonora Company’s Arivaca mine in July, and hit the beleaguered Santa Rita Company’s Patagonia mine yet again for a paltry five animals, demonstrating that the government’s policy issuing of “presents” to the Chiricahua had not bought settlers much security.[xxiii]

One incident that appears to have angered Cochise was the killing of a raider from his band, likely by Bill Ake and his fellow filibuster George “Sugar” Davis, when some Chiricahuas attempted to steal a horse near Patagonia. James Tevis claims Cochise was so enraged over the incident that he requested a war council, and threatened to cut off American access to the springs at Apache Pass. According to Tevis, Esquinaline, a cooler head, wryly commented at the time, “I think it is a big pile of corn in the station, more than revenge, that Cochise wants,” and argued before the council that the Americans would treat them well if not molested. Esquinaline reminded them that Americans had given corn to their families in winter when food was scarce and their men were out raiding in Mexico, spoke out clearly against war, and arranged a meeting between Cochise and Tevis. In that meeting, Cochise demanded to know why the Apache had been killed; Tevis claims to have told him bluntly “all Americans look upon a thief as a fit subject to be killed at any time.” Cochise stubbornly insisted his men had never stolen property from Americans. Tevis countered that Cochise himself had been seen riding his dun-colored horse when Chiricahuas stole American stock at Babocomari. Tevis’s own stock had been taken in that raid, he argued, and when he later refused an invitation to dine with Cochise, it had been because he didn’t want to eat his own mules. “You also drove off the Santa Rita Mining Company mules,” he claims to have told the headman, “and a third or a fourth of them are in your camp at this time.”[xxiv]

While many of the raids against Americans were conducted by

Pinal, Tonto, and Mimbres Apaches, the proximity of Chiricahua camps to Apache

Pass, the overland mail road, and the Santa Cruz Valley made the largest

settlements convenient prizes for Cochise’s tribe. Cochise had only recently

become a headman in his unruly Chokonen band, and was still working to

establish his authority. Yet his duplicity in his dealings with Americans was,

by late summer 1859, unmistakable. He had returned from a raid on Sonora the

previous Christmas in time to accept “presents” Indian Agent Steck offered as

an enticement not to raid Americans. But within a week, Chiricahuas stole

horses on Sonoita Creek. After a conciliatory talk with Steck and Ewell

following that theft, troops from Fort Buchanan encountered Apaches with stolen

stock at Dragoon Springs. In Mid-June, Apaches stole all of the mules from the

Patagonia mine. After mine managers had replenished the stock, a coalition of

raiders from several Chiricahua bands, led by the headman Parte, stole another

eighty to ninety horses and mules from the same site. Then Cochise’s Chokonen

stole twenty-four animals from the Arivaca mine, and hit the Patagonia mine a

third time. After stealing stock from Samuel Cozzens at Apache Pass, Cochise

sold Cozzens stock stolen from another stage station north of Tucson. And then,

if Cozzens is to be believed, Apaches preying on the road between Apache Pass

and Tucson robbed the Frazier family, brutally killing Mr. Frazier and his

eldest son, and either seizing Mrs. Frazier and their three other children as

slaves or killing them as well. While we have one recorded instance, after

Parte’s raid on the Patagonia mine, in which Tevis describes Cochise

dramatically exercising control over members of his band, the fact that some

from his band felt free to join Parte, rather than raid in Sonora with him,

suggests that Cochise’s authority was tenuous.[xxv]

self-portrait, John Ross Browne, Adventures in the Apache Country: a Tour through Arizona and Sonora, with Notes on the Silver Regions of Nevada (New York: Harper & Brothers, Publishers, 1869), 126.

Enter raiders’ mayhem to continue.

[i] John Butterfield signed a contract with the government to provide mail service from St. Louis, Missouri to San Francisco on September 11, 1857. Eastbound Butterfield coaches had already passed through Tucson by October 2, 1858. Thomas H. Peterson, Jr., “The Buckley House: Tucson Station for the Butterfield Overland Mail,” Journal of Arizona History 7, no. 4 (Winter, 1966): 153-55&nn2-3, 156n7. Although already widowed, Guadalupe Santa Cruz was only forty-four years old in 1858. Census for the First Judicial District (1864), Arizona Territory, 1; enumerated in April 1864.

[ii] Peterson, 155-59, 156n7.

[iii] Historic Preservation Consultants and David C. Mackie, Historic Architecture in Tucson: A Report by Historic Preservation Consultants (Tucson: The Consultants, 1969), 20-21, 25, 190-93, 196, 205-206, 209, 253-58; illustration “Typical Tucson Home;” figures 8, 11, 170, 171, 195, 205.

[iv] Diane M. T. North, ed. Samuel Peter Heintzelman and the Sonora Exploring and Mining Company (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1980), 110, 112, 113, 120, 124.

[v] Edwin R. Sweeney, “Cochise and the Prelude to the Bascom Affair,” New Mexico Historical Review 64, no. 4 (October 1989): 428-30. Cochise scholar Sweeney identifies Cochise’s band as the Chokonen. C. D. Poston, “The Story of Marajildo and Rosa,” Tucson Weekly Star, October 7, 1880. A typescript copy found in Merejildo Grijalva, Hayden biographical file, AHS. Grijalva would come to be known as Mickey Free.

[vi] Samuel Woodworth Cozzens, The Marvelous Country . . . (1873; reprint, Secaucus: Castle, 1988), 86.

[vii] Twenty Mexican fanegas of cob corn would have weighed around 3,600 pounds. Sweeney, “Cochise and the Prelude to the Bascom Affair,” 429-32, 432n12. Michael Steck to Col. James L. Collins, Superintendent of Indian Affairs, Apache Agency (Santa Barbara), New Mexico Ty., February 1, 1859; John Walker, Indian Agent at Tucson, to Michael Steck, Tucson, January 3, 1859; William Wrightson, Agent for the Santa Rita Exploring and Mining Company, to Michael Steck, Tubac, March 10, 1859; all in the Michael Steck Papers, CSWR MSS 134 BC, Box 1, folder 9, RMOA, CSWR, University Libraries, University of New Mexico.

[viii] Weekly Arizonian, March 3, 1859. Both editor/writer Cross and the printing press on which the Weekly Arizonian would be composed likely arrived with William Wrightson’s train on January 3. James H. Tevis, Arizona in the ‘50’s (Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press, 1954), 97-98. Tevis also tells the tale of a deserter who sounds very much like Bentley (64-69). Constance Wynn Altshuler, ed. Latest from Arizona: The Hesperian Letters, 1859-1861 (Tucson: Arizona Pioneers’ Historical Society, 1969), 7. Phocion R. Way, “Overland by ‘Jackass Mail’ in 1858,” part 3, ed. William A. Duffen, Arizona and the West 2, no. 3 (Autumn, 1960), 281n6. North, Samuel Peter Heintzelman, xii.

[ix] Weekly Arizonian, April 21, 1859.

[x] I. V. D. Reeve to J. D. Wilkins, Acting Assistant Adjutant General, Fort Buchanan, New Mexico [Territory], May 20, 1859. Weekly Arizonian, May 19, 1859 (quote). Roberts dates the incident at George Mercer’s Reventon farm “a few days earlier” than the Greenbury Byrd murder on May 6. Virginia Culin Roberts, With Their Own Blood: a Saga of Southwestern Pioneers (Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press, 1992), 67.

[xi] Weekly Arizonian, May 12, 1859. Solo [Solomon] Warner, “To the People of Arizona: The Testimony of an Old Citizen on Hon. Granville H. Oury.” In Cornelius C. Smith, Jr., “The History of the Oury Family,” 85-86. Cornelius C. Smith, Jr. Papers, MS 738, B1, f10, AHS. Cornelius C. Smith, Jr., William Sanders Oury, 98-99. Benjamin Harbaugh Miles, biographical file M 643B-2, AHS. Greenbury Byrd, Hayden biographical file, AHS.

[xii] Weekly Arizonian, May 19, 1859. Sacramento Union, May 25, 1859. I. V. D. Reeve to J. D. Wilkins, Fort Buchanan, May 20, 1859. Roberts, With Their Own Blood, xv, 66-71.

[xiii] Weekly Arizonian, May 19, 1859. Sacramento Union, May 25, 1859. Charles D. Poston to Lt. Sylvester Mowry, [no location], August 5, [1857]; Tubac, August 15, 1857. In Sylvester Mowry, Memoir of the Proposed Territory of Arizona (Washington: Henry Polkinhorn, Printer, 1857), 20-23.

[xiv] Weekly Arizonian, May 19 and 26, 1859.

[xv] Weekly Arizonian, June 2, 1859 (quote).

[xvi] Daily Alta California, July 8, 1859. The territorial government had assigned a customs officer to collect a 20 percent import duty at Calabasas by August 1857, and an Indian agent in Tucson within another year, but no personnel to mediate criminal justice. Poston to Mowry, August 5, [1857]. In Mowry, Memoir, 22-23. The earliest mention of Indian Agent John Walker located is in Samuel Heintzelman’s journal entry for August 16, 1858. North, Samuel Peter Heintzelman, 54. Weekly Arizonian, May 5, June 30, 1859.

[xvii] Weekly Arizonian, June 30, 1859.

[xviii] Weekly Arizonian, June 30, 1859.

[xix] Weekly Arizonian, June 30, 1859.

[xx] Constance Wynn Altshuler, Chains of Command: Arizona and the Army, 1856-1875 (Tucson: Arizona Historical Society, 1981), 7. Two weeks after he was caught stealing horses at Fort Buchanan by Paddy Graydon, Bentley somehow got hold of a metal file and removed his shackles. Given permission to approach the door of the stockade, he kicked off the restraints and fled. The sentry fired a shot after him, but missed, and Bentley rounded a corner and ran straight into a sergeant. He was returned to the stockade and fitted with stronger irons, but succeeded in a second escape the first week of June. He made it to Sonora before Paddy Graydon and four others from the post recaptured him. It wasn’t “strictly lawful” to pursue horse thieves across the boundary line, wrote Edward Cross in the Arizonian, but the public benefit probably justified the infraction. Weekly Arizonian, March 17, May 5, June 30, 1859. Tevis describes an individual quite similar to Bentley (64-67).

[xxi] Daily Alta California, July 15, 22, 1859.

[xxii] Weekly Arizonian, June 23, 1859. Roberts, With Their Own Blood, 75-76, 99. James B. O’Neil, They Die But Once, The Story of a Tejano (New York: Knight Publications, Inc., 1935), 30-31. Cozzens, it turns out, was familiar with criminal defense strategies, and befriended murderer and San Francisco fugitive Ned McGowan. Bill Ake was back on the Santa Cruz in time to be counted for the 1860 census on August 2, when he was listed as living with seventeen-year-old Elisa Ake, nee Lizzie Bacon, in Tucson, a farmer with $2,500 in personal wealth. Decennial U.S. Census (1860), County of Arizona, New Mexico Territory; Tucson Division, 9; enumerated on August 2, 1860.

[xxiii] Sweeney, “Cochise and the Prelude to the Bascom Affair,” 435-37, 435n19, 436nn21-22, 437. Tevis, 52. Weekly Arizonian, July 14, 1859 (Tevis quote).

[xxiv] Tevis, 138-40, (quotes 139-40). Sweeney, “Cochise and the Prelude to the Bascom Affair,” 438. Ake had also driven off Apaches near his property with gunfire on February 21, after a cow belonging to William Wordsworth was killed on Sonoita Creek. The Weekly Arizonan, March 3, 1859. Cozzens reports a man named Bill May, who lived on the Santa Cruz, boasted of killing two Apaches as well (163).

[xxv] Merejildo Grijalva, Hayden biographical file, AHS, 2. Edwin R. Sweeney, Cochise, Chiricahua Apache Chief (Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1991), 5, 118. Sweeney, “Cochise and the Prelude to the Bascom Affair,” 437. Grijalva was kidnapped by Apaches as a child, and refers to captives as slaves. Slaves usually hauled water and wood in encampments, and were often ransomed back to their families, or were sold or bartered for goods such as livestock, clothing, firearms, and gunpowder. In some of their campaigns, Hispanic dragoons seized surviving Apache women and children as slaves. Gila River Pimas sold Apache, Yavapai, and Quechan slaves at the presidios. The priests and friars seem only to have been concerned that the captives be treated humanely, and that they receive religious instruction. Diego Miguel Bringas de Manzaneda y Encinas, a Franciscan administrator from the College of Querétaro complained, however, when an official from Arizpe took ten Apache slaves from a Pima without compensation. He worried the loss might encourage the Pima to simply execute all captives in the future. James E. Officer, Hispanic Arizona, 1536-1856 (Tucson: University of Arizona Press, 1987), 76.